from pexels.com

I have been working on a book–and because I ground to a halt WITHOUT FINISHING my last major project–it’s no surprise that I haven’t been able to find the confidence to step back and declare this book “done.”

Additionally, I should admit that summer is always my toughest season for writing. I tend to forget this, and I forget that I need to be gentle with myself in the summer when my family is all at home and various people expect me to hang out with them in the sunshine. Even so, because of my blog class, I decided to email a few bloggers, and quite a few of my friends–people who have finished at least one book–to find out how they would answer this question:

HOW DO YOU KNOW WHEN YOUR LONGER WRITING PROJECT IS FINISHED?

One thing I learned is that it happens to be summer in other writers’ universes as well; despite that, I heard back from a dozen or so of these exemplary, hard-working folks, and the advice is so stellar that I decided to pull together my sorry summery self and share it with you. Here goes.

1. DO YOUR HOMEWORK!

Carol Tice at Make a Living Writing has written two traditional print books, plus a dozen self-published nonfiction e- books. Her advice is to “write from research, create an outline, follow your process, and don’t look back.” Her research (my “homework” in the sub-heading) encompasses not only the content, but also research into how you’ll position, design, and deliver the content.

books. Her advice is to “write from research, create an outline, follow your process, and don’t look back.” Her research (my “homework” in the sub-heading) encompasses not only the content, but also research into how you’ll position, design, and deliver the content.

She continues: “Every book I’ve worked on that I wrote from scratch (i.e. not repurposed from a course, podcast, or blogposts) begins with online research to see the best headline and concept positioning compared with what’s already out there. From there, we create a chapter outline. I write to my outline and ideally get some feedback on it from my audience, to see if there are major points I’ve neglected to include. Add them in, and then the draft is done.

“From there, most of my books go through three phases of editing–I have one staffer who does a first pass, then I edit, and then a professional editor. Final read by me (only minor changes permitted at this point!) and it’s done and ready for my designer. Good planning at the start makes sure you can roll through to the end and [not] get derailed or start second-guessing the direction.

“Final tips: think multiple projects, and give yourself deadlines! I wasted two years writing my first e-book and making it super long. I should have put it out as a shorter series of ebooks instead. Most e-books are short, so if you’re going that route, remember to save side trails and related ideas for future e-books. The easiest way to sell a book is…with the next book.”

To read more on this subject from Carol, check out her blog (linked above), her community for freelance writers, or this post.

2. SOW THE SEEDS, SEE WHAT SPROUTS, THEN…

At her website, Writing It Real, Sheila Bender includes all manner of great advice–classes too–directed toward writing poetry, essays, creative-nonfiction, and memoir. She’s also the author of several wonderful books about writing and the writing life. She sent me a whole page of finishing ideas, addressing the process in five different genres. My favorite was this:

At her website, Writing It Real, Sheila Bender includes all manner of great advice–classes too–directed toward writing poetry, essays, creative-nonfiction, and memoir. She’s also the author of several wonderful books about writing and the writing life. She sent me a whole page of finishing ideas, addressing the process in five different genres. My favorite was this:

“My instructional book, Writing and Sharing Personal Essays, uses an agricultural metaphor: prepare the soil, sow the seeds, see what sprouts, harvest the crop, bring it to market.”

It strikes me that this is a poet’s take on what Carol Tice says (above). Sowing the seeds is the planning and thinking stage. Seeing what sprouts is the stage during which we get it all scribbled out. Harvest–that has to be editing (but also finding good editing help, and accepting it gracefully). Once it’s harvested, we have to bring it to market and that requires that we trust the process we’ve been through and submit the dang thing.

I recently bought a copy of Sheila’s book, Sorrow’s Words: Writing Exercises to Heal Grief, and highly recommend it. Click on this link to go to her books page on her website.

3. LET IT GO

Kathleen Kirk at EIL (Escape Into Life), an on-line literary and arts journal, had this to say: “Sometimes I think it (anything) is finished when it finally gets published, but sometimes not even that  is true, as I have fiddled with individual poems later, developing a book manuscript, sometimes with an editor’s help. I live with some poems for many years, continuing to trust them or to tweak them. Other things I look at and say, ‘Did I write that?'”

is true, as I have fiddled with individual poems later, developing a book manuscript, sometimes with an editor’s help. I live with some poems for many years, continuing to trust them or to tweak them. Other things I look at and say, ‘Did I write that?'”

Kathleen serves as Poetry Editor and Editor at Large for Escape Into Life, and she has several books of poetry, including Interior Sculpture (Dancing Girl Press, 2014) and ABCs of Women’s Work (Red Bird, 2015), with The Towns forthcoming from Unicorn Press in 2018. Her personal blog is Wait! I Have a Blog?!

4. STOP WRITING

Are you starting to see a pattern here? Sue Anne Dunlevie, the author of Stress Management Decoded: The Practical Path to Inner Peace for Busy Women, also emphasized working with an editor, having faith in the process, and STOPPING. Could it be so simple?

Are you starting to see a pattern here? Sue Anne Dunlevie, the author of Stress Management Decoded: The Practical Path to Inner Peace for Busy Women, also emphasized working with an editor, having faith in the process, and STOPPING. Could it be so simple?

“For my Amazon Kindle book, I had an editor. She was great and helped me realize where I needed to add info and when I needed to stop writing! I have since done some short eBooks for my blog readers and I make sure that 1) I’m giving a lot of value and 2) giving them actionable content that they can use right away.”

Notice that final key, too, in Sue’s advice: ACTIONABLE CONTENT. To read more about and from Sue Anne, take at look at successfulblogging.com.

5. BE IN CONVERSATION WITH YOUR WRITING

Joannie Stangeland has several books of poetry (including In Both Hands from Ravenna Press), all of which grace my shelves. When I asked her how she knows when a book is done, she described the process as a conversation:

“For me, revising or editing a poem or even an entire manuscript is a conversation. While I’m looking and learning what the poem says, I’m also questioning it and listening to it. At some point in the exploration or polishing, we’ve said all that we have to say—and that pause in the conversation tells me it’s ready to send out. The dialog might start up again in the future, but for now, it’s finished.”

To find more about Joannie’s books, visit her blog, joanniestangeland.com.

6. TRUST YOUR GUT

Janice Hardy, whose site, Fiction University, is a recent discovery for me, took a visceral approach in her response. You get tired, you follow hunches, the manuscript nags, boredom attacks, and so forth. Or, in her exact words:

“For me, a manuscript is  done when I’m tired of reading it, and all I’m doing is making insignificant edits here and there. Those edits are mostly changing a word or moving a comma. Fiddling with the text only because I’ve read it so many times it no longer feels fresh, not because it actually needs it.

done when I’m tired of reading it, and all I’m doing is making insignificant edits here and there. Those edits are mostly changing a word or moving a comma. Fiddling with the text only because I’ve read it so many times it no longer feels fresh, not because it actually needs it.

“It’s not done if I’m changing the plot, story, or characters at all, or if there’s a bit nagging at me that isn’t right. When my gut is telling me something, I try to listen even if I don’t want to spend any more time on the manuscript.

“Be wary about thinking a manuscript is done just because you’re bored with it. Sometimes that means it is done, but it can also mean you need a break from it. Set it aside for a week or two and read it again before deciding.”

I have a stack of Janice’s books, and Understanding Show, Don’t Tell: (And Really Getting It) (2016) completely changed the way I edit.

7. CARE MORE ABOUT THE ACT OF WRITING THAN THE ART OF FINISHING

Another good friend and poet, Esther Helfgott, also offered a visceral response to my question. Initially, she emailed back only the enigmatic, “When my stomach stops hurting.” I wasn’t sure what to make of that, or what to do with it, but the very next day, a poem arrived in my in-box. I think I can summarize what she’s saying with, “Trust the process, and more will be revealed.” Esther is, by the way, a woman who gets PLENTY finished. She has a blog, and several books, including Dear Alzheimer’s, which is a tribute to her late husband, Abe, and Listening to Mozart: Poems of Alzheimer’s. (You can click on the link to Esther’s blog to read more about her books.) She introduced the poem with these words:

“You’ve gotten me started on this poem, which is not finished, of course; but you’re welcome to use perhaps the idea of it and, if not, that’s ok too. This exercise has made me see that I care more about the act of writing itself than the art of finishing!

“I had a great conversation with someone the other day about the biography I’m writing. She was really interested in my work so I went on and on about my research and how wonderful it was to discover this piece of history and how much I was getting done–writing articles connected with the main work–and I was so excited that someone was so interested but the last thing she said to me when leaving was, ‘When will it be published?’ It really broke my heart.”

The poem is beautiful, and depicts the poet’s mother sewing. Esther includes a comparison to loving the way the parts of the craft of sewing “sang together” and how writing can be like that, too. I think I will build an entire blogpost around it, with Esther’s permission.

8. DONE IS BETTER THAN PERFECT

If you’ve been a follower of my blog for very long, then you know that last year I hired an organizing expert–my fabulous clutter-control coach, Monika Kristofferson. Monika not only assisted me in getting rid of a truckload of stuff, but she also inspired the heck out of me as a creator. She gives you her book at your first consultation, by the way, or you can buy it, here. She has also written a book about organizing for the holidays.

If you’ve been a follower of my blog for very long, then you know that last year I hired an organizing expert–my fabulous clutter-control coach, Monika Kristofferson. Monika not only assisted me in getting rid of a truckload of stuff, but she also inspired the heck out of me as a creator. She gives you her book at your first consultation, by the way, or you can buy it, here. She has also written a book about organizing for the holidays.

“I found that there were several feeling ‘finished’ milestones. Each chapter of my book covers a specific productivity topic and the first step of being finished was in writing the content for each chapter. The chapters don’t flow one into the other like a novel but are complete on their own and I felt good about the information in each chapter. The next step that felt finished came when I completed the edits from my editor, from adding content to moving chapters around. After reading and reading and editing, editing and then editing some more, I really did feel ‘finished’ with the book in three ways. I felt the content would help other people, I was weary of reading my own book and I knew it was possible to go back to Amazon to fix any errors that may have slipped through the cracks. At that point I felt that done was better than perfect and it was time to share it with the world.”

I am compelled to point out that this paragraph presents writing through the lens of a professional organizer, with the chapters appearing like rooms or maybe like large pieces of furniture that one can move around. At the same time, this description conveys something essential about Monika’s attitude. While we were decluttering, she never made me throw anything out. Put it in a box and label it, maybe, but I could keep it. “You can come back to it later,” she’d say. She seems to regard writing the same way, not holding it in a death-grip (as I have been guilty of), but lightly.

You can find Monika at http://efficientorganizationnw.com/

9. HAVE YOU TOLD THE STORY YOU WANTED TO TELL?

I found this light touch, again, in Paul Marshall’s description of his process. My very good friend and fellow-labster,  he needn’t have been the only guy here, as I emailed several. But he was the only one who got back to me (which I trust does not mean that his summer was dull). About a year back, Paul wrote and self-published his book–Building a Boat: Lessons from a 30 Year Project–and from the outside it looked as though he did it in record time. Of course one could point out that it took 30 years for him to write this book.

he needn’t have been the only guy here, as I emailed several. But he was the only one who got back to me (which I trust does not mean that his summer was dull). About a year back, Paul wrote and self-published his book–Building a Boat: Lessons from a 30 Year Project–and from the outside it looked as though he did it in record time. Of course one could point out that it took 30 years for him to write this book.

“When a story is finished depends totally on the story one wants to tell. In my book I was constantly being pulled off track by memories or images that wanted me to tarry a while with them. The same was true of the ending. Why hadn’t I spent time elaborating on various aspects of the story, making historical connections that might deepen the context or flesh out some idea? In the end the story I wanted to tell was complete. Obviously, not sufficiently to receive a Pulitzer but as good as I could do. I had to stop worrying about readers and their questions or confusions.

“Just this was left, had I told the story that I wanted to tell? I had and so I was finished.”

This short book is a memoir, by the by, not a boat-building manual, and I’ve bought a few to give as gifts for the men in my life. On the other hand, while it’s about the manly art of boat building, the story will apply to anyone who has put off a dream (including a writing dream)–then resurrected and resolved it.

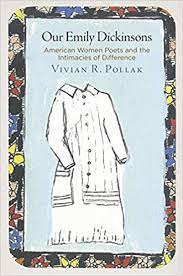

10. DON’T DO WHAT EMILY DID?

But you might try being as attitude-y about your process as an Emily Dickinson. This is something I’ve been learning  from my mentor, Vivian Pollack, for at least 25 years, as she served as my dissertation adviser when I was working on my Ph.D. in American Literature. In addition to being a university professor and a former president of The Emily Dickinson International Society, she is the author of several books. I consider her Dickinson: The Anxiety of Gender (1984), to be a classic in Dickinson scholarship; her latest book is Our Emily Dickinsons: American Women Poets and the Intimacies of Difference (2016). Typical of the way Dr. Pollak’s mind works, her paragraph on “how to know when it’s finished, circled around to E.D.:

from my mentor, Vivian Pollack, for at least 25 years, as she served as my dissertation adviser when I was working on my Ph.D. in American Literature. In addition to being a university professor and a former president of The Emily Dickinson International Society, she is the author of several books. I consider her Dickinson: The Anxiety of Gender (1984), to be a classic in Dickinson scholarship; her latest book is Our Emily Dickinsons: American Women Poets and the Intimacies of Difference (2016). Typical of the way Dr. Pollak’s mind works, her paragraph on “how to know when it’s finished, circled around to E.D.:

“How to finish or to know when something is finished? Sometimes it feels finished and at other times there is someone asking for it to be finished or time is just running out. E.g. our semester starts in about 4 weeks and I have a project I want to finish before then. Really I want to finish it before going to Amherst next Wednesday and we shall see what we shall see. But did I misunderstand your question: are you asking how I personally know when one of my efforts is finished or are you asking me as a reader whether I feel satisfied with the completeness of some works? Or–gulp–are you asking me what someone like Emily Dickinson had to say about being finished? ‘It is finished can never be said of us.’ Yes, that’s Emily–perhaps the queen of unfinishing.”

“How to finish or to know when something is finished? Sometimes it feels finished and at other times there is someone asking for it to be finished or time is just running out. E.g. our semester starts in about 4 weeks and I have a project I want to finish before then. Really I want to finish it before going to Amherst next Wednesday and we shall see what we shall see. But did I misunderstand your question: are you asking how I personally know when one of my efforts is finished or are you asking me as a reader whether I feel satisfied with the completeness of some works? Or–gulp–are you asking me what someone like Emily Dickinson had to say about being finished? ‘It is finished can never be said of us.’ Yes, that’s Emily–perhaps the queen of unfinishing.”

“The problem most writers have with finishing work is that they rely on pure rational will and aggressive determination to get the job done. When they feel themselves flagging in their efforts they whip themselves even harder, driving the writing on until it’s done. This causes tension in the body and a forced stiltedness in the work.

“The problem most writers have with finishing work is that they rely on pure rational will and aggressive determination to get the job done. When they feel themselves flagging in their efforts they whip themselves even harder, driving the writing on until it’s done. This causes tension in the body and a forced stiltedness in the work.

“Creative work is not a mechanical cog that can be turned out ever faster on an assembly line. Creative work is a living, breathing, organic collection of energy. It’s like fruit on a tree. Every piece of fruit ripens in its own time, and its ripeness corresponds to the current season in perfect harmony. Instead of ripping green apples off the tree and pounding them into applesauce anyway, writers would do much better to practice the art of patience and leave the fruit alone until it is ready to be picked.”

So there you have it–a baker’s dozen of expert writers weighing in on how they know when the writing is done. This post has taken me several days (or weeks!) to jiggle into shape, and it gave me an opportunity to put some of the advice into practice. My comments had to ripen, too–maybe “simmer” is the metaphor I want. And I found that working with, retyping, excerpting, and arranging the advice all helped it to sink in.

Now please excuse me while I sneak off to finish my novel. (And if you have some advice, I’d love to see your thoughts in the comments!)

Priscilla is one of my oldest friends, and of course I contacted her and asked a few questions. She responded with a treatise on how to gather poems and turn them into books. I am happy to share all her largesse here. (For more along this vein, see her brilliant, short book Minding the Muse.) I started the email exchange by asking how books are made; she went straight to the poems themselves:

Priscilla is one of my oldest friends, and of course I contacted her and asked a few questions. She responded with a treatise on how to gather poems and turn them into books. I am happy to share all her largesse here. (For more along this vein, see her brilliant, short book Minding the Muse.) I started the email exchange by asking how books are made; she went straight to the poems themselves:and then another and then another. I’ve composed 667 poems so far, the first in the 1970s. I keep the poems in three-ring binders, latest version only, in chronological order, with the date of composition (not dates of revision) at the bottom, along with any publication data. This is a resource base essential to my process of shaping a book.

If you have been my student or talked about writing with me, then you probably already know that Priscilla Long, author of The Writer’s Portable Mentor and other books, has been my friend for 30 years.

If you have been my student or talked about writing with me, then you probably already know that Priscilla Long, author of The Writer’s Portable Mentor and other books, has been my friend for 30 years.

books. Her advice is to “write from research, create an outline, follow your process, and don’t look back.” Her research (my “homework” in the sub-heading) encompasses not only the content, but also research into how you’ll position, design, and deliver the content.

books. Her advice is to “write from research, create an outline, follow your process, and don’t look back.” Her research (my “homework” in the sub-heading) encompasses not only the content, but also research into how you’ll position, design, and deliver the content. At her website,

At her website,  is true, as I have fiddled with individual poems later, developing a book manuscript, sometimes with an editor’s help. I live with some poems for many years, continuing to trust them or to tweak them. Other things I look at and say, ‘Did I write that?'”

is true, as I have fiddled with individual poems later, developing a book manuscript, sometimes with an editor’s help. I live with some poems for many years, continuing to trust them or to tweak them. Other things I look at and say, ‘Did I write that?'” Are you starting to see a pattern here? Sue Anne Dunlevie, the author of

Are you starting to see a pattern here? Sue Anne Dunlevie, the author of

done when I’m tired of reading it, and all I’m doing is making insignificant edits here and there. Those edits are mostly changing a word or moving a comma. Fiddling with the text only because I’ve read it so many times it no longer feels fresh, not because it actually needs it.

done when I’m tired of reading it, and all I’m doing is making insignificant edits here and there. Those edits are mostly changing a word or moving a comma. Fiddling with the text only because I’ve read it so many times it no longer feels fresh, not because it actually needs it.

If you’ve been a follower of my blog for very long, then you know that last year I hired an organizing expert–my fabulous clutter-control coach,

If you’ve been a follower of my blog for very long, then you know that last year I hired an organizing expert–my fabulous clutter-control coach,  he needn’t have been the only guy here, as I emailed several. But he was the only one who got back to me (which I trust does not mean that his summer was dull). About a year back, Paul wrote and self-published his book–

he needn’t have been the only guy here, as I emailed several. But he was the only one who got back to me (which I trust does not mean that his summer was dull). About a year back, Paul wrote and self-published his book– from my mentor,

from my mentor,  “How to finish or to know when something is finished? Sometimes it feels finished and at other times there is someone asking for it to be finished or time is just running out. E.g. our semester starts in about 4 weeks and I have a project I want to finish before then. Really I want to finish it before going to Amherst next Wednesday and we shall see what we shall see. But did I misunderstand your question: are you asking how I personally know when one of my efforts is finished or are you asking me as a reader whether I feel satisfied with the completeness of some works? Or–gulp–are you asking me what someone like Emily Dickinson had to say about being finished? ‘It is finished can never be said of us.’ Yes, that’s Emily–perhaps the queen of unfinishing.”

“How to finish or to know when something is finished? Sometimes it feels finished and at other times there is someone asking for it to be finished or time is just running out. E.g. our semester starts in about 4 weeks and I have a project I want to finish before then. Really I want to finish it before going to Amherst next Wednesday and we shall see what we shall see. But did I misunderstand your question: are you asking how I personally know when one of my efforts is finished or are you asking me as a reader whether I feel satisfied with the completeness of some works? Or–gulp–are you asking me what someone like Emily Dickinson had to say about being finished? ‘It is finished can never be said of us.’ Yes, that’s Emily–perhaps the queen of unfinishing.”

“The process of finishing a work typically overlaps with its first reading or viewing, its first public exposure to your peers or to your first (probably small) audience. At this point you may receive some useful feedback. Even with no feedback, the act of presenting in itself helps you to see work from the outside, to get distance from it. This in turn helps you see where to make necessary tweaks. Completing works and putting them out in the world is part of the creative process….And once you’ve released it to the world, you’ve cleared room for new works.”

“The process of finishing a work typically overlaps with its first reading or viewing, its first public exposure to your peers or to your first (probably small) audience. At this point you may receive some useful feedback. Even with no feedback, the act of presenting in itself helps you to see work from the outside, to get distance from it. This in turn helps you see where to make necessary tweaks. Completing works and putting them out in the world is part of the creative process….And once you’ve released it to the world, you’ve cleared room for new works.” “The problem most writers have with finishing work is that they rely on pure rational will and aggressive determination to get the job done. When they feel themselves flagging in their efforts they whip themselves even harder, driving the writing on until it’s done. This causes tension in the body and a forced stiltedness in the work.

“The problem most writers have with finishing work is that they rely on pure rational will and aggressive determination to get the job done. When they feel themselves flagging in their efforts they whip themselves even harder, driving the writing on until it’s done. This causes tension in the body and a forced stiltedness in the work.

friendships, in getting to the gym), someone was bound to say, “How’s that working for you?”

friendships, in getting to the gym), someone was bound to say, “How’s that working for you?” If you usually wait for inspiration to strike you, try seeking it out instead. Buy a book of exercises and actually do them. Read the sorts of poems or stories you would like to write. Read one poem and write it out in your notebook. What moves could you make that would be similar? How can your moves be radically different?

If you usually wait for inspiration to strike you, try seeking it out instead. Buy a book of exercises and actually do them. Read the sorts of poems or stories you would like to write. Read one poem and write it out in your notebook. What moves could you make that would be similar? How can your moves be radically different?