Martha Silano, Reckless, Lovely

RECKLESS LOVELY, Martha Silano. Saturnalia Books, 105 Woodside Rd., Ardmore, PA 19003, 2014, 88 pages, $15 paper, https://saturnaliabooks.com.

I don’t think I’m alone in often picking up poetry books that remind me of my own poems—or poems a couple tiers up,  aspirational Bethany Reid poems. But today’s book spun me, and made me want to tear everything down and start over.

aspirational Bethany Reid poems. But today’s book spun me, and made me want to tear everything down and start over.

Maybe by taking better notes in the Astronomy class I took from Bruce Margon in 1985. Maybe by taking my kids to more museums and fewer playlands.

No matter, it was my great pleasure to spend the morning with these poems, and this poet, someone I am pleased to say is, like me, a northwest poet. Or “northwest poet plus the universe.” From the Big Bang to La-Z-boys, it’s a book that drenches you in specific language, leaves your head buzzing with Astro-physics and Da Vinci, madonnas and Neanderthals. (And so much Italian food.) I hardly know where to begin. Maybe by simply sharing this profile from the Saturnalia website—which does a splendid job of capturing Silano’s many achievements:

Martha Silano is the author of five volumes of poetry, including Gravity Assist, Reckless Lovely, and The Little Office of the Immaculate Conception, all from Saturnalia Books. She is also co-author of The Daily Poet: Day-by-Day Prompts for Your Writing Practice. Martha’s poems have appeared in Poetry, Paris Review, American Poetry Review, and the Best American Poetry series. Honors include North American Review’s James Hearst Poetry Prize and the Cincinnati Review’s Robert and Adele Schiff Poetry Prize. She currently teaches at Bellevue College and Seattle’s Hugo House.

“Inventive, chewy language,” Aimee Nezhukumatahil informs us. Precise language, marvelously multi-disciplinary, fantastic, inspiring.

To prove my point, one poem:

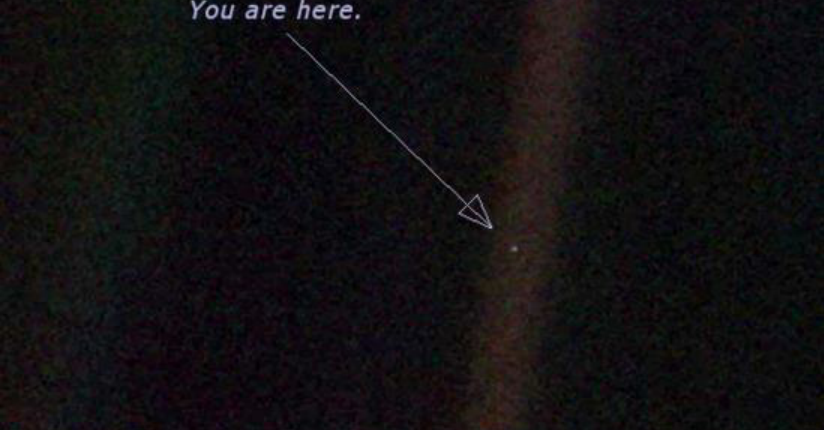

Pale Blue Dot

Candice Hansen Koharcheck, I’m not sure how

to pronounce your name, but you were the firstto spot it, this two-pixel speck otherwise known

as planet Earth. Sitting at your screen, shades drawn,office dark, you searched the digital photos sent back

by Voyager 1, four billion miles from your desk.And there it was, not the big blue marble swirling

with clouds and continents, not the one Apollo astronautsthe sheer beauty brought tears—thanking God and America,

declaring no need to fight over borders or oil; this was notthat view; this was how our planet might look to an alien.

And yet how close this photo came to not being taken at all;scientists arguing aiming the camera back at the sun

might fry the lens, questioning the worth of such a risk;this shot you say still gives you chills, dear Candice,

our planet bathed in the spacecraft’s reflective light.Pale blue dot lit by a glowing beam: I’m surprised

Christians didn’t have a hey day, though viewingHis crowning achievement requires squinting.

When NASA put it on display at the Jet Propulsion Lab,a blow-up print spanning fourteen feet, visitors touched

the pinprick so often the image needed constant replacing,perhaps because without the little arrow we wouldn’t know

which pinprick was home. And yet its barely-there-nessdoesn’t excuse the plastic bags, duct tape, juice packs,

sweat pants that lodge in the stomachs of whales. And yetits lack of distinction doesn’t pardon the brown-pudding goop

on the Gulf of Mexico’s floor, a goop in which nothing alivehas been found. To reckon that speck, mourn the loss

of the black torrent toad. To take it in, grasp its full weight,then turn toward a child’s insistent give me a ride in a rocket ship!

With meteors and turbulence! Like you, dear Candice, aloneand in the dark while a loved one’s asking Where are you going?

When are you coming back?—Martha Silano

A romp of a book. A gift. A call to ars poetica, and to arms.

To read more about Silano, visit her website, or this page at The Seattle Review (including a bit of a tutorial on endings, by the way); you can read a review of Reckless Lovely at The Los Angeles Review.

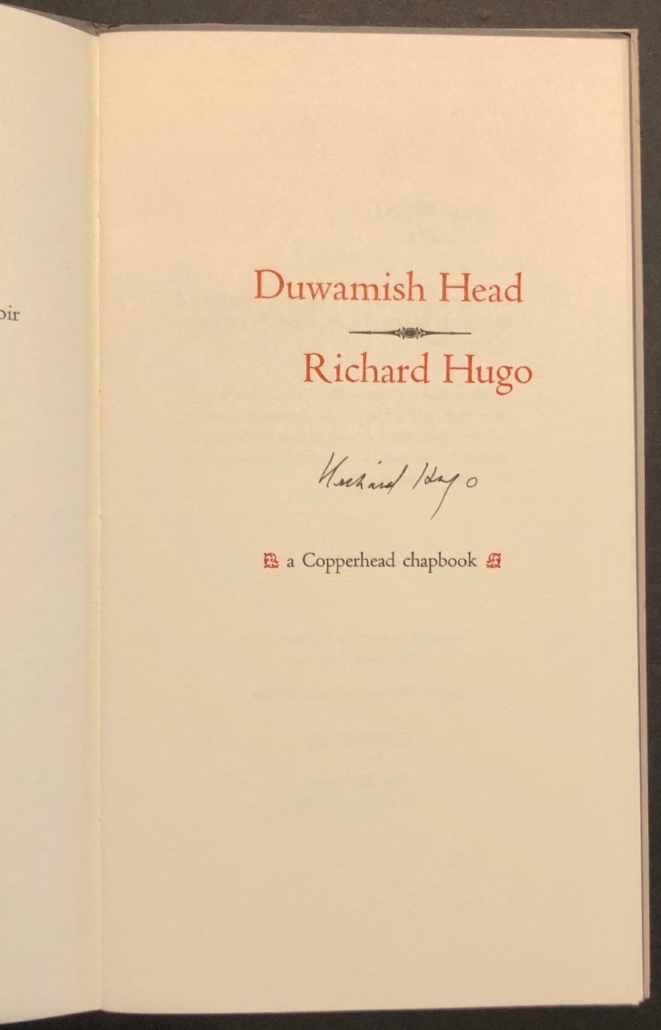

Richard Hugo, recently passed along to me by a friend who was letting go of some books. Copperhead no longer exists, and I couldn’t find any mention of it when I searched, but I suspect it was a precursor of Copper Canyon, as this chapbook was produced by Sam Hamill and Tree Swenson.

Richard Hugo, recently passed along to me by a friend who was letting go of some books. Copperhead no longer exists, and I couldn’t find any mention of it when I searched, but I suspect it was a precursor of Copper Canyon, as this chapbook was produced by Sam Hamill and Tree Swenson.

Ricardo Reis, and Álvaro de Campos. Pessoa created entire biographies for these alter-egos and considered them mentors and colleagues. He is, Zenith tells us, “an editor’s nightmare,” but also a treasure trove:

Ricardo Reis, and Álvaro de Campos. Pessoa created entire biographies for these alter-egos and considered them mentors and colleagues. He is, Zenith tells us, “an editor’s nightmare,” but also a treasure trove: I’ve been reading—or reading around in—another strange book, this one titled The Ashley Book of Knots. It was written and illustrated (3384 numbered illustrations) by Clifford W. Ashley, and first published in 1944. My copy belonged to my paternal grandfather (a Navy Seabee during WWII, which must explain why the book looks so well-read; I could go on a bit about my grandfather—as he was in his 40s and had 5 children when he enlisted; he kept his paychecks [from what I’m told], but wrote letters home signed, “Your poet, Gene”). His name and the date, Eugene H. King, 10/14/46, are written on the inside front cover. I can guess that the book came to belong to my father in 1959, when his father died. Since 2012, it has been mine, and this year I finally took it down from the shelf.

I’ve been reading—or reading around in—another strange book, this one titled The Ashley Book of Knots. It was written and illustrated (3384 numbered illustrations) by Clifford W. Ashley, and first published in 1944. My copy belonged to my paternal grandfather (a Navy Seabee during WWII, which must explain why the book looks so well-read; I could go on a bit about my grandfather—as he was in his 40s and had 5 children when he enlisted; he kept his paychecks [from what I’m told], but wrote letters home signed, “Your poet, Gene”). His name and the date, Eugene H. King, 10/14/46, are written on the inside front cover. I can guess that the book came to belong to my father in 1959, when his father died. Since 2012, it has been mine, and this year I finally took it down from the shelf. book, Dancing with the Muse in Old Age. After losing my father at age 82 to a stroke; after accompanying my mother through ten years of Alzheimer’s, stroke, and skilled-nursing care, then her death at age 86; I had pretty much decided that I’d better get things done right now, because I would be decrepit very very soon.

book, Dancing with the Muse in Old Age. After losing my father at age 82 to a stroke; after accompanying my mother through ten years of Alzheimer’s, stroke, and skilled-nursing care, then her death at age 86; I had pretty much decided that I’d better get things done right now, because I would be decrepit very very soon.