Northwest Greats

When I visited Edmonds Bookshop for my reading last week, I was inspired by a couple of things. First, I am almost certain that it was something I saw there (on the website? on a poster?) suggesting I plant a northwest shrub in honor of northwesterner and writer Ivan Doig, who died on April 9. So this weekend I bought a blossoming currant. (And snapped a picture for you.)

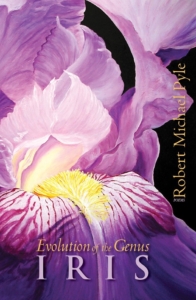

A second northwest impulse inspired by the bookshop — while browsing their poetry shelves, I found Robert Michael Pyle‘s Evolution of the Genus Iris. And even though I seriously do not need to buy any more books (!) I bought it. Here’s a poem for spring. And peace.

A second northwest impulse inspired by the bookshop — while browsing their poetry shelves, I found Robert Michael Pyle‘s Evolution of the Genus Iris. And even though I seriously do not need to buy any more books (!) I bought it. Here’s a poem for spring. And peace.

PINK PAVEMENTS

How the sidewalks flush and run

when cherries, crabs, and apples shed

their petal pelts. How exploded

blossoms soften concrete and stone.In Colorado, nights before track meets,

I walked and walked, dreaming of Olympus,

holding in the exhalations of Hopa crabs

that lined our streets. Next day, the same cold

wind that always blew my discus down too soon

would strew the streets with pale pink disks.In Cambridge, cherry blossoms daubed

the rosy fronts of colleges, scented stale

doorways of pubs. Memories of winter on harsh

fen breath stripped set fruits of flower, laid

pink silk over ancient pavements, lifting skirts

and dressing lanes in time for the May Balls.Even now, when hard spring wind unclothes

the cherries in town and crabapples thicken

the night air, I feel the blunt rim of the discus

on my fingers, the cool rim of the pint on my lips.

And I think, as yet another April whiles itself

away in war,how the pavements of Baghdad must go pink,

spattered with the petals of peaches and plums,

when the car bombs burst. How blossoms

soften exploded concrete and bone.-Robert Michael Pyle