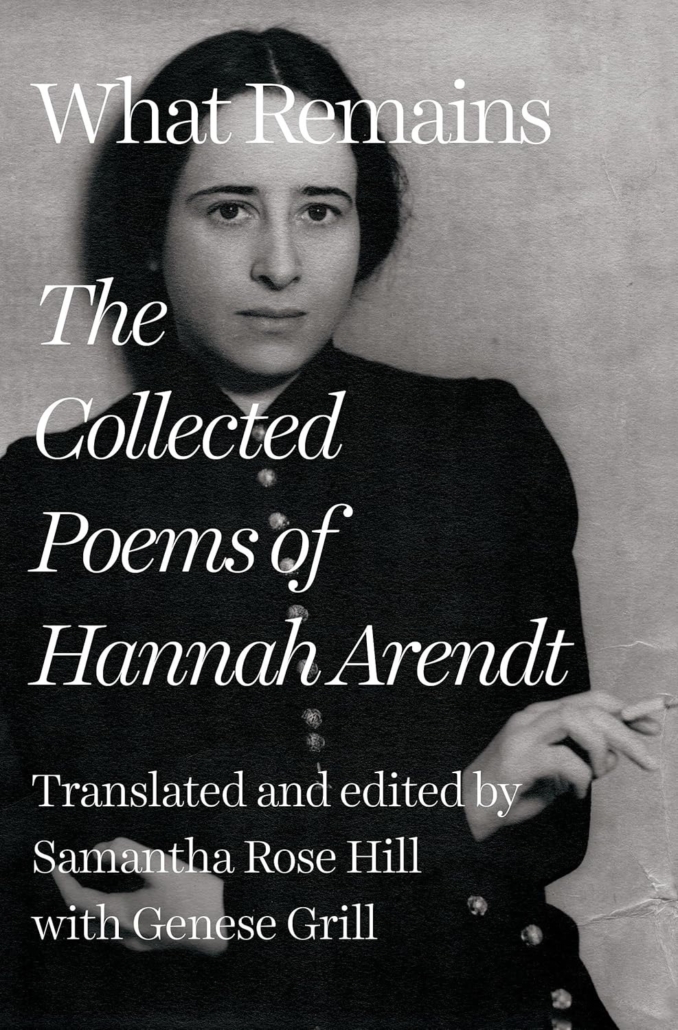

What Remains

Over the last few days, I’ve taken some very long walks, several naps, and I’ve read What Remains: The Collected Poems of Hannah Arendt, trans. and edited by  Samantha Rose Hill with Genese Grill (LiverightPubl, 2025). It is being hailed as “a landmark literary event.” The poems, presented in the original German and in English, were never intended by Arendt for publication, and they don’t strike me as being poems one memorizes or writes out in a commonplace book. They compel, however, if taken as a diary of Arendt’s life:

Samantha Rose Hill with Genese Grill (LiverightPubl, 2025). It is being hailed as “a landmark literary event.” The poems, presented in the original German and in English, were never intended by Arendt for publication, and they don’t strike me as being poems one memorizes or writes out in a commonplace book. They compel, however, if taken as a diary of Arendt’s life:

The thoughts come to me,

I’m no longer a stranger to them.

I grow into their dwelling

like a plowed field.(from Part II, 1942-1961)

If you aren’t already steeped in Hannah Arendt’s work, the footnotes and the introduction of What Remains are a necessary guide. Additionally, they offer the editors’ obsession with the poetry, and a direct look into one of the greatest minds of the 20th century.

In the introduction, Hill (a biographer of Arendt) explains that “Arendt wrote poems to record events, reflect on experiences,” but also to “engage in what she called ‘the free play of thinking.’” And it is this play of thinking that stood out to me. She was as a young woman a star student (and lover) of Martin Heidegger, but when other intellectuals embraced Naziism and Totalitarianism, she turned away in despair. I wonder to what extent her poetry kept alive her desire to be the thinker she became. Whatever the case, the paragraph describing how she carried her poems with her as she fled France, and then Europe, and came to the U. S. is worth highlighting.

As a young woman, Arendt was steeped in the German poets, and found in English writers, including W. H. Auden, Robert Lowell, Mary McCarthy, and Randall Jarrell, “her tribe.” Hill writes:

“It wasn’t that Arendt wrote poems because she was a student of poetry who was taught to write poems, or because she fancied herself a secret poet, or because she felt the muse speaking through her. Though, who is to say. Arendt wrote poems because she had found in them a language that allowed her to weave together thinking and experience.”

—Samantha Rose Hill

I am giving this book to a friend for Christmas, so in order not to mark it up I wrote many paragraphs into my morning notebook. And some of the poems found their way in, too. This line, for instance:

“We need only ignite our grief,”

If you’d like to retrace my steps, I stumbled onto this book at LitHub: https://lithub.com/snapshots-in-verse-on-hannah-arendts-long-lost-poems/

While you’re at it, look up the 2012 film, Hannah Arendt, depicting the writing of Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil, here: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hannah_Arendt_(film). I have an old blog post about seeing the film, and about writing and thinking more generally,

image from Pexels

By the way, I consider poets my tribe, too.

Whatever you celebrate at this darkest time of year, you are in my thoughts. Thank you for being here.