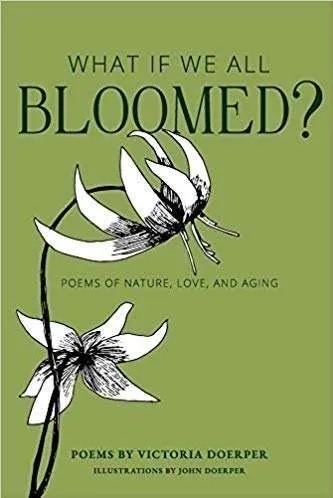

Victoria Doerper, WHAT IF WE ALL BLOOMED?

WHAT IF WE ALL BLOOMED? POEMS OF NATURE, LOVE, AND AGING, Victoria Doerper. Penchant Press International, Bellingham, WA, 2019, 94 pages, paper, $15.95.

What If We All Bloomed? is a perfect title for this book of meditative poems. Here’s a poet who can celebrate  marriage in one poem, and claim kinship with frogs in the next. Another riffs off Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “Pied Beauty,” beginning, “Praise God for damaged things.” Yes, life is messy, Doerper proclaims here, then offers praise “For mismatched mates and misdirected mail, / For bulbs of scarlet tulips, rising in a golden bloom, / For spackled spark of beauty in tender broken things…” It made me want to grab my pen and write my own poem for what’s broken.

marriage in one poem, and claim kinship with frogs in the next. Another riffs off Gerard Manley Hopkins’ “Pied Beauty,” beginning, “Praise God for damaged things.” Yes, life is messy, Doerper proclaims here, then offers praise “For mismatched mates and misdirected mail, / For bulbs of scarlet tulips, rising in a golden bloom, / For spackled spark of beauty in tender broken things…” It made me want to grab my pen and write my own poem for what’s broken.

Last week I began reading Pema Chodron’s When Things Fall Apart, but stopped when I came to this line at the end of the Introduction, a quote from her teacher, Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche:

“Chaos should be regarded as extremely good news.”

Doerper’s poems encouraged me to return to Chodron, to muster at least some willingness to sit with all that is swirling inside me, to consider bringing it back with me “to the path” (Chodron, xiii).

Meanwhile, reading poems (and walking) are keeping me alive.

Hedgerows

I’m convinced that heaven

Lurks in old hedgerows,

Not like a predator, but

More like a mystery

Laced through thickets

Tangled with song.

In those byzantine temples

Of leafy, shaggy, profligate

Bud, flower, and berried

Commonplace delight,

Visited by visions of roses

Wafting the incense of attar

Into the sacred air,

Where angels shelter

The hungry, the trod-upon,

The sky-travelers seeking rest,

No questions asked,

No proof of worthiness,

No papers required

For an offer of ground

In an unsullied place

Filled with the potent

Possibility of grace.—Victoria Doerper

That “possibility of grace” is, I think, what Chodron is talking about, too.

What If We All Bloomed? is dedicated to John Doerper, the poet’s husband, who also did the lovely drawings illustrating the cover and throughout the book.

The website for Penchant International didn’t work, but I found Doerper’s book for sale at Sidekick Press, and it is also available at Village Books ($1 shipping). Chodron’s When Things Fall Apart: Heart Advice for Difficult Times is widely available.

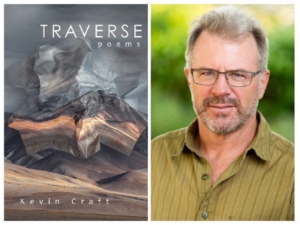

Triple as 3 chapbooks). I posted a photograph on Instagram of each cover with the day’s number, with the exception of this book. (For day 13, I posted another cover a second time.)

Triple as 3 chapbooks). I posted a photograph on Instagram of each cover with the day’s number, with the exception of this book. (For day 13, I posted another cover a second time.)