Here in my neighborhood north of Seattle, Washington, we have had our second snowfall of the year—about three inches yesterday and the evening before. Today, it’s 27 degrees (low of 19!) and the sun is shining. Outside my window: glittering white.

On December 1st, despite slush and ice, I set out for a long afternoon walk, and I slipped on a patch of ice, fell hard, and  cracked the head of my left radius bone, right up there in my elbow. I was in a fiberglass splint—looked like and felt like a big ol’ cast—for 7 days. The initial evaluation suggested the crack went all the way through. I couldn’t use my arm, I couldn’t get it wet, couldn’t practice my Christmas songs on the piano, couldn’t wear my Christmas sweaters. I couldn’t type! It took me four or five days just to figure out how to wear clothes and leave the house.

cracked the head of my left radius bone, right up there in my elbow. I was in a fiberglass splint—looked like and felt like a big ol’ cast—for 7 days. The initial evaluation suggested the crack went all the way through. I couldn’t use my arm, I couldn’t get it wet, couldn’t practice my Christmas songs on the piano, couldn’t wear my Christmas sweaters. I couldn’t type! It took me four or five days just to figure out how to wear clothes and leave the house.

I saw the orthopedic surgeon on day seven, expecting to be told I’d need surgery. Instead, he said the crack was partial, and “No surgery,” plus—amazing grace—no cast! In his opinion the crack would heal just fine if I didn’t lift, push, or pull with my left arm, or fall down again. He showed me how a single week of having the arm in the splint had weakened my grip, and compromised my ability to move my wrist or do simple things like touch my head. (Try flossing your teeth when you have only one arm.) “That’s not from the break; that’s from having your arm immobilized. If you wear a cast for six or eight weeks, you’ll need physical therapy for a year!”

He said I could do “light kitchen work” and—more important—“you can type.”

I admit to having entirely lost my Christmas spirit. I’m only now getting it back. Partially.

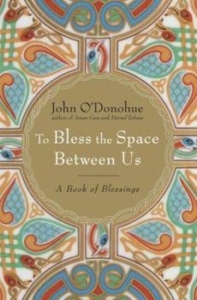

Nonetheless, over the last few weeks I have been co-leader of an Advent study at my church. I committed to it in October, after all, and my primary role in the group is merely to bring poems. Easy peasy. I’ve collected both traditional Advent poems by well-known Christian writers such as Madeleine L’Engle and Oscar Romero, and poems that might not spring to mind when we’re talking about Bethlehem, gentle donkeys, shepherds guarding their flocks by night, and the birth of a savior in a stable.

Not that such poems can’t be wonderful. (Of course they are.) I guess what I’ve been after is to broaden our context, to make us see the Advent season in the light of our own lives.

Advent first began in the 4th century as a period of penance for new converts. It didn’t lead to December 25, like an Advent calendar with little chocolates inside, but to Epiphany (January 6). Advent comes from the Latin, adventus, meaning “arrival” or “coming,” and from the Greek, parousia, which is also translated as “presence,” especially, “presence after  absence” (or second coming). Back then, Advent was sometimes referred to as “the Lent of St. Martin’s” (and began on St. Martin’s day, November 11). Also, it was considered heretical to associate the Christian season too heavily with the winter solstice—too pagan. Sorry, but for me that’s exactly what’s evoked, and why I was drawn toward wanting to take part in the class. Well, light and an adventure.

absence” (or second coming). Back then, Advent was sometimes referred to as “the Lent of St. Martin’s” (and began on St. Martin’s day, November 11). Also, it was considered heretical to associate the Christian season too heavily with the winter solstice—too pagan. Sorry, but for me that’s exactly what’s evoked, and why I was drawn toward wanting to take part in the class. Well, light and an adventure.

I’ve made some surprising discoveries. In the book my co-leader assigned, Jill Duffield’s Advent in Plain Sight: A Devotion through Ten Objects, the first object is “gates.” I love that—I did a little digging and learned that the word “gate” appears 418 times in the King James Bible. In my introduction to the poems, I talked about how a gate can seem to be a barrier, but it’s really an invitation. A gate marks a path to be followed.

Poems, too, are gates. In my college teaching career I often encountered students who hated poetry. They saw a poem as a gate with a “no trespassing” sign hanging on it. But isn’t a poem, like a gate, an invitation? Open this. Walk through. See the world the way I see it. The first poem I brought was Naomi Shihab Nye’s “Kindness,” and the study group climbed onto the bus with me. “There’s communion here,” one participant gleefully noted. And another: “it’s a story of the good Samaritan!”

I found this short poem by Richard Bauckham on an Advent website, The Adventus Project. Details such as keeping vigil, a turn of the tide, and the cattle-shed roof lend it an Advent gloss, yet it’s multi-valent. A Druidic heart could be happy here. Bauckham is a theologian and poet who lives in Great Britain, but he could be my neighbor here in the Pacific Northwest in my house in the woods.

First Light

After all the false dawns,

who is this who unerringly paints

the first rays in their true colours?

We have kept vigil with owls

when the occult noises of the night

fell tauntingly silent

and a breeze got up

as if for morning.

This time the trees tremble.

Is it with a kind of reckless joy

at the gentle light

lapping their leaves

like the very first turn of a tide?

Timid creatures creep out of burrows

sensing kindness

and the old crow on the cattle-shed roof

folds his wings and dreams.

Richard Bauckham

https://richardbauckham.co.uk

My apologies for a somewhat wobbly, all-over-the place post. (Consider that I was told I wouldn’t be able to type for 6 weeks!)

Sunday evening at 11:00 my dog desperately needed a walk, so, despite the falling snow, we went out (with every caution for secure footing), and one reward was an owl hooting continuously from the snowy woods. No wonder my dog was restless. No wonder I love Bauckham’s poem: “We have kept vigil with owls.” Me, too.

It’s a gorgeous time of year, when you’re not all broken and needing a nap and a cookie (did you know that when you have a broken bone your body burns 20-30% more calories? Someone told me so—maybe just indulging my natural inclination).

When I first began gathering poems for the Advent class, I had a notion that the study participants would want to write with me. That didn’t happen (with the addition of a co-leader and the book, it became more conventional, which is fine), but it hasn’t kept me from writing. Early on, I came across a poem by Laura Walker titled “Psalm 100” (follow the link to read it for yourself). It made me open my Bible and reread Psalm 100. And then I wrote my own poem. Is it an Advent poem? Not really, unless you see it—like Bauckham’s poem—in a tradition of praise.

So, for solstice, here’s my poem in praise of light. From here on out, each day enjoy those extra few seconds of daylight.

Morning at Glen Cove

Make a joyful noise to the Lord, all the earth!

–Psalm 100, NIV

After a night of wind the cove sings.

Under cold water, a skein of herring,

above, a skein of glaucous-

winged gulls. Scraw of bald eagle

and great blue heron, sky

brimming, unfurled. In the early morning half-dark

sea lions bark, hoarse with so much praise.

Sunrise offers a kingfisher

chittering down the pink light.

Bethany Reid / 2022

listen).

listen).

But I promised myself I would do an end-of-the year round up of my submissions, and I’m not going to let my arm stop me.

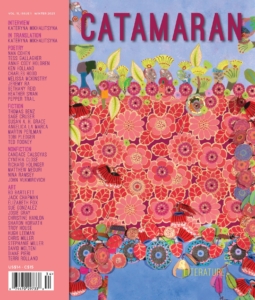

But I promised myself I would do an end-of-the year round up of my submissions, and I’m not going to let my arm stop me. Of course it’s way more fun to look at the acceptances. I’ve shared a few of these over the year, but recently the mail brought my contributor copy of

Of course it’s way more fun to look at the acceptances. I’ve shared a few of these over the year, but recently the mail brought my contributor copy of  appreciate all the on-line journals now encouraging writers, but it’s still a treat to get a copy of a real, flesh-and-bone journal.

appreciate all the on-line journals now encouraging writers, but it’s still a treat to get a copy of a real, flesh-and-bone journal.

cracked the head of my left radius bone, right up there in my elbow. I was in a fiberglass splint—looked like and felt like a big ol’ cast—for 7 days. The initial evaluation suggested the crack went all the way through. I couldn’t use my arm, I couldn’t get it wet, couldn’t practice my Christmas songs on the piano, couldn’t wear my Christmas sweaters. I couldn’t type! It took me four or five days just to figure out how to wear clothes and leave the house.

cracked the head of my left radius bone, right up there in my elbow. I was in a fiberglass splint—looked like and felt like a big ol’ cast—for 7 days. The initial evaluation suggested the crack went all the way through. I couldn’t use my arm, I couldn’t get it wet, couldn’t practice my Christmas songs on the piano, couldn’t wear my Christmas sweaters. I couldn’t type! It took me four or five days just to figure out how to wear clothes and leave the house. absence” (or second coming). Back then, Advent was sometimes referred to as “the Lent of St. Martin’s” (and began on St. Martin’s day, November 11). Also, it was considered heretical to associate the Christian season too heavily with the winter solstice—too pagan. Sorry, but for me that’s exactly what’s evoked, and why I was drawn toward wanting to take part in the class. Well, light and an adventure.

absence” (or second coming). Back then, Advent was sometimes referred to as “the Lent of St. Martin’s” (and began on St. Martin’s day, November 11). Also, it was considered heretical to associate the Christian season too heavily with the winter solstice—too pagan. Sorry, but for me that’s exactly what’s evoked, and why I was drawn toward wanting to take part in the class. Well, light and an adventure.

Ricardo Reis, and Álvaro de Campos. Pessoa created entire biographies for these alter-egos and considered them mentors and colleagues. He is, Zenith tells us, “an editor’s nightmare,” but also a treasure trove:

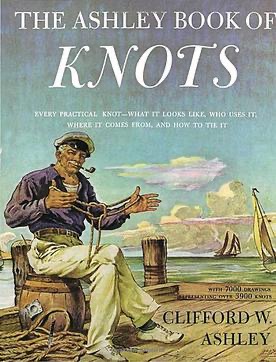

Ricardo Reis, and Álvaro de Campos. Pessoa created entire biographies for these alter-egos and considered them mentors and colleagues. He is, Zenith tells us, “an editor’s nightmare,” but also a treasure trove: I’ve been reading—or reading around in—another strange book, this one titled The Ashley Book of Knots. It was written and illustrated (3384 numbered illustrations) by Clifford W. Ashley, and first published in 1944. My copy belonged to my paternal grandfather (a Navy Seabee during WWII, which must explain why the book looks so well-read; I could go on a bit about my grandfather—as he was in his 40s and had 5 children when he enlisted; he kept his paychecks [from what I’m told], but wrote letters home signed, “Your poet, Gene”). His name and the date, Eugene H. King, 10/14/46, are written on the inside front cover. I can guess that the book came to belong to my father in 1959, when his father died. Since 2012, it has been mine, and this year I finally took it down from the shelf.

I’ve been reading—or reading around in—another strange book, this one titled The Ashley Book of Knots. It was written and illustrated (3384 numbered illustrations) by Clifford W. Ashley, and first published in 1944. My copy belonged to my paternal grandfather (a Navy Seabee during WWII, which must explain why the book looks so well-read; I could go on a bit about my grandfather—as he was in his 40s and had 5 children when he enlisted; he kept his paychecks [from what I’m told], but wrote letters home signed, “Your poet, Gene”). His name and the date, Eugene H. King, 10/14/46, are written on the inside front cover. I can guess that the book came to belong to my father in 1959, when his father died. Since 2012, it has been mine, and this year I finally took it down from the shelf. book, Dancing with the Muse in Old Age. After losing my father at age 82 to a stroke; after accompanying my mother through ten years of Alzheimer’s, stroke, and skilled-nursing care, then her death at age 86; I had pretty much decided that I’d better get things done right now, because I would be decrepit very very soon.

book, Dancing with the Muse in Old Age. After losing my father at age 82 to a stroke; after accompanying my mother through ten years of Alzheimer’s, stroke, and skilled-nursing care, then her death at age 86; I had pretty much decided that I’d better get things done right now, because I would be decrepit very very soon.