J. I. Kleinberg, DESIRE’S AUTHORITY

DESIRE’S AUTHORITY, J. I. Kleinberg, from Triple No. 23. Ravenna Press, Edmonds, Washington, 2023, pp. 61-80, paper, $12.95. http://ravennapress.com.

Last Saturday, I slipped away from the Chuckanut Writers Conference to attend a reading, at Dakota Art in downtown Bellingham, featuring Anita K. Boyle, Sheila Sondik, and J. I. Kleinberg. Yes, the conference was wonderful, with a plethora of good stuff on offer, but the trifecta of these voices, plus their art, was too great a temptation. I’m so glad I was able to be there.

Kleinberg read from several books, including her Dickinson inspired chapbook of collage poems, Desire’s Authority, published last year by Ravenna Press. I’ve been on a book-buying binge (a binge that seriously has to stop) but this book I already had in my possession. So, once I was home, I went through my TBR pile of poetry books and found it.

Take all the serendipity of how I stumbled into this happy accident, and times it by three, and you have Triple No. 23  (also featuring chapbooks by Michelle Eames and Heikki Huotari).

(also featuring chapbooks by Michelle Eames and Heikki Huotari).

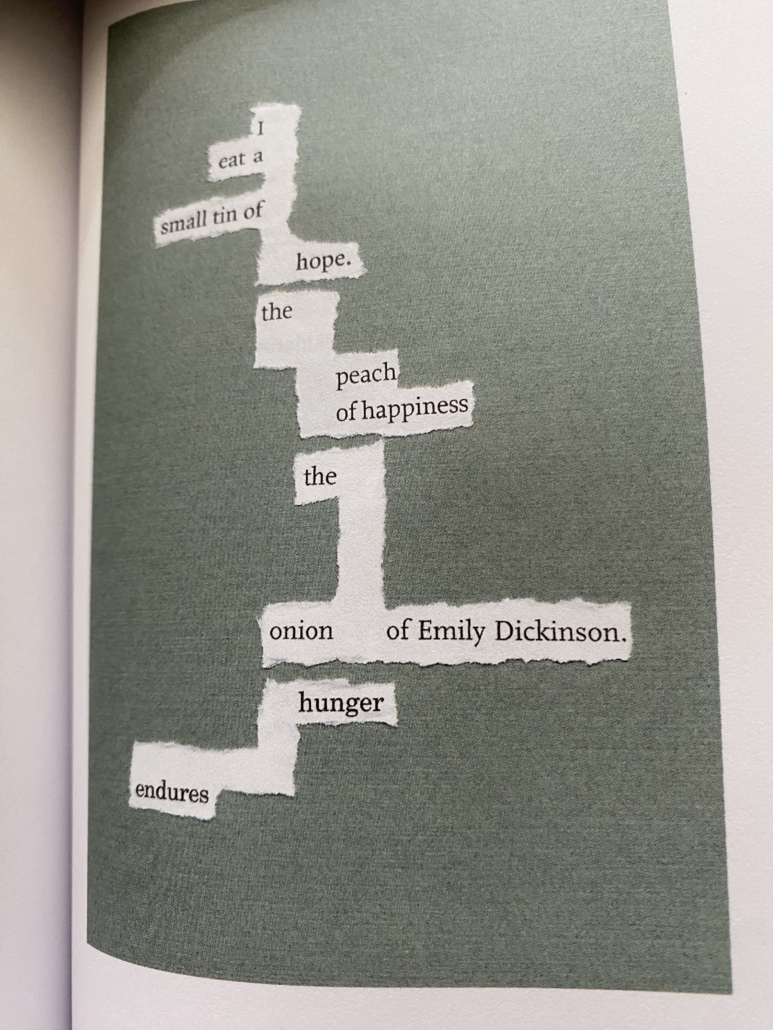

Kleinberg’s collage poems, alone, are all about serendipity, juxtaposition, and happy accidents. She creates them by cutting apart words found in magazines—if it sounds a bit like ransom demands, you’re not wrong. Not demanding in the sense of difficulty, but definitely willing to hold your attention hostage. In the author’s note Kleinberg reveals how she came up with her collage series (which is extensive, and not only this set of poems):

Through the accident of magazine page design, unrelated words fell into proximity to cast unintended meaning across the boundaries of sentence, paragraph, and column break. Leaving behind the words’ original sense and syntax, I collected these contiguous fragments of text, each roughly the equivalent of a poetic line. Arrayed on my worktable, they began to talk with one another and assume a new shape of visual poems. —J. I. Kleinberg (p. 89)

Gaps, fragments, the hop from one word or phrase to the next like hopping stone to stone across a creek, the occasional precarious drop—these found poems are a visual and poetic delight. I can’t decide on a water metaphor or fire to best describe them. Either way, I love these poems in part for how they invite a reader’s imagination into their creation. If there’s sometimes a little groping to find a shutter or door to throw open, a match to light, the illumination comes.

You can learn more about Kleinberg’s collage poems—and see examples—at her blog, Chocolate Is a Verb. She is also the curator of The Poetry Department, which delivers one poetry event, quotation, or other enticing poetry-related discovery every day.

borrowed from Judy’s blog, a photo from the exhibit, “Ink, Paper, Scissors: nature speaks in three voices”

![]()

Although I have looked her up (and you can, too, beginning at

Although I have looked her up (and you can, too, beginning at

2019, 80 pages, $16 paper,

2019, 80 pages, $16 paper,