If you follow my blog, then you already know that I read a lot of books. I love sharing my books with friends and passing them along to the exact right person. But every so often, I come across a book that is so wonderful, I want to buy copies for all my friends.

One of those books is THE CIRCLE, by Laura Day.

Laura Day has written a number of successful books, including PRACTICAL INTUITION, WELCOME TO YOUR CRISIS, and HOW TO RULE THE WORLD FROM YOUR COUCH. But THE CIRCLE is my go-to favorite. I’ve read it several times, and I think I have an effective, “anti-woo woo” way to share it with you.

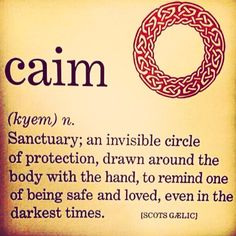

To my mind, THE CIRCLE isn’t necessarily “woo woo” (what do we mean by that? Spiritual? And what would be wrong with spiritual?), unless you want it to be. In the Prologue, Day reassures readers that The Circle is “not in conflict with any religious or spiritual beliefs,” and my experience has borne this out. You could understand it as an Irish Caim, a blessing circle. But it is not magic, and it is not about any realm of being other than the one we live in right now.

To my mind, THE CIRCLE isn’t necessarily “woo woo” (what do we mean by that? Spiritual? And what would be wrong with spiritual?), unless you want it to be. In the Prologue, Day reassures readers that The Circle is “not in conflict with any religious or spiritual beliefs,” and my experience has borne this out. You could understand it as an Irish Caim, a blessing circle. But it is not magic, and it is not about any realm of being other than the one we live in right now.

As Day explains, you have probably walked the circle before. My most powerful past experience of it came when my husband, Bruce, had a major health crisis. He was already in the hospital, and had undergone successful surgery. It was Mother’s Day and our daughters were 8, 8, and 2. My parents had been helping out, and planned to go home later that day, as Bruce was scheduled to be released. I had everything under control (hah!)—I had even worked out my teaching schedule so that I would miss only one day of classes! Long story short, my mother got up that Sunday morning and cancelled everything I had orchestrated for my Mother’s Day. She told me that I was to go to the hospital, by myself, and see Bruce.

Long story short, the supervising nurse met me as I got out of the elevator. My husband was hallucinating, he had ripped out his stitches and his catheter, and done some other damage to himself, and he was headed back into surgery.

If I wanted this introduction to be twice as long, I could tell you the astounding number of coincidences (besides my mother’s initial insight) that then ensued–including a woman I scarcely knew showing up at the hospital to take me to lunch because it was Mother’s Day and she thought it would be nice to do something for me. For the next ten days, I lived inside a circle where the right conversations, unexpected help, and loving encouragement flowed to me.

Here’s how Laura Day has helped me to understand this personal story.

Sometimes, often in a crisis, we get intensely focused on what we need. It’s kind of like the way radio waves are all around us, all the time, but we don’t always have a receiver tuned in to them. When my husband had his health crisis, I tuned in.

THE CIRCLE is about creativity; specifically, it is about living and creating consciously. And it can help you to tune in to what you

really really really want to create in your life.

Day has divided the journey into nine parts, with three main headings: Initiation, Apprenticeship, and Mastery. My favorite subsections might be ritual and synchronicity, and these are the parts I always incorporate into my own classes, even my intro-to-composition classes that I used to teach at my college. (Now, of course, I’m sharing all of it!)

I hope I’ve intrigued you with this introduction. Over the next several weeks I’ll be writing my way through The Circle and I’d love it if you could join me.

Of course I recommend purchasing Laura’s book, but the posts will be enough to move you all the way through what I am calling WRITING THE CIRCLE.

In order to get started, all you have to do is subscribe to my blog. (See the link below.) If you want to know a little more, three of the posts will be available on the blog to everyone, and you can read the first one by clicking here.

To my mind, THE CIRCLE isn’t necessarily “woo woo” (what do we mean by that? Spiritual? And what would be wrong with spiritual?), unless you want it to be. In the Prologue, Day reassures readers that The Circle is “not in conflict with any religious or spiritual beliefs,” and my experience has borne this out. You could understand it as an Irish Caim, a blessing circle. But it is not magic, and it is not about any realm of being other than the one we live in right now.

To my mind, THE CIRCLE isn’t necessarily “woo woo” (what do we mean by that? Spiritual? And what would be wrong with spiritual?), unless you want it to be. In the Prologue, Day reassures readers that The Circle is “not in conflict with any religious or spiritual beliefs,” and my experience has borne this out. You could understand it as an Irish Caim, a blessing circle. But it is not magic, and it is not about any realm of being other than the one we live in right now.