Priscilla Long: HOLY MAGIC

For our last book of my National Poetry Month jamboree, I reread Priscilla Long’s Holy Magic (MoonPath Press, 2020) and was once again astonished by its interplay of light and language, science and art, artists and song. If you don’t already have this book on your shelf, you should find a copy immediately. It’s a tutorial in how to live …and write. And though suffused with color and light, it isn’t afraid of the dark: death marches through these poems with its equal-opportunity scythe (Trayvon Martin, Matisse, Otis Redding, the poet’s sister, old friends, old loves, even a young T. Rex). Comprising seven sections and 56 poems, Holy Magic is … well, magic. I loved spending time in this book again, and delighted especially in soundplay that bumps and grinds and burns its way through every page:

Fire is cookery, crockery,

Celtic cauldrons worked

in iron or gold—smoke

of sacrificial fat.(from “Ode to Fire”)

Holy Magic is arranged by the color wheel, and so artists are invited in, not just their art—as it strikes me this morning, but their bodies—as in lines from this short poem dedicated to Meret Oppenheimer:

Kisses rot under logs.

Lost purple thrills

perfume purloined shadows(from “What Can Happen”)

Priscilla is one of my oldest friends, and of course I contacted her and asked a few questions. She responded with a treatise on how to gather poems and turn them into books. I am happy to share all her largesse here. (For more along this vein, see her brilliant, short book Minding the Muse.) I started the email exchange by asking how books are made; she went straight to the poems themselves:

Priscilla is one of my oldest friends, and of course I contacted her and asked a few questions. She responded with a treatise on how to gather poems and turn them into books. I am happy to share all her largesse here. (For more along this vein, see her brilliant, short book Minding the Muse.) I started the email exchange by asking how books are made; she went straight to the poems themselves:

First comes one poem and then another and then another and then one book

and then another and then another. I’ve composed 667 poems so far, the first in the 1970s. I keep the poems in three-ring binders, latest version only, in chronological order, with the date of composition (not dates of revision) at the bottom, along with any publication data. This is a resource base essential to my process of shaping a book.

I had written many dozens of poems and seen many published in journals before my first book, Crossing Over: Poems was published by The University of New Mexico Press. The shape of that book was strongly influenced by the press’s mission to publish poetry having to do with the West. I’ve lived in the West for almost forty years but grew up on a farm on the Eastern Shore of Maryland, so have many poems having nothing to do with the West. I put all the poems “of the West” in a file folder and went from there.

My second book, Holy Magic won the Sally Albiso Poetry Book award from MoonPath Press. This book is organized by the color wheel. I’m entranced with colors, their histories and lexicons and power to influence our moods and being. Often I work a theme in both poetry and prose, and this is the case with the color poems in Holy Magic. Thus I have poems titled “Blues Factory” and “The Blue Distance” and “Otis Redding” and also a prose piece titled “Blue Note.” As usual I already had some of the poems and also composed many new poems to fit into the wheel.

The third book, which I’ve just completed and started circulating, is titled Somewhere / Nowhere / Here: Cartographies of Home. For the first time, I had the title first, a capacious title, I think. Again I went into my old poems to seek ones that fit (and were not published in a previous book) and also wrote new poems. It has been a tremendously enjoyable project.

Completed before the pandemic, many of the poems in Holy Magic resonate with the last year’s solitude, from which we are only now emerging (I haven’t been inside a room with Priscilla for 14 months!). This poem, for one instance:

Tasks of Solitude

I am working out the vocabulary of my silence. —Muriel Rukeyser

To learn the dawn-purpled dark,

winter’s ruby light rinsing

rugs and books. To hone obedience

to cats: cat-blinks, cat-lappings.

To keen the silvery moon

hung on a dark throat.To unlock the door:

to enter the room of blue jugs.

To pour darkness from the coffeepot,

to learn the edges of darkness:

doorjamb, floorboard, candleflame,

the wavering edge where desire

thickens and vanishes like smoke.—Priscilla Long

But, lest you think she works in isolation, this:

Poetry happens as part of a community, beginning with the community of all poets, living and long gone. My friend Bethany Reid (of this blog) and I have worked together on poetry ever since we met in the poet Colleen McElroy’s workshop in 1989 in the MFA program at the University of Washington. In the past year we have undertaken the project of alternately finding a model poem to scrutinize and learn from. We then each compose a poem and we workshop them at a weekly meeting (on Zoom).

I have my monthly workshop, brilliant perceptive writers and visual artists that I cannot do without. We have been meeting for thirty years.

I am a teacher of writing, including poetry, but I take a class from time to time, mostly at Hugo House. I like classes that involve generating new poems: I’m about to take another from the fine poet and teacher Deborah Woodard. During the Holy Magic process I took a class from Sierra Nelson on writing color poems—a great class!

Reading a poem at one or another of the open mics around town (now around Zoom) is an essential piece of bringing a poem up.

My final question was to ask how she knows when a book is finished. How do you stop fidgeting with it, and send it into the world?

How do I tell a when book of poems is thoroughly cooked? After it is what I call “quote done” I read over the whole thing every morning. This can go on for months. Most mornings I find something to tweak. When several days go by with nothing to tweak, it might be done. Then there’s the process of having one or two poets read the whole thing. Their ideas are important and invariably prompt further tweaks.

Now I am in the floundering-about stage of shaping another book. What are my themes and concerns? Animals? The environment? Our beloved, broken country?

One more short poem to whet the appetite:

Consider the Red Pear

So what good are your scribblings? —H.D.

Beauty. The red pear

Cézanne painted among jade

and wood. Or Miró’s orange

sun rising in Red Sun. Or H.D.’s

charred apple tree blooming

in the bombed ruin of London.

The poet’s pale petals drift

down our long years. Art endures.

The stylus, the palette,

the pen, the quill endure.

In my backyard, a stone

Buddha laughs.—Priscilla Long

To learn more about Priscilla, visit her “about” page at her website, which includes this interview with Seattle book-goddess Nancy Pearl.

To purchase Priscilla’s books, or any books you have encountered on your journey with me this past month:

- visit your local independent bookstore

- mail-order or in person from the very efficient Elliott Bay Book Company

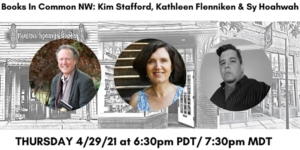

John L. Wright, Thursday, April 29th, 2021 6:30 – 7:30PM EST / 3:30 – 4:30 PST

John L. Wright, Thursday, April 29th, 2021 6:30 – 7:30PM EST / 3:30 – 4:30 PST Stafford (Singer Come from Afar,

Stafford (Singer Come from Afar,

Indigo (Copper Canyon, 2020), makes me want to take the mewling newborn sheaf of poems I’m calling a manuscript and dump them in the shredder. I’ll just start over.

Indigo (Copper Canyon, 2020), makes me want to take the mewling newborn sheaf of poems I’m calling a manuscript and dump them in the shredder. I’ll just start over.

presence, the sort of person who makes you feel visible, as though he is graced by your presence, rather than the other way around. He is the poet laureate of Redmond, Washington, and his book, All Our Brown-Skinned Angels (MoonPath Press, 2012) was nominated for the 2013 Washington State Book Award in Poetry. To learn more about him, visit his website or go to

presence, the sort of person who makes you feel visible, as though he is graced by your presence, rather than the other way around. He is the poet laureate of Redmond, Washington, and his book, All Our Brown-Skinned Angels (MoonPath Press, 2012) was nominated for the 2013 Washington State Book Award in Poetry. To learn more about him, visit his website or go to