Caitlin Scarano, The Necessity of Wildfire

THE NECESSITY OF WILDFIRE, Caitlin Scarano. Blair, Durham, North Carolina, 2022, 78 pages, $16.95 paper, www.blairpub.com.

I have to tell you that I fell hard for this book. I was cobbling together my Escape Into Life review of Ada Limón’s The Hurting Kind, and came across an announcement about the Elliott Bay book launch of The Necessity of Wildfire,  2022 winner of the Wren Poetry Prize, selected by Limón. The recording of the event, featuring both poets, is available here, and at Scarano’s website.

2022 winner of the Wren Poetry Prize, selected by Limón. The recording of the event, featuring both poets, is available here, and at Scarano’s website.

The book has now won a 2023 Pacific Northwest Book Award, well deserved. As Limón describes it:

“Hungry, clear-eyed, tough, and generous…. Cinematic and sound-driven, these are brilliant and honest personal poems that open up to the larger universal truths.”

So, let me try to tell you about my experience, reading The Necessity of Wildfire. Scarano’s second book, it braids together multiple themes: childhood dangers, adult love and trauma, domestic violence, illness, animals (both scary and beloved), and landscape, landscape, landscape. Cacophony, euphony, lines that want to be spoken aloud: “Who made my wrists / of wire. Copper conductors of heat / and electricity. Think of the synaptic / dance, jaw loose daze…” (“A Poem to Multiple Men”).

At times the voice is matter-of-fact, telling a story, but the themes get twisted together like a braid, or like a wire with razor sharp edges. Consider as an example, the opening lines of this poem:

I am driving by a field. Mountains crusted with a gold decay

surround me. My mother called yesterday; they finally have

a diagnosis. In the field I notice a cow on her side,

a trembling mass. Sick paternal aunts and cousins

I’ve never met. I get out of the car and move toward the wire

fence. Inherited autosomal recessive mutation.(from “Calf”)

Scarano grew up in Southside Virginia (which I had to look up) and now lives near Bellingham, Washington. Along the way, she’s studied in Alaska, and Antarctica. She has a scientist’s eye, and a humanitarian’s mission: “To not harm / each other is not enough” she writes in “The houses where they eat the lambs,” continuing with these provocative lines:

I want to love you

so much you have no before. No mother,no bower, no history of burning doors.

The sea with her rising wet ash. To be marrow

intimate. A crime committed…

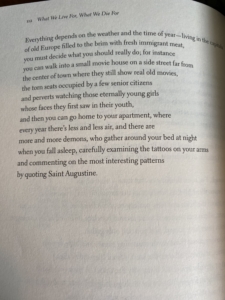

I can see that I will be excerpting the entire book if I keep on. Here’s a poem that I keep rereading, noticing the enjambments, those tricky ends / beginnings of lines that shift the meaning of the words:

Oxbow

What good is a long life? The river smells

of where it comes fromnot where it is going. I’ve never lived

by water until this. I grew up between dairyfields and oak-pine forests. Sisters

hiding behind a crushedvelvet window curtain. Girl,

static, ghost. There was a clockhigh on the wall in the living

room. One night, I swear, the soundgrew so loud. My blood’s ticked ever

since. Travel far from where they raised youand your blood will still burn.

In a dream, the lower half of my bodyis buried in snow. The rest scatters

for sky. Along the river, a conspiracyof crows take up in a white pine. A bevy

of swans follow. The contrast is too muchfor the field to contain. Someone asked me

my greatest subject. Shame, I saidwithout thinking. My lover keeps a folding

knife in the bottom drawer of his dresser.I like to take it

out when he isn’t here. Dig littlenotches into the back of our headboard

with the tip. One for every secretwe or the water withhold.

—Caitlin Scarano

The book, itself, is lovely. I found a copy at my local library, then saw it at Edmonds Bookshop and had to own it. I keep telling people I’ll lend it to them, but I can’t seem to let it go.

up the Great Leap Forward and learned that it was a 5-year campaign (1958-1962) to transform China from an agrarian economy into a communist society, which resulted in a famine costing 36 million lives (this, from the long poem “When You Died”; see Wikipedia on “The Great Leap Forward” at

up the Great Leap Forward and learned that it was a 5-year campaign (1958-1962) to transform China from an agrarian economy into a communist society, which resulted in a famine costing 36 million lives (this, from the long poem “When You Died”; see Wikipedia on “The Great Leap Forward” at