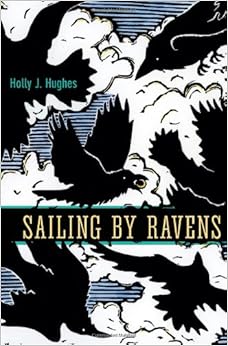

Sailing by Ravens

A month or so ago I was fortunate to be able to have lunch with an old friend, poet Holly J. Hughes. I have mentioned her on this blog before, as she is one of the authors of The Pen and Bell (with Brenda Miller). And, as if catching Holly between a thousand other calls for her attention wasn’t accomplishment enough, she gave me a copy of her new poetry book, Sailing by Ravens, published by University of Alaska Press (2014).

“Read the poems in order,” Holly told me as we parted. But I always read poetry books in order, gobbling them up (in fact) like novels–not short stories or novellas, by the way, novels, because the best books of poetry have just as much emotional content. Not easy, not on the surface like a more conventional narrative, but there nonetheless.

Sailing by Ravens did not disappoint. I knew from reading her earlier chapbook, Boxing the Compass (Floating Bridge, 2007), that learning to navigate rough seas would be interwoven here with the trickier navigation of a marriage and its end. But in Sailing, the metaphor of navigation is extended. Holly spent 30 summers working in (on?) the waters of Alaska (I’m quoting a review by Tim McNulty), “fishing, skippering a sailing schooner, and working as a ship’s naturalist. Her poems shimmer with authenticity.” The poems about human relationships shimmer with authenticity, too. And all of the poems benefit from Holly’s willingness to carefully observe her world (and read about it), no matter how painful, or how beautiful. The prose poem, “Navigating the Body,” had an epigraph that sent me scurrying for a pen (“No land in human topography is less explored than love” -Jose Ortega y Gasset) and then took me into unexpected territory:

Navigating the Body

Our bodies an accumulation of coordinates, paths not taken, streets pulled up short, lonely alleys, dead ends. In the dark I reach out, find crows’ crooked feet, scrim of scars–proud flesh–read each scar, remember its time and place, its bright spurt of blood. These are the landscapes we think we know. These are the landscapes we’ll never know. In the dark, we make our way, mapping and remapping the continents each night. Like Scheherazade we keep doing this; like Scheherazade, this is how we stay alive.

Confession: I’ve read this book three times. The first time through, the forms (sestina, villanelle, ghazal and others) as well  as some of the subjects (Mercator, Flavia Gioia, John Harrison are only three) were lost on me. But as I read and absorbed the notes, and reread the poems, the book seemed to have a trapdoor in its floor that dropped me down into another level (into water? over my head?). It was only then that I began to appreciate the encyclopedic knowledge that I was being offered, in addition to the poetics, “Isinglass darkened, but not enough to shield our Eyes, / rays of Sun Fractal, spatterpaint retinas, Shutter stutters.” (Just two lines from “The Forestaff 1587.” Such sounds!) So, not just argot, then, but shovel-loads of sound and sense detail, “scooped, shovel by shimmering shovel, into the fish hold” (“What She Can’t Say”).

as some of the subjects (Mercator, Flavia Gioia, John Harrison are only three) were lost on me. But as I read and absorbed the notes, and reread the poems, the book seemed to have a trapdoor in its floor that dropped me down into another level (into water? over my head?). It was only then that I began to appreciate the encyclopedic knowledge that I was being offered, in addition to the poetics, “Isinglass darkened, but not enough to shield our Eyes, / rays of Sun Fractal, spatterpaint retinas, Shutter stutters.” (Just two lines from “The Forestaff 1587.” Such sounds!) So, not just argot, then, but shovel-loads of sound and sense detail, “scooped, shovel by shimmering shovel, into the fish hold” (“What She Can’t Say”).

True, it takes a while to process such a treasure. But the trip is well worth it–and I’m pleased to heartily recommend this book.

Go to http://hollyjhughes.com/ to find more information about Holly J. Hughes (and links to reviews), and to Verse Daily to find another of her poems.

My mom has had a series of strokes and I’ve spent a lot of the last week in her hospital room. We thought we were losing her for a while there, but now she seems stronger and we’re just waiting to see. I’ll keep you posted. Meanwhile, a picture and a poem. (published in Jeopardy, spring 1992)

My mom has had a series of strokes and I’ve spent a lot of the last week in her hospital room. We thought we were losing her for a while there, but now she seems stronger and we’re just waiting to see. I’ll keep you posted. Meanwhile, a picture and a poem. (published in Jeopardy, spring 1992)