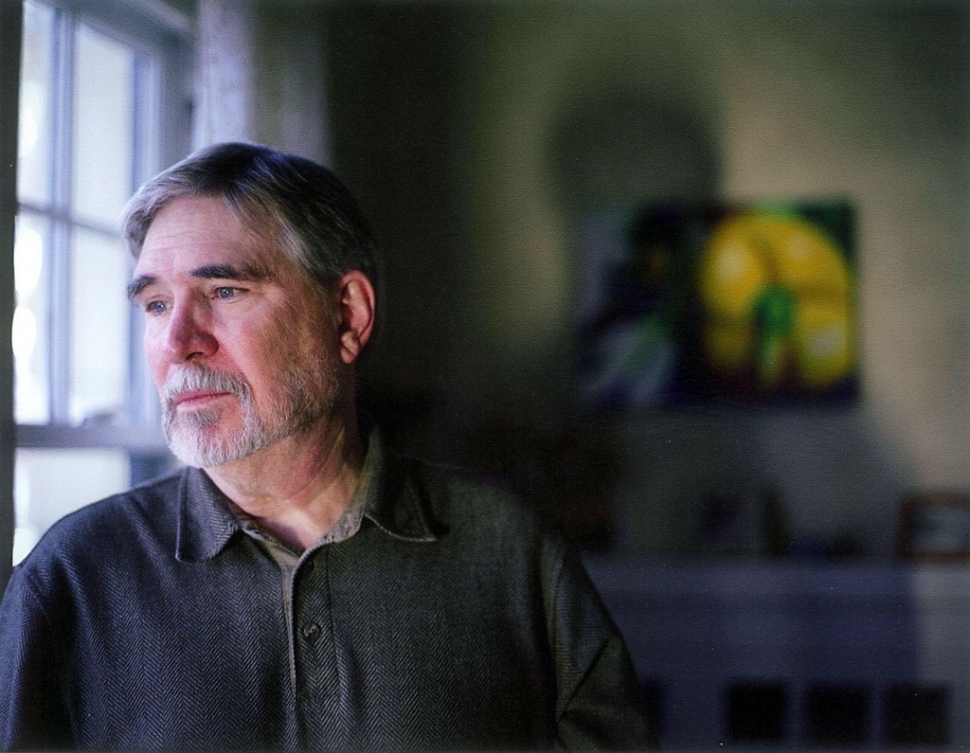

Christopher Howell’s Love’s Last Number

I had a lovely day. This morning I saw two old friends, women I met in Nelson Bentley’s poetry workshop 30+ years ago. I had the time wrong to pick up my daughter, by an hour, and so was able to take a walk on a nature trail I discovered between Lynnwood and Edmonds. This afternoon, my husband I went to see The Post, which was splendid, and had dinner out.

I had a lovely day. This morning I saw two old friends, women I met in Nelson Bentley’s poetry workshop 30+ years ago. I had the time wrong to pick up my daughter, by an hour, and so was able to take a walk on a nature trail I discovered between Lynnwood and Edmonds. This afternoon, my husband I went to see The Post, which was splendid, and had dinner out.

Plus: I spent spare moments all day reading this luminous book of poems: Love’s Last Number, by Christopher Howell (Milkweed, 2017).

Choosing which poem to share with you is not easy. One of the things I admire about Howell is that he is able to begin with one subject–the disappearance of the dog he had in childhood, for instance–but deftly shift to something you wouldn’t have guessed was related: “And what of the sea, another sort of road, Beowulf’s / whale road, St. Brendan’s miracle passage.” Except now, thanks to Howell, it’s obvious that they are related.

Many of the poems here reflect on the poet’s experiences in the Vietnam War. Throughout the book, time walks rough-shod over us, and also hauls us back, willy-nilly, into memories that shatter — or delight.

Here is the first poem in the book:

A Short Song

This is a song of our consciousness, that faltering

old man who will never make it across the bridge,

who sits down in the grit and dust of it with his wrinkled sack

of groceries that will have to last. A song of his foolish bravery

and terror, his hope that will not stay focused, that wanders

a springtime path between peach trees

and the berries, humming something, forgetting,

and humming again. A song of his wishes

tossing their hats in the wind and watching the last boat

depart, its cargo of nameless meaning casting flowers, waving

out of sight as the sun goes down.

It is a song of memory’s little ways and sudden corner-like loveliness

turned to smoke and broken glass it eats and eats

to stay marginally alive. A song of the bridge that never ends

really, and never whispers this

as the old man listens for the one spot of silence

or the one clear voice that might be his.