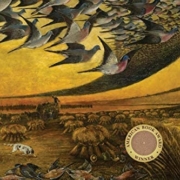

It’s Earth Day, and this morning I spent my early hours rereading Passings, 15 poems about extinct birds—a  luminous, heartbreaking, award-winning collection of poems from Holly J. Hughes.

luminous, heartbreaking, award-winning collection of poems from Holly J. Hughes.

Passings was first published in 2016 by Expedition Press as a limited-edition letterpress chapbook. It garnered national attention in 2017 when it received an American Book Award from The Before Columbus Foundation. As Holly says in her acknowledgments, “fitting that a small letterpress, itself an endangered art form, would be honored.” More than fitting, richly deserved.

It is our great good fortune that in 2019 Passings was reprinted by Jill McCabe Johnson’s Wandering Aengus Press. Although the gratitudes are slightly expanded, it is essentially the same and available from the press, or your independent bookstore.

When I contacted Holly, she wrote back with these words—and it’s impossible for me to excerpt or condense them. Consider this essay, and the poem following, her Earth Day gift to all of us.

Listening Hard for All the Voices: Writing Passings

Sometimes we don’t have a choice. Each time I tell this story I remember that moment coming down the stairs of my cabin and seeing the Audubon painting of the passenger pigeon I’d just hung on the wall. The dusky-blue plumage and russet breast glow eerily in a stray shaft of morning sun, and the pair of birds caught by Audubon seem alive, inviting me to enter their intimate moment together. I’m not sure how long I stood there watching; at some point I heard a voice say: Write about us. You know. What happened. Yes, I did know, but I wasn’t sure I could. It was painful to contemplate writing about the slaughter of those vast flocks of passenger pigeons that filled the skies like a great storm back in the early 1900s. But the chance glimpse of their ghost spirits that morning felt like an invitation I couldn’t refuse.

That was the first poem in Passings.

Now they need company, I thought, and of course, there is no shortage of species of birds that have gone extinct, the list a heart-wrenching litany. As I researched each bird, I dug down through the sobering, overwhelming statistics for firsthand accounts, for stories that would bring each bird to life on the page, details that would allow us to see each departed bird in all its fleeting, fragile, idiosyncratic beauty.

I’m not sure when I knew I had a collection, but at some point, the project took on a life of its own. As the poems stacked up, the stories of how each species met its end began to repeat, became depressingly familiar: slaughter for feathers, for meat, for sport, for revenge; habitat loss, rats plundering nests. The list went on and on. I had written close to thirty poems when I realized I would choose only fifteen to include, no more, for that might be all we could bear. That decision allowed me to finish the collection. That and a book called Swift as a Shadow: Extinct & Endangered Birds, by photographer Rosamond Purcell, whose haunting portraits of extinct birds reminded me not to turn away.

This morning, as I write this, I’ve just returned from my morning walk listening to the shrieks of an osprey and eagle as they circle high above my cabin. While I watch, the eagle dive-bombs the osprey, who deftly somersaults, then regains balance, her wings flashing light as they catch the morning sun, this moment held briefly aloft. Eventually, the osprey returns to her nest in a tall snag down the street where I hope a young one waits. I’m not sure this is connected, but I think it has to do with being willing to listen hard for all the voices, past and present, and to make space for the silenced voices, too. If not the poets and artists, who will do this?

“Passenger Pigeon” is the first poem in Passings, and you can follow this link to listen to a choral presentation of it, performed by The Crossing Choir.

PASSENGER PIGEON

Echtopistes migratorius

— from the painting by James J. Audubon, 1824. On Sept. 1, 1914,

Martha, the last passenger pigeon died in the Cincinnati Zoo.

See how she bends to him, her beak held within his

while she waits for his food to rise up to her hunger.

He rests on the arcing branch, his neck a perfect answer to hers,

wings held aloft and slightly splayed while long tail feathers stream

away, Prussian blue going to dusk, breast russet, branch below

studded with viridian lichen to match his coat, colors chosen

by Audubon as he painted them in courtship in situ.

See how her colors foreshadow the fall—dun, mustard, black—

how her tail balances his wings painted in parallel planes,

how the drooping oak leaf holds them in place, stasis

in which they are aware of no one but each other.

Audubon captured them in gouache, graphite, and pastels,

not knowing they would soon be gone; in his time

they were more numerous than all other species combined.

They say the pigeons flew over the banks of the Ohio River

for three days in succession, sounding like a hard gale at sea.

Years later, guns splattered shot into skies stormy with pigeons.

Thousands plummeted, filling railroad cars bound for fine restaurants.

Now, of those hundreds of millions that once darkened

the skies, we are left with Martha, who never lived in the wild,

stuffed in the Smithsonian, Prussian blue feathers stiff,

glass eyes staring, waiting, still, for her mate.

—Holly Hughes

“Carolina Parakeet” also has a choral piece and this great painting by Audubon (see below). As a final note, let me add this direction, from the notes: “What You Can Do to Help Protect Birds,” climate.audubon.org.

constraint which requires that a poet not use a certain letter of the alphabet. Using words starting with “B” as the title of each poem, the poems themselves, written as lyrical, lovely dictionary entries, exclude it.

constraint which requires that a poet not use a certain letter of the alphabet. Using words starting with “B” as the title of each poem, the poems themselves, written as lyrical, lovely dictionary entries, exclude it.

mean they are curious. They ask questions of the world” (back cover, and on Wong’s website). I’ve always liked poems that take risks, and I love unexpected catalogues of details. Jane Wong has a gift for this: “Two arms crossed between two tables / My heart crossed between my eyes, out of focus / In January, I looked for winter underneath potted plants / But I found my brother instead” (from “And the Place Was Matter”). There is a story here, but like an abstract painting, the poems refuse to tell the story in an autobiographical, linear way. It’s haunting, haunted by a brother and mother, by ghosts in China. I’m intrigued with how Jane weaves what seems like the world I occupy (too) together with something far more surreal and surprising: “At twenty, I halved caution / and called it Jane” (from “Twenty-four”). I often imagine discussing a poem with a class, and I can’t even imagine what my freshman and sophomore college students would have said about this. It defies explanation, invites an explosion of imagination.

mean they are curious. They ask questions of the world” (back cover, and on Wong’s website). I’ve always liked poems that take risks, and I love unexpected catalogues of details. Jane Wong has a gift for this: “Two arms crossed between two tables / My heart crossed between my eyes, out of focus / In January, I looked for winter underneath potted plants / But I found my brother instead” (from “And the Place Was Matter”). There is a story here, but like an abstract painting, the poems refuse to tell the story in an autobiographical, linear way. It’s haunting, haunted by a brother and mother, by ghosts in China. I’m intrigued with how Jane weaves what seems like the world I occupy (too) together with something far more surreal and surprising: “At twenty, I halved caution / and called it Jane” (from “Twenty-four”). I often imagine discussing a poem with a class, and I can’t even imagine what my freshman and sophomore college students would have said about this. It defies explanation, invites an explosion of imagination.

luminous, heartbreaking, award-winning collection of poems from

luminous, heartbreaking, award-winning collection of poems from

editor of The Nation, his poems have appeared all over the place, including The New Yorker, which I read faithfully (or thought I did), teaches all over the place, and founded

editor of The Nation, his poems have appeared all over the place, including The New Yorker, which I read faithfully (or thought I did), teaches all over the place, and founded