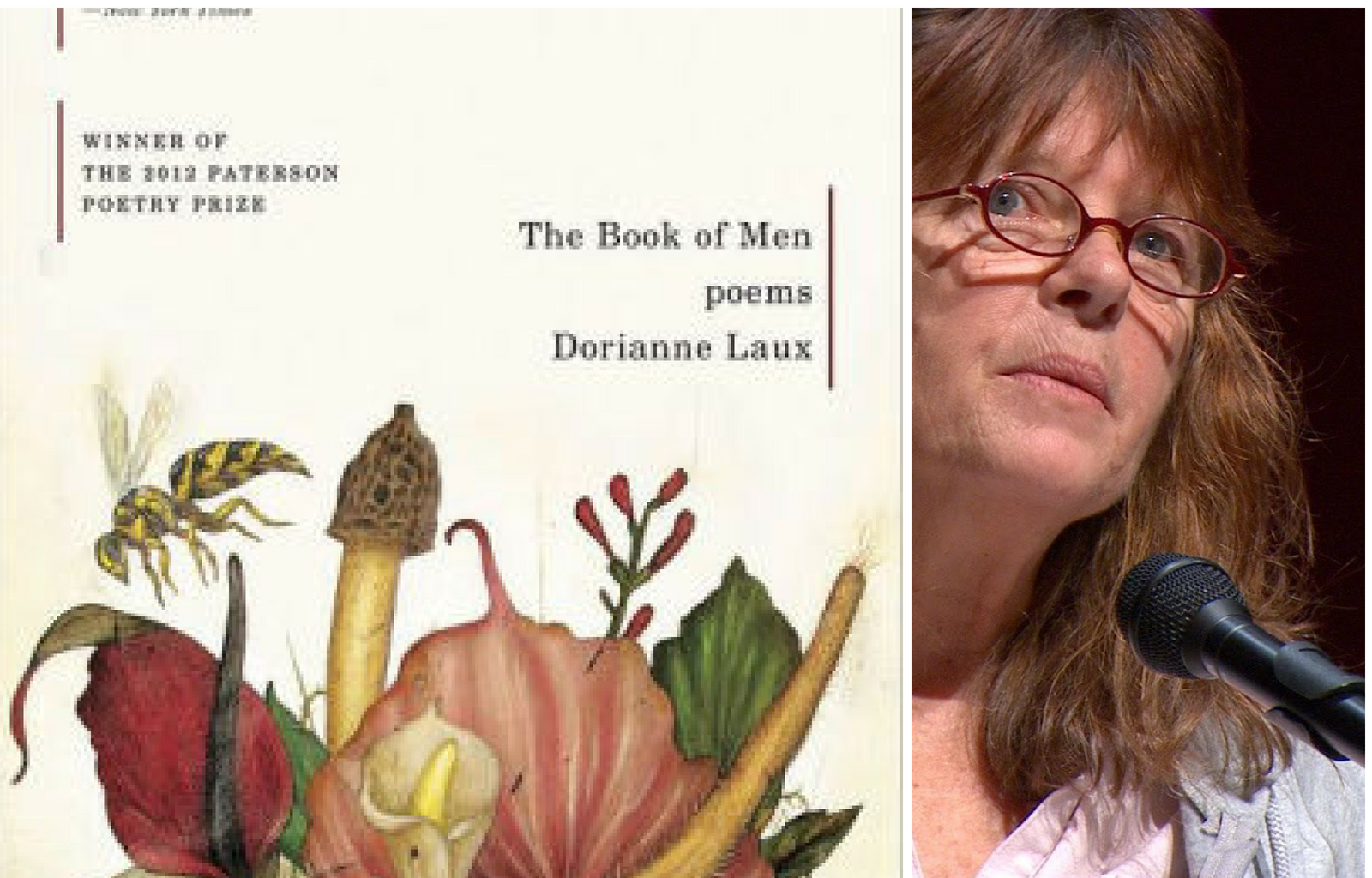

Dorianne Laux’s The Book of Men

How can I possibly write about Dorianne Laux without gushing?

How can I possibly write about Dorianne Laux without gushing?

This book qualifies for my series this month (poetry books I’ve been meaning to read cover-to-cover) because, in 2013, when she was the keynote speaker at Litfuse in Tieton, I came home with a whole stack of books, and I suspect this one got lost in the shuffle. I would like to swear that I did read The Book of Men (Norton, 2011) immediately and all the way through. But sitting here this evening, the poems seem awfully new to me. Whichever way it goes, I’m so glad I got to read them today, all in “one fell swoop,” as they say. I will be reading them again.

I love this poem — which appeared in the anthology A Cadence of Hooves (as did two of my poems) — a long time ago. And, yes, it, too, feels brand new, even though I know I’ve read it many times. I think what I’m confronting here is the freshness and vivacity of the images and words. As Ezra Pound famously said, “Poetry is news that stays news.”

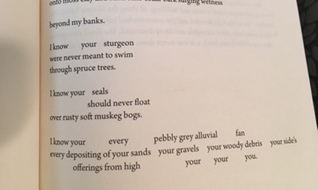

The Rising

The pregnant mare at rest in the field

the moment we drove by decided

to stand up, rolled her massive body

sideways over the pasture grass,

gathered her latticed spine, curved ribs

between the hanging pots of flesh,

haunches straining, kneebones bent

on the bent grass cleaved

astride the earth she pushed against

to lift the brindled breast, the architecture

of the neck, the anvil head, her burred mane

tossing flames as her forelegs unlatched in air

while her back legs, buried beneath her belly,

set each horny hoof in opposition

to the earth, a counterweight concentrated there,

and by a willful rump and switch of tail hauled up,

flank and fetlock, her beastly burden, seized

and rolled and wrenched and winched the wave

of her body, the grand totality of herself,

to stand upright in the depth of that field.

The heaviness of gravity upon her.

The strength of the mother.

In addition to the rough music of this poem, I hope you will notice that it is all one sentence until we reach the third to last line. Then the heaviness, gravity, and strength come under the poem in two short sentences that hold the weight of all of it together. A beautiful poem. An amazing poet.