In my journal each morning I write down my goals, big and small. I draw my circle and put my number-one focus inside it. Then the day unfolds–or (as it seems lately) unravels. What’s the nature of this message for me? What’s my assignment in the face of this?

Even on those mornings when I lose faith in my ability to handle any of it, Parker Palmer continues to inspire and nudge me along a path of compassion and understanding. For the people around me. And for myself.

In The Circle the sixth element is Coherence. One correspondent gave me a call, and told me all she was doing to work on congruence. Ah, I said.

Laura Day writes about finding ways to make your outer life look like your inner life–that’s congruence. And congruence is something Parker Palmer writes about in A Hidden Wholeness, too.

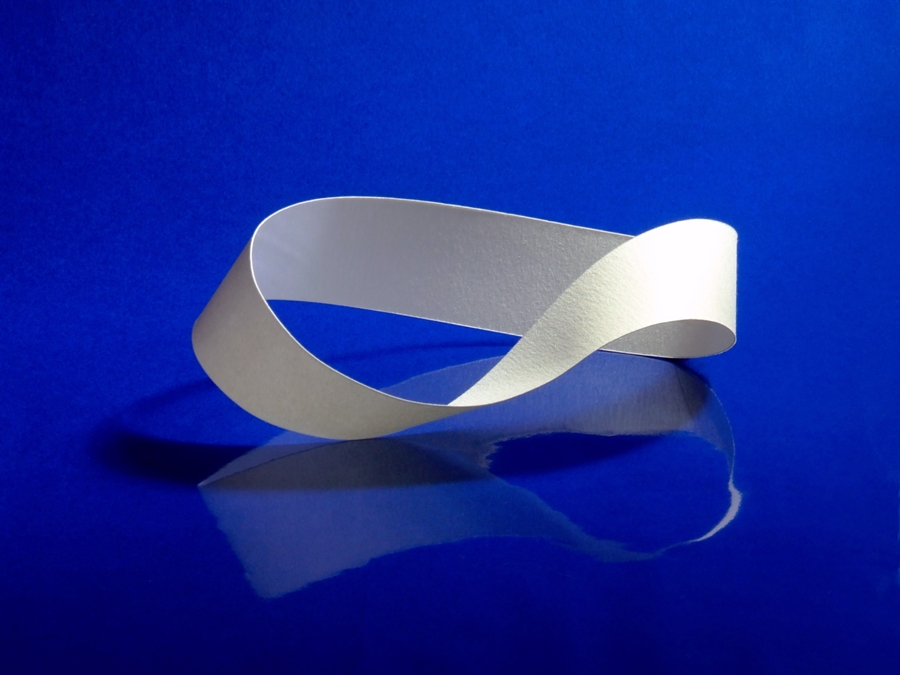

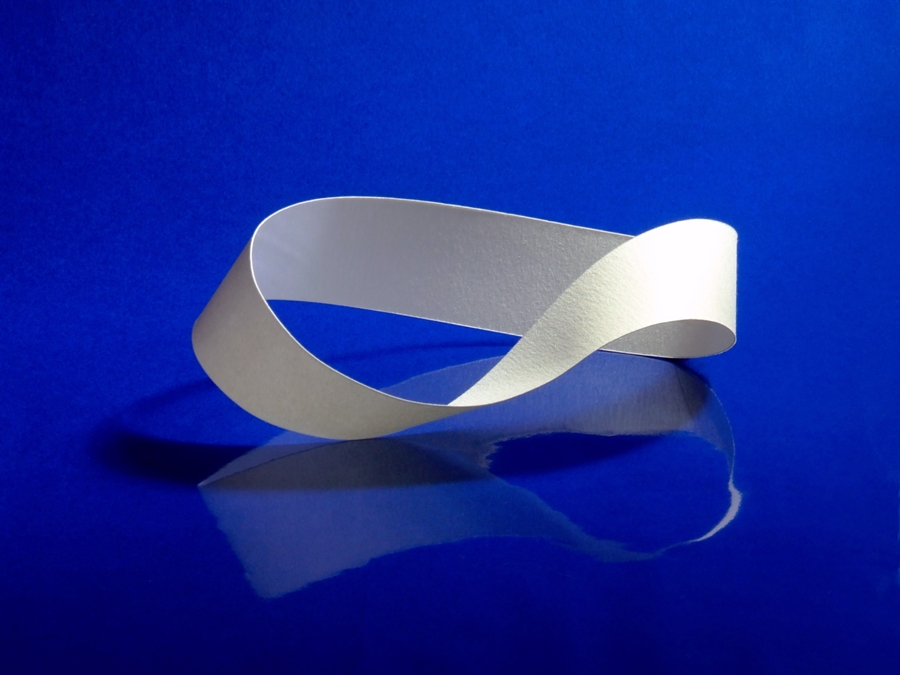

image from Wonderopolis.org

“We can survive, and even thrive, amid the complexities of adulthood by deepening our awareness of the endless inner-outer exchanges that shape us and our world and of the power we have to make choices about them. If we are to do so, we need spaces within us and between us that welcome the wisdom of the soul–which knows how to negotiate life on the Möbius strip [our inner and outer life at once] with agility and grace.” (A Hidden Wholeness 49)

Both Day and Palmer are encouraging their readers to make a journey of awareness and choice. When I falter, they encourage me to keep becoming aware, to keep making small, good choices.

“The deeper our faith, the more doubt we must endure; the deeper our hope, the more prone we are to despair; the deeper our love, the more pain its loss will bring: these are a few of the paradoxes we must hold as human beings.” Palmer, 83)

The gift of Coherence, Laura Day explains, is “Right Action.”

What do you need to do? If it’s huge and overwhelming, what one thing do you need to do next?

What needs to be healed, Parker Palmer asks, before you can go forward, before you can go deeper?

Now I become myself. It’s taken

Time, many years and places;

I have been dissolved and shaken,

Worn other people’s faces,

Run madly, as if Time were there,

Terribly old, crying a warning,

“Hurry, you will be dead before — ”

(What? Before you reach the morning?

Or the end of the poem is clear?

Or love safe in the walled city?)

(May Sarton, qtd. in Palmer, 90-91)

I have been sadly neglecting my blog, but working on other projects — one of which is a picture book for the family about my parents’ lives. Another of which has been reading poetry each morning (and writing

I have been sadly neglecting my blog, but working on other projects — one of which is a picture book for the family about my parents’ lives. Another of which has been reading poetry each morning (and writing

I had two big deadlines over the last week — and I slid in under the wire on each of them. I had a personal goal to submit my mystery novel to PNWA, deadline March 29, and who knows how good my entry was but I put everything into it, I took a deep breath, and I hit “send.”

I had two big deadlines over the last week — and I slid in under the wire on each of them. I had a personal goal to submit my mystery novel to PNWA, deadline March 29, and who knows how good my entry was but I put everything into it, I took a deep breath, and I hit “send.”