Patricia Fargnoli (1937-2021)

WINTER, Patricia Fargnoli. Hobblebush Books, Brookline, NH, 2013, 88 pages, $18, paper, https://www.hobblebush.com.

When MoonPath’s Lana Hechtman Ayres told me Patricia Fargnoli had been her teacher and mentor, I went looking  for her. Winter, the sixth volume in the Hobblebush Granite State Poetry Series, was the first to arrive, and is now on sale for $9 at Hobblebush Books (use this link: https://www.hobblebush.com/product-page/winter).

for her. Winter, the sixth volume in the Hobblebush Granite State Poetry Series, was the first to arrive, and is now on sale for $9 at Hobblebush Books (use this link: https://www.hobblebush.com/product-page/winter).

I have fallen hard for this book, and this poet. In “The Horse,” she begins:

I let the horse into my apartment,

pushed back chairs,

shoved the rattan chest

up against the tall bookcases…

Horses abound in this book. What’s not to love?

In addition to any other praise I might dish out, it’s a perfect book to read on a cold and rainy January day. Yes, New Hampshire, snow, but it works its spell here in the Pacific Northwest, too: “[I] found a sad music in the fork of an ash tree, / a music made of wind and the tuning forks of stars” (“Glosa”). As Meg Kearney tells us on the back cover, Fargnoli has “listened deeply to the silence of winter.”

Many of the poems in Winter are about dreams. A line from “Beginning of Winter—A Sijo Sequence”: “Last night in the dream I was hungry, but there was no food.” Or the ending of “Letter to my Double”:

Your dreams tell you what you want:

a man’s arms around your body, a safe place near water,

a bus that arrives on time to carry you home.

She captures the mundane, that daily seemingly ordinary life that we all find ourselves up against, while lifting it above the ordinary. Home, here, is not just the physical place where you lie down at night. The following poem, too, is about an actual place (Ireland, which made me choose it), but it transports us into a dreamscape:

Galway

after Tranströmer’s “Track”

Thousands of crows flew through the Irish dusk

toward the copse of dark plane trees not far from here,

between the university and the famous river,as when memories wing in from your past

with their loud continuous cawing

and then move beyond you, you don’t know where.Or as when someone dies and her spirit rises

to join the others who are leaving the world’s sadness

to find a resting place in the quiet night branches beyond you.The crows streamed past the high clerestory windows.

Dusk. The small wood they entered. The silver river.—Patricia Fargnoli (from Winter)

Notice how the crows are actual, but spur memories that “wing in from your past / with their loud continuous cawing.” Sorry, but I just want to gush on and on. I’ve been thinking (a lot) about how one gets the evanescent, the transcendent into one’s poems, and Fargnoli offers a master class.

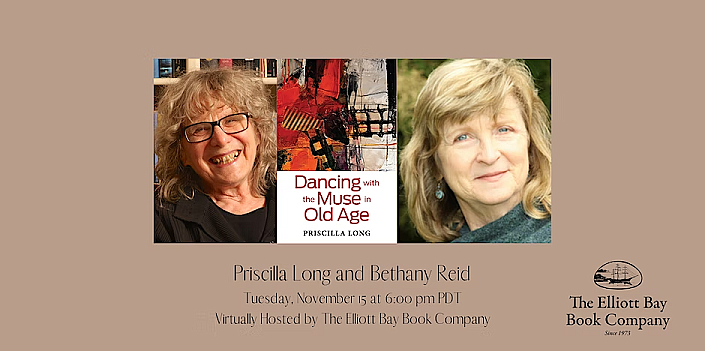

When I was working on The Pear Tree, I often thought of something Priscilla Long says in her chapter, “Art and Elegy,” in Dancing with the Muse in Old Age:

“Is it too obvious to say that one advantage of growing old is to remain alive to the beauty and suffering of the world? To make an elegy is to express that beauty and that suffering.” —Priscilla Long

The elegy, the courage to elegize, is a strength of Fargnoli’s Winter.

To learn more about Patricia Fargnoli, visit her page at Hobblebush Books (“Read Sample” offers a PDF of the opening pages of Winter, including the informative table of contents and the first few poems). When I Googled her name I found several video recordings of “Winter’s Grace,” perhaps her best-known poem (which you can also find at https://www.writersalmanac.org/index.html%3Fp=11037.html). Simply gorgeous.

Ricardo Reis, and Álvaro de Campos. Pessoa created entire biographies for these alter-egos and considered them mentors and colleagues. He is, Zenith tells us, “an editor’s nightmare,” but also a treasure trove:

Ricardo Reis, and Álvaro de Campos. Pessoa created entire biographies for these alter-egos and considered them mentors and colleagues. He is, Zenith tells us, “an editor’s nightmare,” but also a treasure trove: I’ve been reading—or reading around in—another strange book, this one titled The Ashley Book of Knots. It was written and illustrated (3384 numbered illustrations) by Clifford W. Ashley, and first published in 1944. My copy belonged to my paternal grandfather (a Navy Seabee during WWII, which must explain why the book looks so well-read; I could go on a bit about my grandfather—as he was in his 40s and had 5 children when he enlisted; he kept his paychecks [from what I’m told], but wrote letters home signed, “Your poet, Gene”). His name and the date, Eugene H. King, 10/14/46, are written on the inside front cover. I can guess that the book came to belong to my father in 1959, when his father died. Since 2012, it has been mine, and this year I finally took it down from the shelf.

I’ve been reading—or reading around in—another strange book, this one titled The Ashley Book of Knots. It was written and illustrated (3384 numbered illustrations) by Clifford W. Ashley, and first published in 1944. My copy belonged to my paternal grandfather (a Navy Seabee during WWII, which must explain why the book looks so well-read; I could go on a bit about my grandfather—as he was in his 40s and had 5 children when he enlisted; he kept his paychecks [from what I’m told], but wrote letters home signed, “Your poet, Gene”). His name and the date, Eugene H. King, 10/14/46, are written on the inside front cover. I can guess that the book came to belong to my father in 1959, when his father died. Since 2012, it has been mine, and this year I finally took it down from the shelf. book, Dancing with the Muse in Old Age. After losing my father at age 82 to a stroke; after accompanying my mother through ten years of Alzheimer’s, stroke, and skilled-nursing care, then her death at age 86; I had pretty much decided that I’d better get things done right now, because I would be decrepit very very soon.

book, Dancing with the Muse in Old Age. After losing my father at age 82 to a stroke; after accompanying my mother through ten years of Alzheimer’s, stroke, and skilled-nursing care, then her death at age 86; I had pretty much decided that I’d better get things done right now, because I would be decrepit very very soon.