Sandra Noel, WHAT THE PAIN LEFT

WHAT THE PAIN LEFT, Sandra Noel. Kelsay Books, 502 South 1040 East, A-119, American Fork, Utah 84003, 2024, 56 pages, $20 paper, Kelsaybooks.com.

Although it is always a pleasure to read poems by Vashon Island poet Sandra Noel, this book felt very different from the two I have previously reviewed, Hawk Land (2022) and The Gypsy in My Kitchen (2015). Dedicated to her husband, who died in 2022, What the Pain Left is painted from a different palette. Though crafted with Noel’s eye for detail, her heart for nature, here the “commotion / of silver-scaled abundance / falling from nets” in “Love and Marriage,” feels doomed from the start. In “We Speak About Death Over Burgers and Fries.” I was amazed at Noel’s poise in navigating the trajectory of this book, encompassing a 40-year history: courtship to death and out the other side, alone.

I will catch you

or we will fall together

maybe there is another level

in this warren

a way out of the labyrinth.end lines from “Down the Rabbit Hole”

Of course there is no other way out of life, and perhaps that’s why the poems are often spare, more spare than I’ve  noticed in Noel’s previous books. They are tender with feeling, and accessible; for the most part, Noel omits punctuation, placing together lines about a heron abruptly with “tragedies / float noisily by” (“In the Shadows”). Unexpected capital letters intrude, and exclamation marks. All of which seem to be insisting on making sense of what feels senseless, an illness, ineffectual treatment, and untimely death. This praise from the back cover, felt apt:

noticed in Noel’s previous books. They are tender with feeling, and accessible; for the most part, Noel omits punctuation, placing together lines about a heron abruptly with “tragedies / float noisily by” (“In the Shadows”). Unexpected capital letters intrude, and exclamation marks. All of which seem to be insisting on making sense of what feels senseless, an illness, ineffectual treatment, and untimely death. This praise from the back cover, felt apt:

Part diary, part love letter, Noel’s humor, gratitude, and self-awareness keep these poems honest and truly from the heart. –Katy E. Ellis

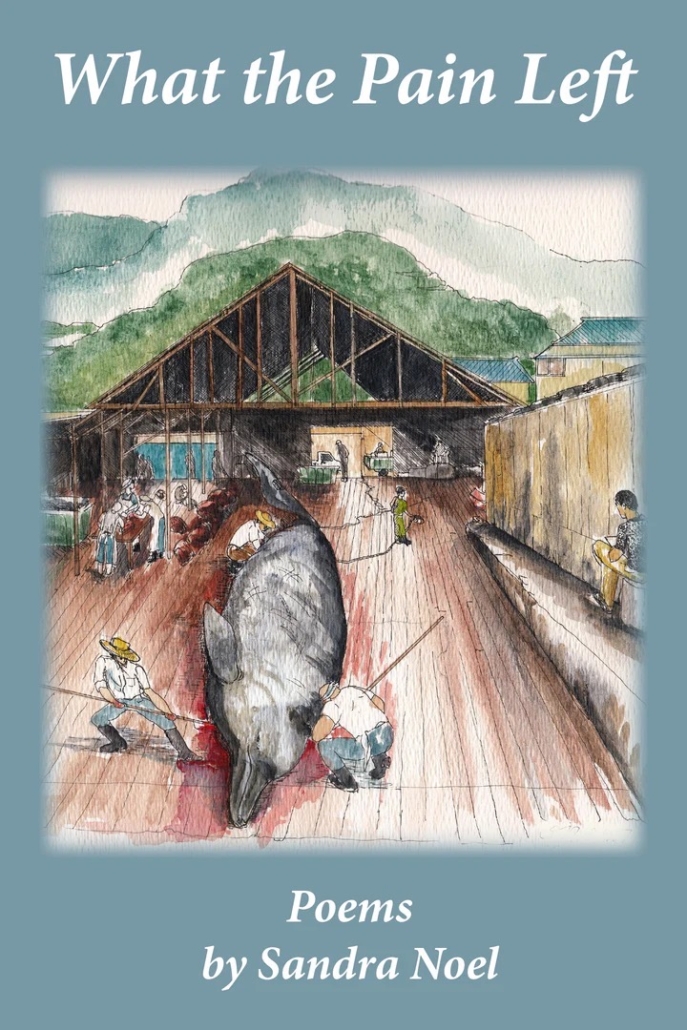

The cover art is by Sandra Noel, herself, a watercolor painting of Gaibo Whaling Station, Wadaura, Chiba Prefecture, Japan. In the poem, “Love and Marriage,” the whaling station provides a metaphor—at least, so I thought—for the messiness of life:

Love and Marriage

Every morning

we walked to the whaling station

bought hot sweet coffee in cans

from a machine on the street

too early for the sun but not the market

as vendors shoveled crushed ice

into large blue bins

and elegant fishing boats glided

alongside the dock

their holds full and ready to disgorge.As we sipped our coffee

arm in arm

I listened to the talk of local women

understanding nothing

and everything as women do.Then I saw your sea blue eyes

bright with promise

the same way you looked at me

gazing over that commotion

of silver-scaled abundance

falling from nets onto the dock

into the waiting bins of ice

and hopeful buyers with their yen

fish sorted from fish

squid, octopus, sea squirts

and smaller, even stranger creatures.You pushed me forward

when the crowd thinned out

kneeling, picked up wriggling globs

telling me their scientific names

as my eyes wandered to seabirds

frenzied by the blood and entrails

where women cleaned fish in seawater

then, over your beautiful shoulders

to the sea, bright blue

the great Eastern Sun slowly rising

turning the bay into liquid gold.“Are you listening to me!?”

“Yes,” I said, “Yes of course!”

and when I think of that first lie

I remember all the others

the kind that make a marriage work

but destroy a love affair.—Sandra Noel

Notice how the lack of punctuation makes some lines ambiguous. Is it the local women who understand nothing, as women do? or is it the I, listening, who understands nothing? The latter interpretation makes, “Then I saw your sea blue eyes” a kind of homecoming, a moment of pure understanding. That the poem’s ending feels unresolved, or imperfectly resolved (going on a couple beats too long, or cut short?), is a simulacrum of a life ended too soon, and part of what makes this collection of poems so moving.

You can learn more by visiting Noel’s website, Noel Design. Or visit her book page at Kelsay Books.

$16.99, paper,

$16.99, paper,  If the poems feel at times brutal, they are brutally honest. They are also, as Karen Whalley points out in her appreciation of this book, “At their core, love poems,” “almost apologetic that [her husband] must be both witness and participant to her dying.” Her husband is an important character here. Consider the prose-poem, “Letter She Wrote Him,” where Albiso concludes, “Stars here, the sky a great camp with its fires lit, and daily the winter wren serenades, body turned to plea. Do you know the origin of mercy? From the Latin merces—the price paid for something.”

If the poems feel at times brutal, they are brutally honest. They are also, as Karen Whalley points out in her appreciation of this book, “At their core, love poems,” “almost apologetic that [her husband] must be both witness and participant to her dying.” Her husband is an important character here. Consider the prose-poem, “Letter She Wrote Him,” where Albiso concludes, “Stars here, the sky a great camp with its fires lit, and daily the winter wren serenades, body turned to plea. Do you know the origin of mercy? From the Latin merces—the price paid for something.”