Jane Wong, How to Not Be Afraid of Everything

HOW TO NOT BE AFRAID OF EVERYTHING, Jane Wong. Alice James Books, 60 Pineland Drive, Auburn Hall, Ste. 206, New Gloucester, ME 04260, 79 pages, $17.95 paper, https://www.alicejamesbooks.org.

Jane Wong dedicates this book of poems to her grandparents “and those lost during the Great Leap Forward.” I looked  up the Great Leap Forward and learned that it was a 5-year campaign (1958-1962) to transform China from an agrarian economy into a communist society, which resulted in a famine costing 36 million lives (this, from the long poem “When You Died”; see Wikipedia on “The Great Leap Forward” at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Leap_Forward).

up the Great Leap Forward and learned that it was a 5-year campaign (1958-1962) to transform China from an agrarian economy into a communist society, which resulted in a famine costing 36 million lives (this, from the long poem “When You Died”; see Wikipedia on “The Great Leap Forward” at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Great_Leap_Forward).

This is a book haunted by ghosts, and by food. Understanding the Great Leap Forward helped me to better understand these obsessions. Some of the poems are from a granddaughter to grandparents; others are spoken by grandparents; sometimes it’s hard to tell which voice is whose. The themes are slightly broader: the life left behind, the Chinese immigrant experience in the United States, the wide-eyed (and fists curled) experience of the child taking everything in, hungrily, greedily. All of it.

Consider these lines, from a prose section at the end of “When You Died”:

I read about taro scrubbing, about villagers accused of stealing. To come clean, officials took turns beating them. How it all sounds like a game: ring around the roses, scrubbing skin to ashes, to all fall down. I falter on the page. What should be yours and wasn’t? What was swallowed whole? What roots, what ground to hold?

The review in Ploughshares called How Not to be Afraid of Everything:

“a triumph of formal ingenuity and in the hallucinatory intensity of the imagery throughout. All the more impressive is Wong’s fusing of that ingenuity with her exploration of her identity. … Wong’s new book compels us to remember that behind the broad designation “Asian American” is an infinite range of specific, distinct historical experiences.”

I found myself reading this book of poems as if it were a gripping novella, letting it wash over and scour me with its brilliance. The metaphors astound: “I break open, / hot cantaloupe in winter” (“The Frontier”); Judgment cuts through me / like a magician sawing // a woman in half” (“Wrong June”); “The nightly news clings to the wall like mold” (“Notes for the Interior”); “limbs loosened like an old garden hose” (“The Long Labors”); “Deep fry a cloud so it tastes like / bitter gourd or your father leaving—the exhaust of / his car, charred” (“After Preparing the Altar, the Ghosts Feast Feverishly”).

Here is one poem, admittedly more conventional than most. It’s really a book you have to hold in your hands and see for yourself.

I Put on My Fur Coat

And leave a bit of ankle to show.

I take off my shoes and make myself

comfortable. I defrost a chicken

and chew on the bone. In public

I smile as wide as I can and everyone

shields their eyes from my light.

At night, I knock down nests off

telephone poles and feel no regret.

I greet spiders rising from underneath

the floorboards, one by one. Hello,

hello. Outside, the garden roars

with ice. I want to shine as bright

as a miner’s cap in the dirt dark,

to glimmer as if washed in fish scales.

Instead, I become a balm and salve

my daughter, my son, the cold mice

in the garage. Instead, I take the garbage

out at midnight. I move furniture away

from the wall to find what we hide.

I stand in the center of every room

and ask: am I the only animal here?—Jane Wong

Somewhere I came across the idea of looking at the opening line of a book of poems (or one’s poetry manuscript) and the closing line. I’m not sure what Wong’s lines opening/closing lines do, except that they seem to catch the poet—or her persona—in the headlights:

Opening line: “Jane, deceived by _____ time and again, should not _____but she_____and slept with curled fists.”

Ending line: “Tell us, little girl, are you / hungry, awake, astonished enough?”

This is a prize-winning book, and if you look you’ll find all sorts of praise for it. You might start by visiting Jane Wong’s website, or the Poetry Foundation.

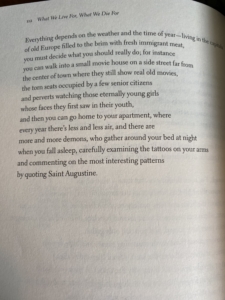

from a friend. She said, “You must read ‘Thirty Recommendations for Good Writing Habits,” so I did, and now I am reading the whole fat book from the beginning. This week, I am stuck at Davis’s essay, “Fragmentary or Unfinished: Barthes, Joubert, Hölderlin, Mallarmé, Flaubert.”

from a friend. She said, “You must read ‘Thirty Recommendations for Good Writing Habits,” so I did, and now I am reading the whole fat book from the beginning. This week, I am stuck at Davis’s essay, “Fragmentary or Unfinished: Barthes, Joubert, Hölderlin, Mallarmé, Flaubert.” “incoherence is preferable to a distorting order” (p. 220), then continues to comment on Mallarmé’s book after the death of his son, A Tomb for Anatole:

“incoherence is preferable to a distorting order” (p. 220), then continues to comment on Mallarmé’s book after the death of his son, A Tomb for Anatole:

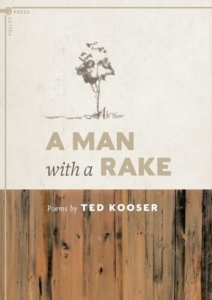

A MAN WITH A RAKE, Ted Kooser. Pulley Press (an imprint of Clyde Hill Publishing), Seattle / Washington D. C., 2022, 32 pages, $14 paper,

A MAN WITH A RAKE, Ted Kooser. Pulley Press (an imprint of Clyde Hill Publishing), Seattle / Washington D. C., 2022, 32 pages, $14 paper,  Beginning Poets ought to already be in your home library. (Even if you’re not a poet.) He is a former United States Poet Laureate, won a Pulitzer Prize for Delights and Shadows, etc. Anytime I’m told, “if you lived back east, you’d be better connected,” I think of Kooser, living in the midwest, writing about farms and farmers and farmhouses, working as an insurance agent for much of his career (!), and still here, still writing.

Beginning Poets ought to already be in your home library. (Even if you’re not a poet.) He is a former United States Poet Laureate, won a Pulitzer Prize for Delights and Shadows, etc. Anytime I’m told, “if you lived back east, you’d be better connected,” I think of Kooser, living in the midwest, writing about farms and farmers and farmhouses, working as an insurance agent for much of his career (!), and still here, still writing.