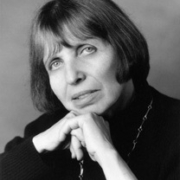

Linda Pastan 1932-2023

ALMOST AN ELEGY: NEW & LATER SELECTED POEMS, Linda Pastan. W. W. Norton & Company, 500 5th Avenue, New York N. Y. 10110, 2022, 122 pages, $30 cloth, www.wwnorton.com.

I began my research for this post by rereading Linda Pastan’s New York Times obituary. I could post a link and be done. The effusive praise you find there, the careful highlighting of biography—it’s exactly what I want to say.

“Linda Pastan writes about ordinary life — family, motherhood, aging, relationships, loss — in crystalline, transcendent verse often filled with humor, surprise, joy, and sorrow.” –Jill Bialosky

Yes, yes, yes, I kept thinking. I picked out a few crumbs, new (delicious) details I didn’t remember from my first reading of the obit in February. For instance, that  Pastan didn’t write poems when her children were small—

Pastan didn’t write poems when her children were small—

She took up writing again in the mid-1960s, trying a novel. But, she said, she found she was more interested in the descriptive language of what she was writing than the plot or characters. “My novel kept getting shorter and shorter, becoming almost a short story….Before long I realized that what it really wanted was to become a poem.”

—“Linda Pastan, Poet Who Plumbed the Ordinary, Dies at 90,” The New York Times, Feb. 3, 2023

While reading Pastan’s poems, I kept thinking, Look here, you don’t need to write a poem about this topic, she already wrote it! A feeling that Pastan herself addresses in her poem “Rereading Frost”: “Sometimes I think all the best poems / have been written already…”

I’m surprised, by the way, to learn that Pastan ever did not write. Some of her most memorable poems are about childbirth (see the NYT obit) and living with young children. In her earlier books, I found her mirroring back to me my own ages and stages in marriage and middle age. And now, as I plow toward seventy, I find she has more to teach me.

This poem, which I had not encountered previously, now has its page dogeared:

The Last Uncle

The last uncle is pushing off

in his funeral skiff (the usual

black limo) having locked

the doors behind him

on a whole generation.And look, we are the elders now

with our torn scraps

of history, alone

on the mapless shore

of this raw new century.—Linda Pastan

She also has an uncanny ability to predict the future, as if the world contains all its secrets, a jar of bees, and she has pressed her ear against it and listened hard. Her poem, “Somewhere in the World,” from Travelling Light (2011), opens with these stanzas:

Somewhere in the world

something is happening

which will make its slow way here.A cold front will come to destroy

the camellias, or perhaps it will be

a heat wave to scorch them.A virus will move without passport

or papers to find me as I shake

a hand or kiss a cheek.

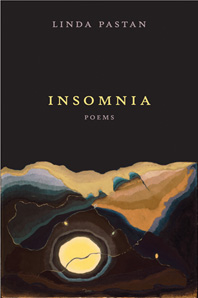

I saw Pastan at SAL several years ago, and wrote here about her book, Insomnia. I feel privileged to know her work from her earlier selected, Carnival Row, which I have picked up so often it is falling apart. Almost an Elegy is, equally, a treasure. Let me end with this poem from the “New Poems” section. Imagine me, inserting Pastan’s name:

Almost an Elegy: For Tony Hoagland

Your poems make me want

to write my poems,which is a kind of plagiarism

of the spirit.But when your death reminds me

that mine is on its way,I close the book, clinging

to this tenuous world the way the leavesoutside cling to their tree

just before they turn color and fall.I need time to read all the poems

you left behind, which piercethe darkness here at my window

but did nothing to save you.—Linda Pastan