W. S. Merwin, 1927-2019

GARDEN TIME, W. S. Merwin. Copper Canyon Press, Post Office Box 271, Port Townsend, Washington, 98368, 2016, 78 pages, $16 paper, www.coppercanyongpress.org.

When I was in the MFA program at the University of Washington, I helped to bring W. S. Merwin to read as part of our Watermark Series, and I was one of a handful of students to be granted a one-on-one tutorial with him. Born the same year as my father, he wore a logger’s hickory stripe shirt that day, and he had intense blue eyes, like my logger father. I could hardly speak, I was so in awe of him.

our Watermark Series, and I was one of a handful of students to be granted a one-on-one tutorial with him. Born the same year as my father, he wore a logger’s hickory stripe shirt that day, and he had intense blue eyes, like my logger father. I could hardly speak, I was so in awe of him.

I stumbled across this book recently while browsing a small bookstore, and, surprised I hadn’t seen it when it was first published, I grabbed it up. Garden Time, which is time outside of our usual everyday time, is a perfect title. Merwin wrote it—dictating the poems to his wife, Paula—when he was losing his eyesight. Among the 62 short, contemplative poems I could pick out any number of “favorites.” It’s hard not to choose “Pianist in the Dark,” which opens with these lines: “The music is not in the keys / it has never been seen / the notes set out to find / each other / listening for their way.” And these notes:

Rain at Daybreak

One at a time the drops find their own leaves

then others follow as the story spreads

they arrive unseen among the waking doves

who answer from the sleep of the valley

there is no other voice or other time—W. S. Merwin

An Irish Times reviewer described the poems as “graceful, often stunning,” and, “Focused brilliantly on what we see and how we are seen.” I couldn’t agree more.

Not Early or Late

Is it I who have come to this age

or is it the age that has come to me

which one has brought along all these

silent images on their shadowy river

appearing and going away as the river does

all without a word though they all know me

I can see that they always knew where to find me

bringing me what they know I will recognize

what they know only I will recognize

to show me what I could not have seen before

then leave me to make sense of my own questions

going away making no promises—W. S. Merwin

Merwin was elected U. S. Poet Laureate in 2010, and was the recipient of two Pulitzers for Poetry as well as many other awards over his long life of writing. Here’s the book page at Copper Canyon, and you can learn much more about his spiritual practices, and gardening practices in this profile at Poetry Foundation.

memoir, You Could Make this Place Beautiful; and, when another friend—hearing that I was writing a blogpost—said, “Maggie Smith, the memoirist?”

memoir, You Could Make this Place Beautiful; and, when another friend—hearing that I was writing a blogpost—said, “Maggie Smith, the memoirist?”

Mark Strand, and decided it was time. And then the book sat on my shelf. Until this morning. Well, until Sunday, when I began it, and Monday, when I utterly failed to “get” it, until this morning when I decided to sit quietly and ask nothing of myself except to reread the book all the way through.

Mark Strand, and decided it was time. And then the book sat on my shelf. Until this morning. Well, until Sunday, when I began it, and Monday, when I utterly failed to “get” it, until this morning when I decided to sit quietly and ask nothing of myself except to reread the book all the way through.

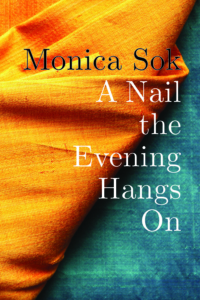

The poems in A Nail the Evening Hangs On are not those poems.

The poems in A Nail the Evening Hangs On are not those poems.