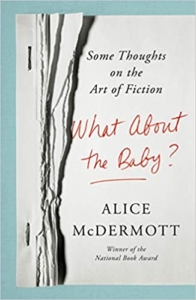

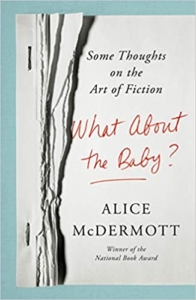

If you are still wondering what to buy the fiction-writer on your Christmas list, I am happy to recommend Alice McDermott’s What about the Baby?: Some Thoughts on the Art of Fiction (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021).

If you are still wondering what to buy the fiction-writer on your Christmas list, I am happy to recommend Alice McDermott’s What about the Baby?: Some Thoughts on the Art of Fiction (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2021).

McDermott’s 2013 novel, Someone, is one of my favorite novels of all time. At some point I decided that where McDermott leads, I will follow, and I snapped up her craft book in hardback the minute it was published. For a few months, I was happy simply to own the book. But now that I’m finally reading it, it’s proved a great way for me to procrastinate getting my poetry book finished and my mystery novel revised. A series of lectures given at the Sewanee Writers’ Conference over a twenty-year period, What about the Baby? is utterly brilliant, chockablock with gems about stories, sentences, and faith.

Because in my writers group we often debate whether to cut a word or not, I wanted to share this passage, which is not McDermott but E. B. White of Strunk & White’s The Elements of Style. We all know his famous advice to “omit needless words,” but I don’t think I had read this elaboration that White, himself, offered a reader who objected:

It comes down to the meaning of “needless.” Often a word can be removed without destroying the structure of a sentence, but that does not necessarily mean that the word is needless or that the sentence has gained by its removal.

If you were to put a narrow construction on the word “needless,” you would have to remove thousands of words from Shakespeare, who seldom said anything in six words that could be said in twenty.

Writing is not an exercise in excision; it’s a journey into sound. How about “tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow”? One “tomorrow” would suffice, but it’s the other two that have made the thing immortal. (E. B. White, qtd on pp. 62-63)

McDermott surrounds this with her own notions about style, for instance about sound: “read your sentences out loud in order to discover your own sound: the rhythm, pattern, refrain, reprise of your prose” (63).

…of your prose, and your poetry.

If you are still wondering what to buy the fiction-writer on your Christmas list, I am happy to recommend Alice McDermott’s

If you are still wondering what to buy the fiction-writer on your Christmas list, I am happy to recommend Alice McDermott’s

So, about a week ago I thought I would write a blogpost inspired by Steven Pressfield, about…pain. I copied Pressfield’s recent post and linked it (see bottom of page), and I added this passage from the painter Grant Wood:

It’s all very wise and was meant to encourage me to push through a rough patch. But it really just made me feel the complete opposite of encouraged. I wanted to go back to bed.

On a whim I googled “DELIGHT,” and it took me straight to J. B. Priestley’s book Delight, published in 1949. Not long ago my husband and I watched the 2018 film of Priestley’s play, An Inspector Calls, so this seemed like one of those synchronicities that we ought to pay attention to. I bought the book, downloaded it, and, well, was delighted.

In the preface, Priestley begins, “I have always been a grumbler.” He goes on to explain the benefits (the delights?) of a good grumble. But then we get 114 short chapters on what delights him: reading detective stories in bed, lighthouses, waking to the smell of bacon, the ironic principle, orchestras tuning up, making stew, departing guests. Some of it is a little dated (the stereoscope, wearing long trousers, and several chapters about the delights of smoking). But it’s also a window into Priestley’s time (1894-1984), bits of a lost world.

I’m rushing off to a task this morning (and finishing it will delight me), but here’s a post from another blog that does a better job than I have time for: https://www.stuckinabook.com/delight-jb-priestley/

And that’s your assignment for this week. Sure, I hope you sometimes push through, dig deep, suffer for your art, but meanwhile: what delights you? I’d love to hear about it.