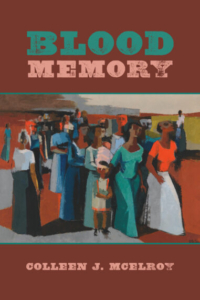

BLOOD MEMORY, Colleen J. McElroy. University of Pittsburgh Press, Pittsburgh, Pa., 15260, 2016, 112 pages, $15.95 paper, www.upress.pitt.edu.

I met Professor Colleen J. McElroy when I was a newly minted MFA student at the University of Washington in 1985. If I had to characterize her in one word, it would be “storyteller.” Yes, she taught us (a lot) about poetry and the making of poems, but part of the glamor of her classes, for me, was when she would lean back in her chair, half-close her eyes, and begin telling a story. She put all of us in a trance.

If I had to characterize her in one word, it would be “storyteller.” Yes, she taught us (a lot) about poetry and the making of poems, but part of the glamor of her classes, for me, was when she would lean back in her chair, half-close her eyes, and begin telling a story. She put all of us in a trance.

The stories were about her travels—which were many; about poets she’d met and read with all over the world; about her St. Louis childhood; about her family, particularly the women who taught her how to tell stories. Reading Blood Memory transports me back to her classrooms, and to her office where, as my faculty advisor, she met with me (and regaled me) weekly. I read these poems, and I hear her voice, its cadence, its rich timbre, her laughter. And, sometimes, I can see her, fixing me with a look that she must have learned at the feet of the indomitable women who peopled her childhood.

from “Paint Me Visible”:

in a family of beautiful intelligent and profoundly

crazy women one danced in the dark

to soothe her nerves another wove shawls

from her husband’s hair and discarded both

when the work was done another read palms

tea leaves cards anything that left an imprint

on her inner eye neighbors said she saw

things nobody else could describe

From hopscotch rhymes to blues, through birth, abortion, estrangement, exile, and return no one can describe this world the way McElroy can. Here is the book’s opening poem:

The Family Album

call it blood memory for I am the only

one left to identify by name the ancestors

I am the only one left of the women

who sat around grandmother’s oak table

and wove the stories of who and where

who knows the half of it and when

I am the answer to the questions

my mother’s sisters swallowed:

What will you do with that child?

I know now that I am here to give

voice to tongues never silent

and doors closing too quickly

I am of the age where death comes

easily and visits often in those little

obit notes of passing reminding us

how we’ve neglected dear ones

now lived again through fading pictures

stuck to crumbling pages

I buy tickets to places I may never visit

spend hours trying to remember

if the image stuck in my head has origins

in a dream or some foggy night

slipping past almost unnoticed

I am the last female of a family

of women who wove the fabric

of stories into doilies and slip covers

I am the child with sparrow legs

sock heels stuck halfway in her shoes

drinking the last of the metaphors left

in teacups on the table unattended

—Colleen J. McElroy

From the back cover, these words of description and praise:

“She is the last woman of her line. Her new poems end and begin with A. Phillip Randolph and Pullman Porters, her enjambments are Ma Rainey and Lawdy Miz Cloudy, her leading men are the last Black men on the planet named Isom, her major planets are porches and backroads. She is still the master storyteller to the 60 million of the Passage. When I didn’t know how to be a poet, I first read Colleen McElroy to slowly walk the path to how.” —Nikki Finney

Exactly so.

To read more about Colleen J. McElroy, find her at The Poetry Foundation, Historylink.org, and I recommend this interview with Bill Kenower of author magazine.org. Here she talks about where she learned to tell stories. And (love this) she talks about poetry as not just any relationship, “but an affair.” Maybe that helps explain the clotted love that breaks to the surface in poem after poem in this book.

I first read Blood Memory when it was released in 2016. It was a delight to read it this morning and enter the trance again.

https://artsci.washington.edu/news/2022-05/colleen-mcelroy-honored-through-room-dedication

And, again, the link to her at historylink.org.

still writing, living somewhat local to me, in Bellingham, Washington. I read a few of her poems on-line, stumbled onto Paraclete (also the publisher of Christine Valters Paintner), liked the cover of Eye of the Beholder, and purchased it.

still writing, living somewhat local to me, in Bellingham, Washington. I read a few of her poems on-line, stumbled onto Paraclete (also the publisher of Christine Valters Paintner), liked the cover of Eye of the Beholder, and purchased it.

If I had to characterize her in one word, it would be “storyteller.” Yes, she taught us (a lot) about poetry and the making of poems, but part of the glamor of her classes, for me, was when she would lean back in her chair, half-close her eyes, and begin telling a story. She put all of us in a trance.

If I had to characterize her in one word, it would be “storyteller.” Yes, she taught us (a lot) about poetry and the making of poems, but part of the glamor of her classes, for me, was when she would lean back in her chair, half-close her eyes, and begin telling a story. She put all of us in a trance.