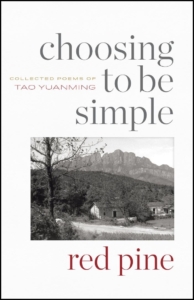

Choosing to be Simple: Collected Poems of Tao Yuanming

CHOOSING TO BE SIMPLE: COLLECTED POEMS OF TAO YUANMING, trans. Red Pine. Copper Canyon Press, Port Townsend, WA, 265 pages, $22.00, paper. https://www.coppercanyonpress.org.

Here is another book bought on impulse during one of my foraging expeditions to Edmonds Bookshop. To borrow from the Copper Canyon description:

“This bilingual collection of over 160 verses chronicles Tao Yuanming’s path from civil servant to reclusive poet during the formative Six Dynasties period (220–589). Familiar scenes like farming and contemplating the nature of work and writing are examined with intimate honesty. As Red Pine illuminates Tao Yuanming’s sensitive voice, we find the poet’s solace and sorrow in a China transformed by modernity.”

Modernity! One wonders what the poet would say about today’s world. I have been turning over that question all year, reading a few of Yuanming’s poems each morning,  copying scraps into my morning journal, and trying to imagine what to say in a blogpost.

copying scraps into my morning journal, and trying to imagine what to say in a blogpost.

Choosing to Be Simple is, simply put, irresistibly lovely. Tao Yuanming (365? 372?-427), who lived in the eastern part of China near the Yangzi River, left his employment as a civil servant around the age of 40. He chose to live simply, propagating his own food, making his own wine, and writing. The translator, also known as Bill Porter and now living in Port Townsend, embellishes Yuanming’s words with an introduction, generous footnotes, photographs, and maps (I include a photo of a page with the Chinese and Red Pine’s notes below). But the poems star:

IV [from 19: Returning to My Gardens and Fields]

I hadn’t been to the marshland for years

or enjoyed a good hike in the woods

I led my children and their cousins today

through thickets to a deserted village

we wandered around the grave mounds

and the places where people once lived

there were traces of wells and hearths

rotten bamboo and mulberry stumps

I asked a man cutting firewood

what happened to the people

he turned and said

dead or gone there’s nobody left

markets and dynasties don’t last a generation

it wasn’t an empty saying

this life is like a conjuror’s trick

when it finally ends there’s nothing there

A powerful theme throughout is Yuanming’s choice to withdraw from the world. Here, he clarifies that it was not the easier path. One imagines that a salaried position would have better pleased his wife and children, but given his larger-than-life bent toward contemplation, he could not bring himself to remain engaged in the political turmoil of his time. Think of how, in our own times, getting up each morning and turning on the television news is easier than not doing so, but it is not simpler.

Suffice to say, in note after note Red Pine explains what dynasty is being overthrown, who is murdered and replaced, what corruption prevails.

V [from Imitating the Ancients]

East of here is a man

who never has enough clothes

he eats nine meals a month

he wears the same hat ten years

no one works harder

yet he always looks happy

wanting to meet him

I left at dawn and crossed mountains and rivers

the road was hemmed in by pines

his hut was home to clouds

knowing the reason I came

he took out his zither and played

I found this book quietly powerful and I am glad it came into my hands. This morning—with rain dripping outside my cabin and the music of a flute emanating from my little CD player—I read Yuanming’s late poems, elegies for his own life, and I felt as though I had traveled over mountains and across rivers. Worth it, to spend time with Yuanming and Red Pine. I invite you to do the same.

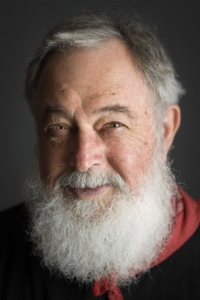

Red Pine spent many years in search of the poets he translates. You can find out more at the book page at Copper Canyon. There will be a Seattle screening of Dancing with the Dead, a documentary about Red Pine, on April 21, at SIFF Cinema Egyptian. Click on the link to learn more.

Red Pine spent many years in search of the poets he translates. You can find out more at the book page at Copper Canyon. There will be a Seattle screening of Dancing with the Dead, a documentary about Red Pine, on April 21, at SIFF Cinema Egyptian. Click on the link to learn more.

The poems in A Nail the Evening Hangs On are not those poems.

The poems in A Nail the Evening Hangs On are not those poems.

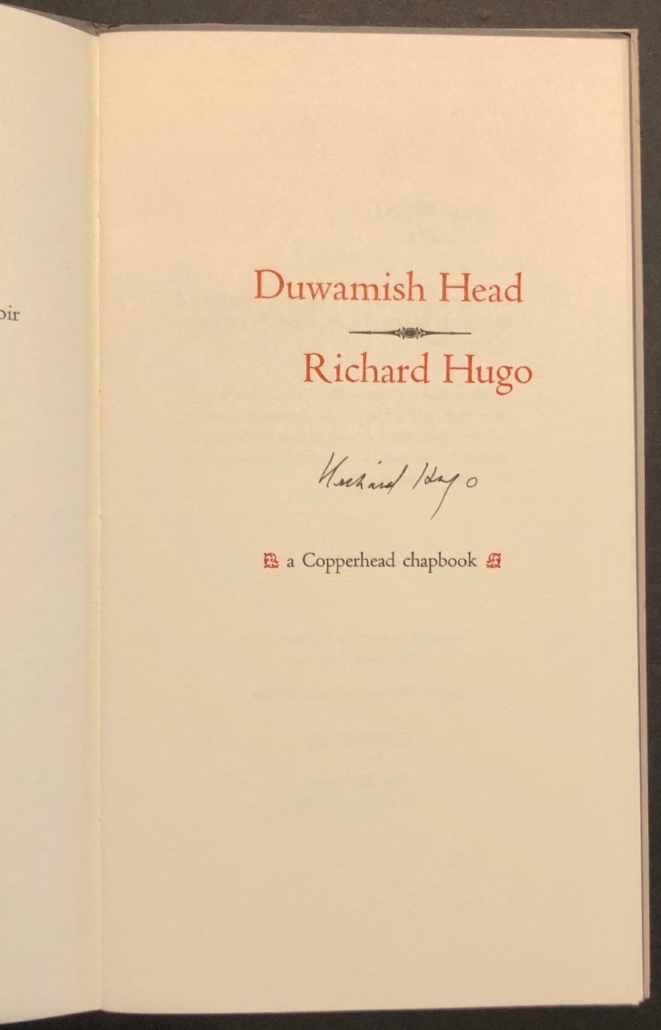

Richard Hugo, recently passed along to me by a friend who was letting go of some books. Copperhead no longer exists, and I couldn’t find any mention of it when I searched, but I suspect it was a precursor of Copper Canyon, as this chapbook was produced by Sam Hamill and Tree Swenson.

Richard Hugo, recently passed along to me by a friend who was letting go of some books. Copperhead no longer exists, and I couldn’t find any mention of it when I searched, but I suspect it was a precursor of Copper Canyon, as this chapbook was produced by Sam Hamill and Tree Swenson.