National Poetry Month: poetry book #1

Welcome to National Poetry Month!

If you are looking for a full rundown on what NPM is, skip over to https://www.napowrimo.net/ for a prompt a day and links to lots else. I also want to recommend Chris Jarmick’s blog, Poetry Is Everything. Chris, the owner of BookTree in Kirkland, Washington, will happily provide you with great quotes, prompts (daily in April!) and more links to poetry enthusiasts. I notice that rather than posting daily (as I believe he has in past Aprils), he is lumping the prompts into groups. If you are patient, you can find all of them. (And write 30 new poems!)

The world is never the same once a good poem has been added to it. A good poem helps to change the shape of the universe, helps to extend everyone’s knowledge of himself and the world around him.”

― Dylan Thomas

I have a modest goal this month of sharing a poem a day from the pile of books beside my desk. Some of these I read in August during the Sealey Challenge. Others — well, it’s about damn time. I may not read a book a day, and  I’m not pushing myself to do the usual blog reviews (though some may ensue), just this: one book, one poem.

I’m not pushing myself to do the usual blog reviews (though some may ensue), just this: one book, one poem.

Today it is Bones in the Shallows: poems from Mission Creek by Seattle poet Tito Titus. I reviewed his I can still smile like Errol Flynn (Empty Bowl Press, 2015) a few years back.

Tito Titus’s Mission Creek is located near Cashmere, Washington, and runs into the Wenatchee River. (Forgive me if I have any of this wrong.) As the title, Bones in the Shallows, suggests, the creek disappears every summer, drained by drought, by natural disasters, by greed. And in this slim book the creek, its creatures, and the people whose lives are lived on its banks are lovingly chronicled. Nature can heal us, Titus all but says, but only if we don’t destroy it first.

October coming down

How do you describe a creek?

Twenty cubic feet per second, the engineer said.I toss a slender woody shoot,

watch it meander through ripples,

fouette through eddies,

dive from glittering rocks,

float toward the Wenatchee River —

a one-legged ballerina, dancing

toward the ravenous Columbia.

Past the equinox now, the creek

runs ten-feet wide, a few inches deep.Still, no rain.

Now I know — in this parched tenth month —

how much water the upstream orchards

swallows when fish rotted on dry rocks:

enough to seduce innocent Coho

climbing freshwater reaches,

unaware of the Mission Creek murders

of their cousins, only a month before.Twenty cubic feet per second,

enough to pretend the drought is done.— Tito Titus

In “Last summer on Mission Creek,” we get a sense of all the beauty at stake:

Sumac leaves, stark and dark green,

wrestle summer winds.Creek burbles play. Their watery laughter

climbs our woody bank.

And this poignant line: “My life becomes more beautiful than I knew, / and faster, too!” That’s nature’s power to renew itself, and our spirits.

Titus and his wife of 40 years now live in Seattle. You can find a copy of Bones in the Shallows at Edmonds Bookshop, or visit www.poetfire.com.

$16.99, paper,

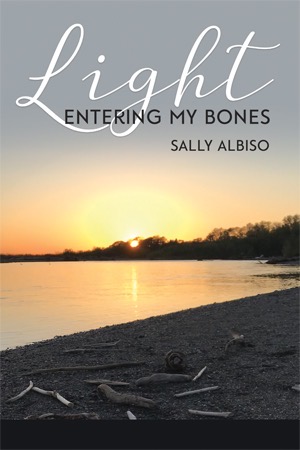

$16.99, paper,  If the poems feel at times brutal, they are brutally honest. They are also, as Karen Whalley points out in her appreciation of this book, “At their core, love poems,” “almost apologetic that [her husband] must be both witness and participant to her dying.” Her husband is an important character here. Consider the prose-poem, “Letter She Wrote Him,” where Albiso concludes, “Stars here, the sky a great camp with its fires lit, and daily the winter wren serenades, body turned to plea. Do you know the origin of mercy? From the Latin merces—the price paid for something.”

If the poems feel at times brutal, they are brutally honest. They are also, as Karen Whalley points out in her appreciation of this book, “At their core, love poems,” “almost apologetic that [her husband] must be both witness and participant to her dying.” Her husband is an important character here. Consider the prose-poem, “Letter She Wrote Him,” where Albiso concludes, “Stars here, the sky a great camp with its fires lit, and daily the winter wren serenades, body turned to plea. Do you know the origin of mercy? From the Latin merces—the price paid for something.”

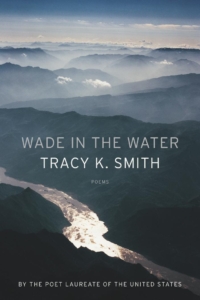

contemporary moment both to our nation’s fraught founding history and to a sense of the spirit, the everlasting. Here, private utterance becomes part of a larger choral arrangement as the collection includes erasures of the Declaration of Independence and correspondence between slave owners, a found poem composed of evidence of corporate pollution and accounts of near-death experiences, a sequence of letters written by African Americans enlisted in the Civil War, and the survivors’ reports of recent immigrants and refugees. Wade in the Water is a potent and luminous book by one of America’s essential poets.

contemporary moment both to our nation’s fraught founding history and to a sense of the spirit, the everlasting. Here, private utterance becomes part of a larger choral arrangement as the collection includes erasures of the Declaration of Independence and correspondence between slave owners, a found poem composed of evidence of corporate pollution and accounts of near-death experiences, a sequence of letters written by African Americans enlisted in the Civil War, and the survivors’ reports of recent immigrants and refugees. Wade in the Water is a potent and luminous book by one of America’s essential poets.

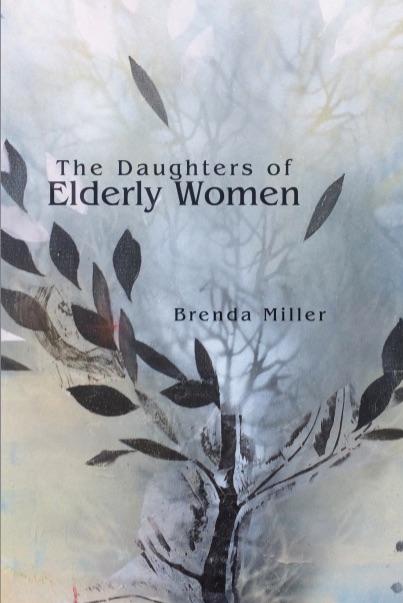

collection, but busy, too—like a care-taking daughter—with minutiae. Doctor appointments, dust, hospital rooms, post-it notes nudging a failing memory, loss.

collection, but busy, too—like a care-taking daughter—with minutiae. Doctor appointments, dust, hospital rooms, post-it notes nudging a failing memory, loss.