The Autumn Equinox

Tomorrow — at 12:21 p.m., in my area at least — autumn begins. It seems an excellent time to write a fall poem. Here’s one that I’ve cribbed from the collection at https://www.poetryfoundation.org.

For the Chipmunk in My Yard

BY ROBERT GIBB

I think he knows I’m alive, having come downThe three steps of the back porchAnd given me a good once over. All afternoonHe’s been moving back and forth,Gathering odd bits of walnut shells and twigs,While all about him the great fields tumbleTo the blades of the thresher. He’s luckyTo be where he is, wild with all that happens.He’s lucky he’s not one of the shadowsLiving in the blond heart of the wheat.This autumn when trees bolt, dark with the firesOf starlight, he’ll curl among their roots,Wanting nothing but the slow burn of matterOn which he fastens like a small, brown flame.

I am still reading Ursula K. Le Guin’s Words Are My Matter — an essay each week or so — and I just came across “The Beast in the Book.” She got me thinking about animals and how we share the world with them, not very politely, and how rich children’s literature is with animals. As Le Guin puts it:

The general purpose of a myth is to tell us who we are — who we are as a people. Mythic narrative affirms our community and our responsibilities, and is told in the form of teaching-stories both to children and adults.

–Ursula K. Le Guin

Le Guin doesn’t find it at all curious that children learn to read by sounding out the words in “Peter Rabbit,” or that they weep over Black Beauty. She finds it a shame that as we grow older we lose our facility to identify with animals. I loved this paragraph, about T. H. White’s The Sword in the Stone:

Merlyn undertakes Arthur’s education, which consists mostly of being turned into animals. Here we meet the great mythic theme of Transformation, which is a central act of shamanism, though Merlyn doesn’t make any fuss about it. The boy becomes a fish, a hawk, a snake, an owl, and a badger. He participates, at thirty years per minute, in the sentience of trees, and then, at two million years per second, in the sentience of stones. All these scenes of participation in nonhuman being are funny, vivid, startling, and wise.

–Ursula K. Le Guin

I think it’s that “sentience of trees” that really made that paragraph stick for me, as I’ve also been reading Peter Wohlleben’s The Hidden Life of Trees.

My challenge for you this week is to write an autumn poem about some living being in your backyard or near environs. Like Robert Gibb’s chipmunk, how does this creature, with its small flame of wildness, teach you to be alive?

https://wdfw.wa.gov/species-habitats/species/tamiasciurus-douglasii

I don’t have chipmunks in my backyard, but we do have the small brown Douglas squirrels and the invasive, bigger gray squirrels. We sometimes have possums and raccoons; more rarely we’ve sighted deer and coyotes. Always, there are the birds: flickers, juncos, towhees, Stellar’s jays, flocks of crows each dusk. Last week, on a late walk with my dog, Pabu, I watched a flock of geese pass over, honking. The other day, my husband saw what he swears was a merlin, which is as good a sign of the changing season as any.

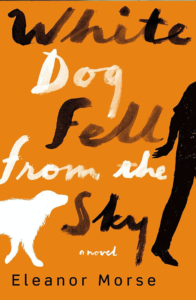

These past few months I have been on a reading binge — dozens of mystery novels, of course, and tons of poetry. But I just finished reading a novel, White Dog Fell from the Sky, by

These past few months I have been on a reading binge — dozens of mystery novels, of course, and tons of poetry. But I just finished reading a novel, White Dog Fell from the Sky, by

blog once a week, and what if I married these two tasks together? This is my attempt to make it so.

blog once a week, and what if I married these two tasks together? This is my attempt to make it so. In a summer when I’ve been feverishly reading doomsday accounts of what will happen to our planet because of climate change, it’s nice to imagine rescuing one house; it’s comforting to imagine how a family comes out the other end of a devastating world war and a pandemic; it’s even weirdly satisfying to imagine smashing down a wall with a sledgehammer.

In a summer when I’ve been feverishly reading doomsday accounts of what will happen to our planet because of climate change, it’s nice to imagine rescuing one house; it’s comforting to imagine how a family comes out the other end of a devastating world war and a pandemic; it’s even weirdly satisfying to imagine smashing down a wall with a sledgehammer.