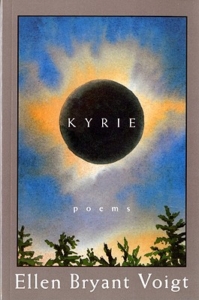

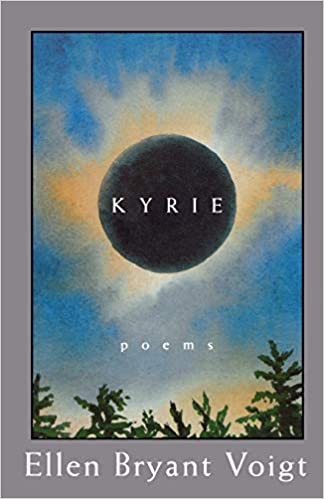

Ellen Bryant Voigt: Kyrie

KYRIE: POEMS, Ellen Bryant Voigt. W. W. Norton, 500 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10110, 1995, 80 pages, $15.95 paper, https://wwnorton.com/books.

This one really took me down the rabbit hole. By complete coincidence, it is another book of untitled sonnets, though it  couldn’t differ more from Seuss’s Frank. Well, maybe there’s a correlation in that both collections tell a dark story. Voigt is telling, however, not a personal story, but one set during the flu pandemic of 1918-1919.

couldn’t differ more from Seuss’s Frank. Well, maybe there’s a correlation in that both collections tell a dark story. Voigt is telling, however, not a personal story, but one set during the flu pandemic of 1918-1919.

If you’ve heard a choir present “Kyrie Elieson,” you know that the Greek words, translated to English, mean “Lord have mercy.” In Voigt’s merciless progression of poems we hear the voices of rural characters affected by WWI and influenza. A doctor speaks of his patients. A soldier writes home. A sister buries a sister. A mother loses a child. Whole families are wiped out. This book has been compared to Spoon River Anthology, but Voigt’s theme is the singular, unifying catastrophe of an epidemic.

And this is why Kyrie, first published in 1995, has been reclaimed by a new generation of readers. “After they closed the schools the churches closed, / stacks like pulpwood filling the morgue” begins one sonnet. Kyrie took me only an hour or so to read; perhaps you can imagine why it’s taken me most of the day to find the energy to blog about it.

Thought at first that grief had brought him down.

His wife dead, his own hand dug the grave

under a willow oak, in family ground—

he got home sick, was dead when morning came.By week’s end, his cousin who worked in town

was seized at once by fever and by chill,

left his office, walked back home at noon,

death ripening in him like a boil.Soon it was a farmer in the field—

someone’s brother, someone’s father—

left the mule in its traces and went home.

Then the mason, the miller at his wheel,

from deep in the forest, the hunter, the logger,and the sun still up everywhere in the kingdom.

—Ellen Bryant Voigt

In a Los Angeles Times review toward the end of 2020, poet Sarah Carey recounts her own discovery of and journey with these poems:

… as the United States alone approaches 400,000 projected coronavirus deaths at the end of 2020, I found myself reading Ellen Bryant Voigt’s Kyrie, her 1995 collection of sonnets that summon life during the 1918 flu pandemic. I was seeking, perhaps, a window into how others experienced an event of such life-changing proportions, and what might be learned from their stories.

Toward the end of the same review. Carey writes: “To enter the lives of the people who experienced the 1918 pandemic through the personas Voigt creates in Kyrie is to glimpse the power of collective loss and all its reverberating impacts.” Amen.

I’ll leave you with one more sonnet. Voigt is often remarked on for her musicality, but also on the simplicity and starkness of her poems, present here in both style and subject:

Who said the worst was past, who knew

such a thing? Someone writing history,

someone looking down on us

from the clouds. Down here, snow and wind:

cold blew through the clapboards,

our spring was frozen in the frozen ground.

Like the beasts in their holes,

no one stirred—if not sick

exhausted or afraid. In the village,

the doctor’s own wife died in the night

of the nineteenth, 1919.

But it was true: at the window,

every afternoon, toward the horizon,

a little more light before the darkness fell.—Ellen Bryant Voigt

The prose afterword to this book (a scant 2 pages) is also worth reading. In the final paragraph, drawing from Alfred Crosby’s America’s Forgotten Pandemic: The Influenza of 1918, Voigt writes: “In one year, one quarter of the total U. S. population contracted influenza; one out of five never recovered. Nevertheless, the national memory bears little trace.” These poems insist: remember.

Searching for the exact version of “Kyrie Eliesen” my daughters sang in high school choir (I couldn’t find it, but there are many), I discovered that the composer Stanley Grill has set selections from Voigt’s Kyrie to music. No Youtube samples (alas), but you can attempt your own Google search for the score.

To learn more about Ellen Bryant Voigt, visit The Poetry Foundation, or see the video at this site.

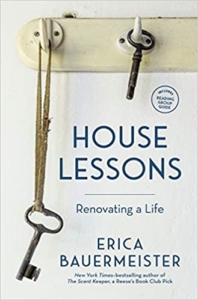

blog once a week, and what if I married these two tasks together? This is my attempt to make it so.

blog once a week, and what if I married these two tasks together? This is my attempt to make it so. In a summer when I’ve been feverishly reading doomsday accounts of what will happen to our planet because of climate change, it’s nice to imagine rescuing one house; it’s comforting to imagine how a family comes out the other end of a devastating world war and a pandemic; it’s even weirdly satisfying to imagine smashing down a wall with a sledgehammer.

In a summer when I’ve been feverishly reading doomsday accounts of what will happen to our planet because of climate change, it’s nice to imagine rescuing one house; it’s comforting to imagine how a family comes out the other end of a devastating world war and a pandemic; it’s even weirdly satisfying to imagine smashing down a wall with a sledgehammer.