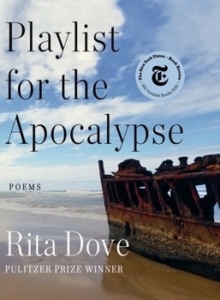

Rita Dove, PLAYLIST FOR THE APOCALYPSE

PLAYLIST FOR THE APOCALYPSE, Rita Dove. W.W. Norton & Company, Inc., 500 5th Avenue, New York, N.Y., 10110, 2021, 114 pages, $15.95, paper, www.wwnorton.com.

What a pleasure to read this book of poems by the inimitable Rita Dove, Pulitzer Prize winning poet, former U. S. Poet Laureate, editor (in 2011) of the Penguin Anthology of 20th Century American Poetry, etc., etc. I knew, before reading a single poem, that, 1) I would be confronted by challenging content; and 2) I was in capable hands.

I was not disappointed.

The poems are divided into six sections, each section addressing a facet of history, whether national, international, or  personal. “After Egypt” takes up the long history of emigration, displacement, and ghettoization. The section, “A Standing Witness,” emerged when she was tasked to collaborate on “a song cycle, bearing witness to the last fifty-odd years.” It begins with an epigraph:

personal. “After Egypt” takes up the long history of emigration, displacement, and ghettoization. The section, “A Standing Witness,” emerged when she was tasked to collaborate on “a song cycle, bearing witness to the last fifty-odd years.” It begins with an epigraph:

People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them.

—James Baldwin

All the better—Dove might be arguing here—that we face this history and do not flinch away from it. So, a poem about the girls murdered in the bombing of the 16th Street Baptist Church in Birmingham, Alabama (“Youth Sunday”); a poem titled for Trayvon Martin, “Trayvon, Redux”; a poem about Mohammed Ali (“our homegrown warrior, America’s / toffee-tone Titan; how dare he swagger / in the name of peace?”). A whole section of poems titled “The Angry Odes.”

As for the personal history, in the final section, “Little Book of Woe,” the poems tackle a difficult personal diagnosis. In “Borderline Mambo,” the lines are both dark and playful, with a powerfully effective anaphora in “as if” (and, later in the poem, riffs on that phrase): “As if you could get the last sip of champagne / out of the bottom of the fluted glass. / As if we weren’t all dying, as if we all weren’t / going to die some time, as if we knew for certain / when, or how.”

Opening that section, a long poem, “Soup,” which I’d love to include in its entirety:

When the doctor said I’ve got good news and bad news,

I thought of soup—how long it had been

since I had had the homemade kind,

the real deal where you soak the beans overnight…

A tour-de-force sentence that rolls on for 29 lines!

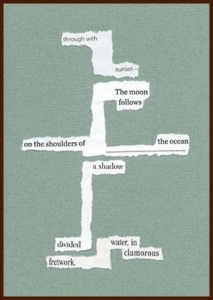

I could choose so many poems, and would love to send the whole book to you (the epigraphs!), but I’m led to show you that playful, word-drunk side, and so, this one, from the section titled, “The Angry Odes”:

Ode to My Right Knee

Oh, obstreperous one, ornery outside of ordinary

protocols; paramilitary probie parexcellence: Every evidence

you yield yells.No noise

too tough to tackle, tearsspringing such sudden salt

when walking wrenches:Haranguer, hag, hanger-on—how

much more maddeninginsidious imperfection?

Membranes matter-of-factlycorroding, crazed cartilage calmly chipping

away as another arduous ambulationbegins, bone bruising bone.

Leather Lothario, lone laboringgladiator grappling, groveling

for favor; fairweather forecaster, fickle friend,jive jiggy joint:

Kindly keep kicking.—Rita Dove

And if you didn’t notice the alliterative words in each line, go back now and read it again.

I first fell in love with Rita Dove’s Motherlove (1995). If you want to learn more about her, start with her pages (and numerous poems) at Poetry Foundation: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/poets/rita-dove.

At https://uva.theopenscholar.com/rita-dove you will find a list of Dove’s many accomplishments, including the 2024 Thomas Robinson Prize for Southern Literature.

not already subscribed to her near-daily blog

not already subscribed to her near-daily blog