The Lexicon

Lexicon: “the vocabulary of a person, language, or branch of knowledge”

A lexicon can be vast, but it can also be narrow and exact. Horse people have a lexicon. Dock-workers have a lexicon. Waitresses have a lexicon.

My first assignment in the poetry class I’m teaching is to list 25 words relating to a subject. I have heard this assignment called “a word bucket.” It is meant to be both non-threatening (an easy threshold to trip over, into the class), but also inspiring. I shared examples of lexicons I’ve written:

- for parts of a horse bridle

for the names of every part of a piano

for the names of every part of a piano- for the skilled-nursing home where my mother spent her last years

- for northwest flora and fauna

- for my farm childhood

We all have lists of this sort in our heads, but deliberately listing the words, I’ve found, results in more exactness, and — very often — surprising directions one might follow.

Recently I wrote a poem about the word “bless.” I had high hopes for the poem, and started by looking up the definition and etymology of bless:

bless (v)

Middle English blessen, from Old English bletsian, bledsian, Northumbrian bloedsian “to consecrate by a religious rite, make holy, give thanks,” from Proto-Germanic *blodison “hallow with blood, mark with blood,” from *blotham “blood” (see blood (n.)). Originally a blood sprinkling on pagan altars.

This word was chosen in Old English bibles to translate Latin benedicere and Greek eulogein, both of which have a ground sense of “to speak well of, to praise,” but were used in Scripture to translate Hebrew brk “to bend (the knee), worship, praise, invoke blessings.” L.R. Palmer (“The Latin Language”) writes, “There is nothing surprising in the semantic development of a word denoting originally a special ritual act into the more generalized meanings to ‘sacrifice,’ ‘worship,’ ‘bless,’ ” and he compares Latin immolare (see immolate).

The meaning shifted in late Old English toward “pronounce or make happy, prosperous, or fortunate” by resemblance to unrelated bliss. The meaning “invoke or pronounce God’s blessing upon” is from early 14c. No cognates in other languages. Related: Blessed; blessing.

( lifted straight from https://www.etymonline.com/word/bless )

I also looked up how many times “bless” appears in the King James Bible (lots, in various forms of the word, but I’ll let you check for yourself.)

Google makes it almost too easy to do this assignment. I picked out only certain words from etymonline, but as I wrote them into my notebook, I kept coming up with more. I scribbled it all down: religion, blessing, ritual, sacrifice, blood, holy, bend, knee, praise, thanks, bliss, hallow, bledsian, bloedsian (which made me think of druids, so), druids, pagan, church, bees (not sure where that came from, but I began to know at that point where the poem would be located, or the two places it would be located), pear tree, limbs, pears, blossoms, path, foyer (of my childhood church), yellow, “blood of the lamb,” washed in…, grandmother, stones, honey, bodies.

Google makes it almost too easy to do this assignment. I picked out only certain words from etymonline, but as I wrote them into my notebook, I kept coming up with more. I scribbled it all down: religion, blessing, ritual, sacrifice, blood, holy, bend, knee, praise, thanks, bliss, hallow, bledsian, bloedsian (which made me think of druids, so), druids, pagan, church, bees (not sure where that came from, but I began to know at that point where the poem would be located, or the two places it would be located), pear tree, limbs, pears, blossoms, path, foyer (of my childhood church), yellow, “blood of the lamb,” washed in…, grandmother, stones, honey, bodies.

My list was longer, but many of these found their way into a rough draft of a poem about a pear tree. (I hadn’t expected the bees, or the pear tree.)

You can see that the assignment could be narrowly focused, but doesn’t have to be — you can free associate. What 25 words (or 100 words) do you associate with your mother, with the house you now live in, with your kitchen, with your cubicle at work?

It can be interesting, by the way, to do this assignment with someone else’s poem, particularly one that wows you. Start by listing every noun, maybe add the verbs. Are the words related? (Probably, but — again — perhaps in ways you didn’t imagine until you looked at them scrambled together on the page.)

Easy peasy.

I even try?

I even try?

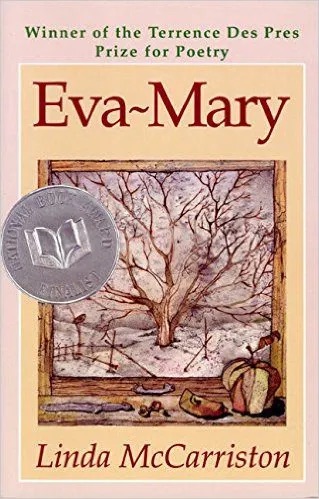

eventually did. Since then—for most of the last thirty years—it has been shelved above my writing chair with a lot of other poetry books.

eventually did. Since then—for most of the last thirty years—it has been shelved above my writing chair with a lot of other poetry books.