Louise Glück, 1943-2023

“Later I began to understand the dangers and limitations of hierarchical thinking, but in my childhood it seemed important to confer a prize,” she said. “One person would stand at the top of the mountain, visible from far away, the only thing of interest on the mountain.” —Louise Glück (from the New York Times, 10.13.23)

I know I am not alone in my shock on hearing that the poet Louise Glück (pronounced “Glick”) died this week, age 80, of cancer. The only American poet to win the Nobel prize (in 2020) since T. S. Eliot in 1948, Glück was also a recipient of the National Book Award and the Pulitzer Prize. She was the U.S. poet laureate from 2003-2004. Dipping into one article and obituary after another, I keep encountering superlatives: “one of America’s greatest living writers,” “sublime,” “among the most moving,” “among the century’s finest poets.”

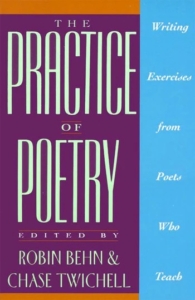

I own her Poems 1962-2012 (2012, Farrar, Straus and Giroux), and also The Wild Iris, which is included in Poems.  (While putting my own book into an order, I was looking at various “famous” books to see how they were arranged. It’s a gorgeous book, as the Pulitzer committee agreed.) Earlier this year I purchased a copy of Winter Recipes from the Collective (2021). It’s overwhelming to spend time with her poetry; you end up steeped in her mythologies, baffled by a personal story both tantalizingly near the surface and never quite within reach. (Consider a poem such as “The Dream,” a poem with two voices, beginning: “I had the weirdest dream. I dreamed we were married again,” and ending with the prosaic explanation, “Because it was a dream.”)

(While putting my own book into an order, I was looking at various “famous” books to see how they were arranged. It’s a gorgeous book, as the Pulitzer committee agreed.) Earlier this year I purchased a copy of Winter Recipes from the Collective (2021). It’s overwhelming to spend time with her poetry; you end up steeped in her mythologies, baffled by a personal story both tantalizingly near the surface and never quite within reach. (Consider a poem such as “The Dream,” a poem with two voices, beginning: “I had the weirdest dream. I dreamed we were married again,” and ending with the prosaic explanation, “Because it was a dream.”)

Pomegranate

First he gave me

his heart. It was

red fruit containing

many seeds, the skin

leathery, unlikely.

I preferred

to starve, bearing

out my training.

Then he said Behold

how the world looks, minding

your mother. I

peered under his arm:

What had she done

with color & odor?

Whereupon he said Now there

is a woman who loves

with a vengeance, adding

Consider she is in her element:

the trees turning to her, whole

villages going under

although in hell

the bushes are still

burning with pomegranates.

At which

he cut one open & began

to suck. When he looked up at last

it was to say My dear

you are your own

woman, finally, but examine

this grief your mother

parades over our heads

remembering

that she is one to whom

these depths were not offered.(from The House on Marshland, 1975)

Or consider this:

Penelope’s Stubbornness

A bird comes to the window. It’s a mistake

to think of them

as birds, they are so often

messengers. That is why, once they

plummet to the sill, they sit

so perfectly still, to mock

patience, lifting their heads to sing

poor lady, poor lady, their three-note

warning, later flying

like a dark cloud from the sill to the olive grove.

But who would send such a weightless being

to judge my life? My thoughts are deep

and my memory long; why would I envy such freedom

when I have humanity? Those

with the smallest hearts have

the greatest freedom.(from Meadowlands, 1996)

I’m trying to share enough so you see the range—this is a poet who published in The New Yorker for fifty years, after all—and the power present in even her early work. I’ve been noticing, as I flip through the pages, how often the color red occurs, as if Persephone’s pomegranate seeds keep replicating into other forms, and reminding us that, whatever is here, in our troubled and besieged turbulent world, it is our world.

The Night Migrations

This is the moment when you see again

the red berries of the mountain ash

and in the dark sky

the birds’ night migrations.It grieves me to think

the dead won’t see them—

these things we depend on,

they disappear.What will the soul do for solace then?

I tell myself maybe it won’t need

these pleasures anymore;

maybe just not being is simply enough,

hard as that is to remember.(from Averno, 2006)

This is praise from The New Yorker, after the 2020 Nobel:

The competing impulses to court and combat oblivion have driven Glück’s poetics from the beginning and continue to animate her recent work, including “Autumn,” from 2017: “Life, my sister said, / is like a torch passed now / from the body to the mind,” but “Our best hope is that it’s flickering.” Even the simplest language—as a juncture between body and mind, between what is shared and what is private, between definition and flux—serves as the site of this struggle, through which Glück has forged her inimitable, nearly supernatural craft. “It took what there was: / the available material. Spirit / wasn’t enough,” she writes, in “Nest.” Her poems offer a rare glimpse into the ineffable yet understand that it resides within—and is nothing without—the scaffolding of everyday stuff.

https://www.theparisreview.org/authors/26185/louise-gluck

A “rare glimpse into the effable,” indeed. Like me you are no doubt seeing tributes and poems all over the Web. This morning’s email brought a post from The Paris Review, sharing three poems by Louise Glück.

I cannot account for why, but I want to end with this stanza from the long poem, “An Endless Story,” in Winter Recipes from the Collective. A friend, on hearing about Glück’s passing, wailed, “We are losing our best poets!” I would like to remind her that we are not losing their poems. Glück, from what I read, did not particularly care for awards, or the “business” end of poetry. They got in the way of her art. How lucky we are that she persevered in sharing it.

I know what you think, he said; we all despise

stories that seem dry and interminable, but mine

will be a true love story,

if by love we mean the way we loved when we were young,

as though there were no time at all.—Louise Glück

else as part of her heart-filled service to the poetry community, edited the brilliant

else as part of her heart-filled service to the poetry community, edited the brilliant