Valerie Martinez, “Rock and Marrow”

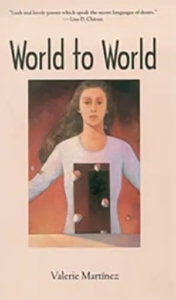

I came across VALERIE MARTÍNEZ at the Taos Summer Writers Conference, several years ago. I attended a reading,  I think, though maybe it was a panel, and I bought her book, World to World, which I have been lucky to own ever since, and will be giving away in The Big Poetry Giveaway. (See my blogpost on April 13 for more information.)

I think, though maybe it was a panel, and I bought her book, World to World, which I have been lucky to own ever since, and will be giving away in The Big Poetry Giveaway. (See my blogpost on April 13 for more information.)

Lisa D. Chavez calls these poems “lush and lovely” and notes that they “speak the secret languages of desire.” I like that, “languages,” plural. Although the poems are in English, reading them you drop through into other levels of language, like the “dark coin” of a child’s eye, or the doors that “become doors.” Here is something short, but richly evocative in exactly that way. You may also notice that with the “you” of the sixth line, and the directive of the sentence after, it becomes an instruction poem.

ROCK AND MARROW

Yes, yes, the inside of morning

is cheekbone, elbow, pelvis.

Elsewhere, as the chlorophyll shrinks

earthward, so does the steady rain.

I imagine the center of the planet

hot and colorful. You see,

it needn’t always be vivid and visible.

Lie low in this monochrome

tangle of limbs. I like it

vague and warm at the center

of the densest of things.–Valerie Martinez (from World to World)

“Keeping Quiet” by

“Keeping Quiet” by