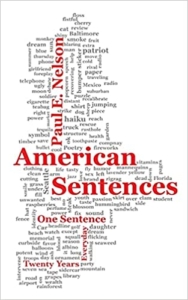

Paul E. Nelson, American Sentences

AMERICAN SENTENCES: ONE POEM, EVERY DAY, TWENTY YEARS, Paul E. Nelson. Apprentice House, Loyola  University Maryland, 4501 N. Charles St., Baltimore, MD 21210, 120 pages, $11.99 paper, www.ApprenticeHouse.com.

University Maryland, 4501 N. Charles St., Baltimore, MD 21210, 120 pages, $11.99 paper, www.ApprenticeHouse.com.

Honest-to-goodness, there’s nothing I can add that will make this better. (That is my 17 syllables today.) To learn more about the American Sentence, visit Paul’s homepage and navigate to: https://paulenelson.com/american-sentences-2/. All will be explained.

Paul E. Nelson is the founder of multiple poetry movements in the Pacific Northwest—or Cascadia, as he prefers. I very much recommend the August Poetry Postcard Fest. (Find lots of information here.)

Paul’s 17-syllable sentences in this book span twenty years (an earlier edition covers 14 years). They are sometimes silly, sometimes grounded in nature, sometimes sexy (sometimes raunchy), often elegiac, always curious. They offer a history of Paul’s personal life (loss of a father, loved mentors such as northwest legend Sam Hamill, birth of a child, travels). And they offer a history of our world in the decades they cover. Some of the sentences offer writing advice; some (many) would be good poem-starters.

Here’s a smattering:

1.06.09 – Michael says he gets writer’s block about 6 or 7 times a day.

N.20.10 – Want to call her and tell her I forgot my cell phone but I forgot my cell phone.

1.25.07 – David fantasizing: I wonder what she looks like without her cellphone.

10.2.13 – In the self-help section of Last Word Books, there are only typewriters.

10.29.14 – The biosphere’s being destroyed & you’re writing poems about pie.

12.18.14 – A two year old’s Jingle Bells: “No no no, no no no, no no no no…”

4.3.2015 – Sam tells me: “Reading Zukovsky is like doing a crossword puzzle.”

5.27.2015 – The buttercups in the neighbor’s lawn do not consider themselves weeds.

6.5.16 – If someone offers you a pancake shaped like the Buddha, eat it.

8.3.17 – Hacking at the moment’s shadow 17 syllables at a time.

1.14.19 – I know, drugs, surgery & radiation and edit your poems.

7.12.2019 – Amy Miller calls the postcard fest a “low-pressure laboratory.”

8.5.19 – If you have no inner life by age 60, your life caves in on you.

12.15.20 – Your yoga pants collection is not indicative of an inner life.

Paul has a new book, or an old book in a new edition: And when I attended his #nationalpoetrymonth book launch a couple weeks ago, I bought American Sentences and told him I would read it. So, this morning, I did.

Paul has a new book, or an old book in a new edition: And when I attended his #nationalpoetrymonth book launch a couple weeks ago, I bought American Sentences and told him I would read it. So, this morning, I did.

Open the PDF at his American Sentences page, scroll to the bottom, and at the end you’ll find this:

Exercise: Go out and take 10 minutes to slow down, look around and get two American Sentences. It is not as easy as writing seventeen syllables, but having a notebook on you at all times, making a commitment to writing one a day, or two a week, or whatever, will keep your hand in it at times when you are not writing much else. You can also go back and have a short, imagistic journal that may serve as source material for other poems. Remember: Imagistic, Juxtaposition, Found Poems, Mindfulness, rhythm, busted syntax, condensed, demotic speech. Refrain from commentary. It’s a bad habit. American Sentences, on the other hand… Look! He says he has American Sentences on the other hand!

Slow down, look around, carry a notebook. How can this be anything but good?

opening paragraph of the NYer article, I thought of William Carlos Williams: “It is hard to get the news from poems / but men die miserably every day / for lack of what is found there.”

opening paragraph of the NYer article, I thought of William Carlos Williams: “It is hard to get the news from poems / but men die miserably every day / for lack of what is found there.”

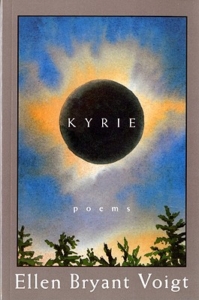

couldn’t differ more from Seuss’s Frank. Well, maybe there’s a correlation in that both collections tell a dark story. Voigt is telling, however, not a personal story, but one set during the flu pandemic of 1918-1919.

couldn’t differ more from Seuss’s Frank. Well, maybe there’s a correlation in that both collections tell a dark story. Voigt is telling, however, not a personal story, but one set during the flu pandemic of 1918-1919.

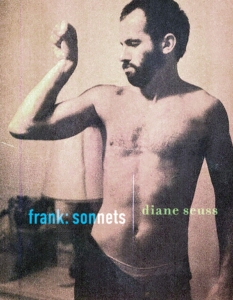

narrative test the boundaries of the conventional form” (Terrance Hayes). “…an ambitious, searing, and capacious life story. The poems themselves use an ecstatic syntax to unite Seuss’s lyric leaps from one wretched sweetness to another….narratives of poverty, death, parenthood, addiction, AIDS, and the ‘dangerous business’ of literature are irreducible” (Traci Brimhall). In short, it was a little like reading a memoir—bizarre, fragmented, mesmerizing. When I first purchased this book and read a poem here and there, I was missing the point.

narrative test the boundaries of the conventional form” (Terrance Hayes). “…an ambitious, searing, and capacious life story. The poems themselves use an ecstatic syntax to unite Seuss’s lyric leaps from one wretched sweetness to another….narratives of poverty, death, parenthood, addiction, AIDS, and the ‘dangerous business’ of literature are irreducible” (Traci Brimhall). In short, it was a little like reading a memoir—bizarre, fragmented, mesmerizing. When I first purchased this book and read a poem here and there, I was missing the point.