To Be of Use

My heartfelt thanks to all of you who listened to my radio interview and emailed or called. David Gilmour has to get at least half the credit, and Steve Nebel, sound engineer. I love it that you loved it.

And my apologies for being so absent this past month. I had good intentions — definitely meant to review a poetry book once a week in August — and instead let myself be swept up in a number of deadlines to be met (or slightly overshot…), one of which is still hovering.

Tuesday mornings for the past five years — or many Tuesday mornings, Fall, Spring, and Summer — I have been volunteering at my church, pulling weeds and pruning or whatever my “boss,” Fran, tells me to do. I’ve learned a lot about gardening from Fran, and though we didn’t often stand around talking, I got to know her through her work. Her plaid workshirt, her short gray cap of curls, her ready smile on seeing me. “Ah! You’re finally here!” Her incredible assortment of power tools.

Then, a couple weeks ago, Fran died.

In addition to being in charge of the church landscaping, Fran worked behind the scenes in almost every aspect of church life. I set aside the work for any excuse, and never put in more than my 90 minutes or 2 hours weekly (and felt virtuous about it), but for her the work was a calling, and a joy.

Marge Piercy

Ever since hearing the news of Fran’s death, I have been thinking of this poem, which someone gave me in my first year of teaching — it was on various office walls almost my entire career. I’m pleased to say that, after I sent the poem to him, my pastor read it at Fran’s memorial.

It’s my privilege this morning to share this poem with you. (See the poem at Poetry Foundation for the correct formatting.)

To Be of Use— by Marge PiercyThe people I love best

jump into work head first

without dallying in the shallows

and swim off with sure strokes almost out of sight.

They seem to become natives of that element,

the black sleek heads of seals

bouncing like half-submerged balls.

I love people who harness themselves, an ox to a heavy cart,

who pull like water buffalo, with massive patience,

who strain in the mud and muck to pull things forward,

who do what has to be done, again and again.

I want to be with people who submerge

in the task, who go into the fields to harvest

and work in a row and pass the bags along,

who are not parlor generals and field deserters

but move in a common rhythm

when the food must come in or the fire put out.

The work of the world is common as mud.

Botched, it smears the hands, crumbles to dust.

But the thing worth doing well done

has a shape that satisfies, clean and evident.

Greek amphoras for wine or oil,

Hopi vases that held corn, are put in museums

but you know they were made to be used.

The pitcher cries for water to carry,

and a person for work that is real.

From Circles in the Water (1982, Knopf)

else as part of her heart-filled service to the poetry community, edited the brilliant

else as part of her heart-filled service to the poetry community, edited the brilliant

I’m feeling stunned and honored and — even after a week has gone by — a bit disbelieving.

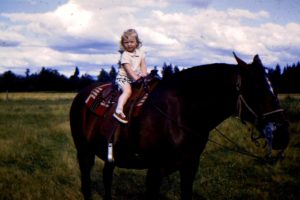

I’m feeling stunned and honored and — even after a week has gone by — a bit disbelieving. That is exactly what it felt like. It’s about more than my mother and father; it’s about growing up on a farm, and it’s about giving up that farm after my dad’s death in 2010. It’s about letting go of trees, fields, cows, fences, wells, ponds, bee boxes, books, orchard trees, creeks, barns… It’s about my mother’s memory loss, and how keenly that paralleled our folding away the family place, the farm my grandfather had owned before my father owned it. It’s about…so much.

That is exactly what it felt like. It’s about more than my mother and father; it’s about growing up on a farm, and it’s about giving up that farm after my dad’s death in 2010. It’s about letting go of trees, fields, cows, fences, wells, ponds, bee boxes, books, orchard trees, creeks, barns… It’s about my mother’s memory loss, and how keenly that paralleled our folding away the family place, the farm my grandfather had owned before my father owned it. It’s about…so much.