Event Cancelled

Just a quick note to let you know my reading at Maplewood Presbyterian in Edmonds tomorrow (1.21.24) has been cancelled. Both my husband and I have the flu.

I’ll let you know when it is rescheduled.

Just a quick note to let you know my reading at Maplewood Presbyterian in Edmonds tomorrow (1.21.24) has been cancelled. Both my husband and I have the flu.

I’ll let you know when it is rescheduled.

Greetings & Gratitude would be a good subtitle for this post.

It’s been one of those years — I’m thinking of the news headlines, but also the loss of people dear to me. The last of my mother’s brothers died this summer, and a shocking number of my older cousins slipped away throughout 2023.

In the writing world, we lost several notables, including Linda Pastan and Louise Gluck. Locally, we lost the Edmonds poet John Wright. And, as I learned only last week, my poetry teacher, MFA advisor, and long-time mentor, Colleen McElroy died on December 12, 2023.

Perhaps that’s why I keep bumping into these lines from Wendell Berry:

To Know the Dark

To go in the dark with a light is to know the light.

To know the dark, go dark. Go without sight,

and find that the dark, too, blooms and sings,

and is traveled by dark feet and dark wings.

–Wendell Berry

In such times, when one doesn’t naturally dwell on gratitude, there is all the more reason to lean into it.

And, yes, I have had lots to be grateful for in 2023. Husband in good health. Daughters thriving, each in her own merry way. Spring brought a terrific road trip to see Yellowstone National Park (a first for me, westerner though I am), which included (in addition to lots and lots of driving) a stop in Spokane to see Bruce’s family. In August, my husband and daughters accompanied me to my family reunion in Doty, Washington, where I saw all my siblings, my mother’s two remaining sisters, plus many cousins, nieces, and nephews. With the aforementioned daughters I also went to Disneyland (for “Spooky Disney” in October, my girls’ choice for a trip to celebrate turning 30). On every trip I managed to reconnect with old friends, and a couple new ones, too.

And, there’s the writing thing.

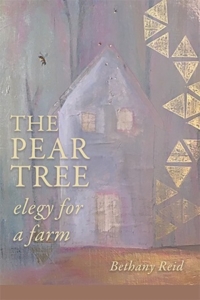

Besides numerous writing retreats and junkets with fun-loving poets, I am SO so grateful for my new book The Pear Tree: elegy for a farm, and to Lana Hechtman Ayers, the Albiso Award, and MoonPath Press.

I am grateful to have had a front-row seat to watch my friend Carla Shafer play her part in the 2023 Jack Straw cohort.

I took two classes in 2023, one being a repeat of the Summer Intensive (prose-writing) with Seattle writer and teacher Priscilla Long (I wrote a new story out of my ancestral-stories vein, and ginned out two new essays). The second class (which I audited) was taught at the University of Buffalo by Dickinson scholar Cristanne Miller on Emily Dickinson’s letters (a new edition of which, edited by Miller and Domnahl Mitchell, will be published by Harvard UP Spring 2024).

I kept up my practice of writing a poem every week this year, and I’m grateful for a whole bunch of 2023 publications. If you can bear with me, here’s the list:

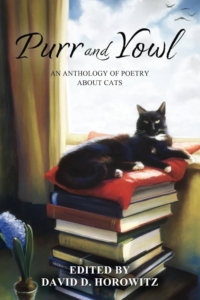

Two of my poems were included in Purr and Yowl, the delightful new anthology of poetry about cats, edited by Rose Alley Press’s David D. Horowitz, and published by World Enough Writers (https://worldenoughwriters.com).

Two of my poems were included in Purr and Yowl, the delightful new anthology of poetry about cats, edited by Rose Alley Press’s David D. Horowitz, and published by World Enough Writers (https://worldenoughwriters.com).

I have a poem in vol. 16 of Delmarva Review, which arrived in the mail only last week.

My poem, “Faith & Doubt,” was a semi-finalist for the Crab Creek Review Poetry Prize, and will appear in the forthcoming issue of Crab Creek Review.

The amazing Cirque: A Literary Journal for the North Pacific Rim published my poem, “In the Beginning.”

Some of these I’ve mentioned before, poems published earlier this year by the following (journals and on-line venues to put on your send-out list):

Descant; Naugatuck River Review: a Journal of Narrative Poetry that Sings; Braided Way; Escape Into Life; Hare’s Paw; Hole in the Head Review; The Dewdrop; Clackamas Literary Review; The Freshwater Review; Compass Rose Literary Journal; and Catamaran. (See my CV for clickable links to many of these.)

Oh, and I can’t forget my poem in the splendid anthology I Sing the Salmon Home, edited by Rena Priest and published by Empty Bowl.

Other than poems:

In 2023, my short story, “Wheels of the Bus,” was published at The Fictional Cafe, May 15, 2023. (It was a strange, experimental thing for me, not like any other story I’ve written, but there it is.)

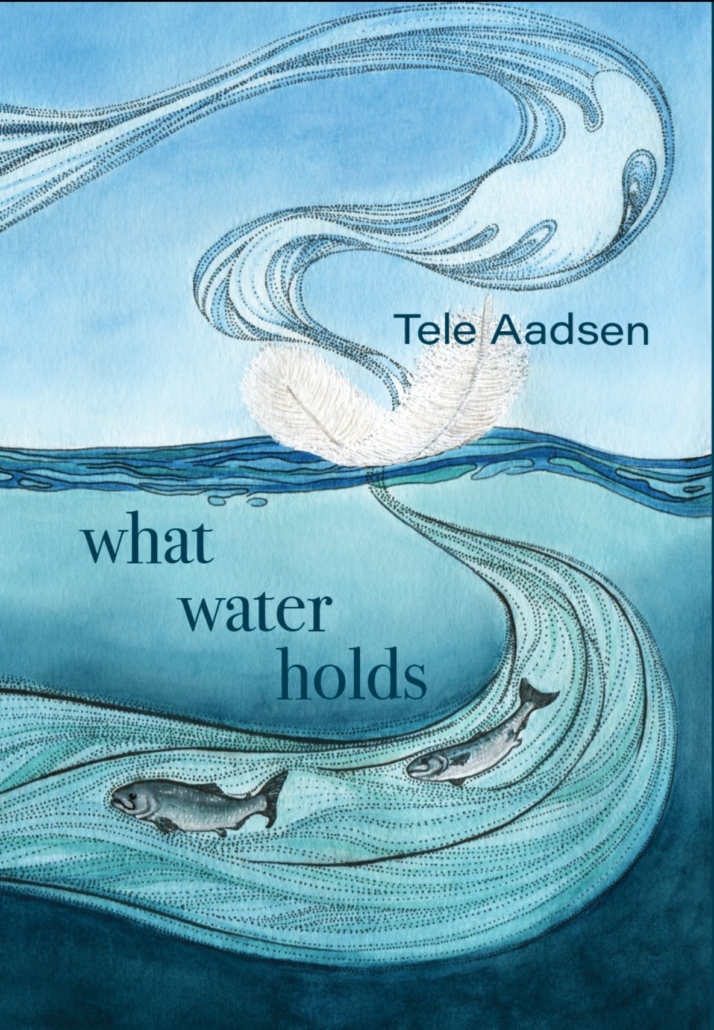

And, in addition to another April full of appreciative blog posts about poetry books, I had two reviews published in other venues: Tele Aadsen’s What Water Holds, at Raven Chronicles, and Sati Mookherjee’s Ways of Being at EIL (links are to my blog posts).

And…and…and…in addition to working with individual poets this year, I continued to facilitate a writing group (originally composed of EvCC outlaw writers), and taught a poetry class. I hope to do more of the same in 2024.

What else? In my old family newsletters, I always gave an update on our animals, so, briefly, our Tibetan Terrier,  Pabu, is now 15, sleeping a lot, but still with us. This year we lost our last “family” cat, Mr. Richie Stubbz, a beautiful huge tuxedo cat who had been living with our youngest daughter. (She has now adopted two kittens, Esteban and Simon.)

Pabu, is now 15, sleeping a lot, but still with us. This year we lost our last “family” cat, Mr. Richie Stubbz, a beautiful huge tuxedo cat who had been living with our youngest daughter. (She has now adopted two kittens, Esteban and Simon.)

Which prompts me to offer you a poem by my friend, poet Joannie Stangeland. The opening lines are what we’re all waiting for.

The Cat’s Poem

Waiting for snow to write the branches, grass, mud into a poem.

The day stays as gray as the cat who appeared last night.

The cat as gray as a ghost hunched on our front porch.

More fluff and purr than body, waiting to make our house his home.

A place left bare after our cat died.

The night was cold and colder.

Snugged close to the storm door — still, he stayed.

This gray cat with collar, tags, a name and numbers.

Maybe Lenny was lost or missing? The cat’s poem, I am here and I don’t know where.

My son texted the owners, who were out of town.

Could we take him to their house, let him in? and we did.

How strange the cat choosing our house and strange the staying.

This morning, I check the porch, hoping, knowing it’s wrong.

— Joannie Stangeland, Purr and Yowl (p. 186)

To all of you who have graced and lightened (and lit up!) my work and my days in 2023, thank you.

a view of Glen Cove during our November writers’ retreat

YOU CAN CALL IT BEAUTIFUL, Debra Elisa. MoonPath Press, PO Box 445, Tillamook, OR 97141, 2023, 107 pages, $17.99 paper, http://MoonPathPress.com.

I’m enthralled by this book of poems by Oregon poet Debra Elisa. My first impression was that her poems made a good contrast to mine, choreographed differently, her language distinct and pocked with color. But as I read more deeply, I began to see how our subjects and themes overlap: childhood songs, mothers and grandmothers, kitchens, birds, dogs, backyard gardens.

We also—if I can extend my interests beyond my new book—share a fascination with Emily Dickinson, as this cover blurb written by Allen Braden makes clear, calling Debra’s style “as idiosyncratic as Emily Dickinson’s with poems flaunting ‘breath and tiptoe glory and Clover.’”

And so much more, poems about social justice, poems about peace. Consider these lines:

You write often of Trees Dogs Birds

she says and I feel disappointed because I wishher to tell me You challenge us to consider justice

and love in all sorts of ways.(“Dear Friend”)

In short, this is an eclectic, surprising collection of poems.

What makes You Can Call It Beautiful a coherent collection (too) is the way Debra weaves her themes throughout, and unites all of it with her gift for sound and color. In “On the Way to Khajuraho” we encounter “Saris of aubergine azure black ayayas,” ending with “Ginger and Sunrise // charging again / this peregrine Land.” Having traveled so little myself, I’m both in awe of Debra, and grateful for her generous, joyful evocations.

Ekphrastic poetry—poetry about art—is another thread. This poem, quoted in full, evokes the cover art. At the same time it demonstrates the motif of elegy that twines all the way through the book:

Boy on Bicycle

after Graciela Rodo Boulanger’s

Le vainqueur (The Winner), etching, 1968One painting

on the living room wall

the boy pedals

grin and play

pastel blues

celadon

was gift to you

then left

to mewhen I asked

for this delight to hang

in my own home.The others—charcoal

and sketch a single brushstroke

acrylic eyes another crimson

your creations

beginnings and conversation

we continue.Your portrait—slight smile

glance to camera—

set on my desk

another on a kitchen shelf.You left us early

and some stories

you believed

were never

true.—Debra Elisa

Debra’s book is available from MoonPath Press, from https://bookshop.org, and from your local independent bookseller. You can read another poem by Debra at MoonPath on her author page, and you can read her blog, here: https://www.l-i-t.org/author/debelisa/

When I was given a copy of Tele Aadsen’s What Water Holds (Empty Bowl Press, 2023), I knew I wanted to review it. I’m so so grateful to Phoebe Bosché at Raven Chronicles for making room in their on-line forum for it. To read the review, click on this link: https://www.ravenchronicles.org/book-reviews/bethany-reid-what-water-holds.

You can learn more about the author at https://www.teleaadsen.com/.