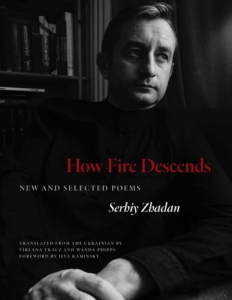

Serhiy Zhadan: How Fire Descends

HOW FIRE DESCENDS: NEW AND SELECTED POEMS, Serhiy Zhadan. Translated by Virlana Tkacz and Wanda  Phipps, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2023, 136 pages, paper, $18, yalebooks.yale.edu.

Phipps, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2023, 136 pages, paper, $18, yalebooks.yale.edu.

I purchased this book last April, but have put off blogging about it because I would love to attempt to do it justice. A beautiful book, moving poems, by a poet — musician, activist, Ukrainian soldier — I admire so much.

My home life has been challenging of late, a husband’s illness, and so forth, but I read poets such as Zhadan and think, surely I have no excuse not to write.

So, here, just one poem from the book, and my highest recommendation.

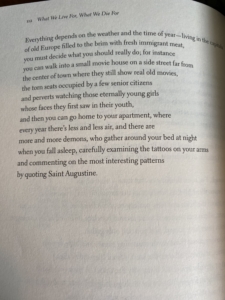

“Remember Every Building”

Remember every building and every street, you tell me.

Remember everything that disappears like a traveler descending a hill.

Saying it out loud will drive away the silence and ward off trouble.

Just try to remember this light which pierces the apartments and roofs through and through.

Right now — when there is no turning back from September.

Right now — when we embrace as if we were at the wedding of other people’s children.

Remember these figures in the streets, refined by exhaustion and love.

Remember the ability of birds to come together in the autumn air,

the ability to absorb a person’s fear and warmth, hidden under their shirt,

the joy of recognizing who is on your side by a slight turn of the head.

Despite the wind, remember the breath, the presence, the eruption of language.

As you choose your words: just try to remember this month,

which changes everything, these trees, growing like children, easily growing into maturity.

September 11, 2022

— Serhiy Zhadan

I took a photo of the poem because I am certain the long lines will not translate onto your screen:

In the foreword, Ilya Kaminsky calls Zhadan “the most beloved Ukrainian poet of his generation.” After outlining the poet’s experiences previous to and throughout the current on-going war with Putin’s Russia, Kaminsky adds:

But Zhadan’s writing also manages to transcend his own landscape through his exploration of the dualities and connections between seemingly unlike things. For years he has sought to define the mysterious relationship between war and language. He is a public person who seeks to render visible the most intimate experiences of lovers, knowing all too well that “a language disappears when no one speaks of love.” He is a symbol of his country’s hope and resistance… (p. xii)

I wrote about Zhadan in April of 2023, and you’ll find a bunch of interesting links to follow there.

borrowed from gettyimages