Joseph Powell: THE SLOW SUBTRACTION: A.L.S.

THE SLOW SUBTRACTION: A.L.S., Joseph Powell. MoonPath Press, P.O. Box 445, Tillamook, OR 27142, 2019, 80  pages, $16, paper, http://MoonPathPress.com.

pages, $16, paper, http://MoonPathPress.com.

The Slow Subtraction is a collection of love poems. Difficult content, yes, addressing the diminishment visited upon a beloved with a chronic illness, but love poems, no less.

We never think of coughing

as a blessing

until we can’t cough. (“Ironies”)

Practical realities, the minutiae of care-giving, but also the gift of close attention: “A studious winter light magnifies the afternoon” (“Yakima Canyon in Winter”). Or consider these lines:

the carnelian arrowhead found in the garden,

the painted floral plate she bought in Greece,

the cinnabar snuffbottle (“Ringing”)

According to his biographical note, Joseph Powell now lives on a small farm outside Ellensburg, gardening, fly-fishing, and scrounging, “hunting mushrooms and agates, picking berries,” after thirty years teaching in the English department at Central Washington University. Lucky students, to have had the grace of such attention to the trajectory of details, beauty and danger, in every life.

I wanted to give you “At Adrianne’s House on Patmos” (“The lemon trees curl inward / and the warmth is a soft net over us”), but I think it has to be this one:

Faith

She has passed through the heavy doors of grace.

Its spareness a kind of amplitude.

Small things wash away like bathwater.

Even the choking for air after a bad swallow

has lost its wild-eyed reflex

as if she’s stroking the leopard beside her

until breath comes back.Her faith is in the rightness of demise,

in the mind’s transformative evolution,

the feel of the enlarged pulse

in the sway of events, the way pettiness

is candleflicker against the passing night,

the divinity of sleep on cool afternoons.She has taken the sacrament of faith

like a host into her failing body.

It enlightens the spiral of fragments

in memory’s house—dust in small sunlit rooms.

Love is the old dog asleep at the door.—Joseph Powell, The Slow Substractions: A.L.S.

I read (or reread) this book while sitting in the ER beside my husband’s bed (he is fine now). I was going to begin this post with something like “I don’t recommend…,” but it was actually the perfect setting.

Life is always going on all around us. The ten thousand things. When we are caught up in the drama of it, stopping to notice those details is a great help.

Joseph Powell has published 6 books of poetry. You can read more about him, and his poem “The Snake,” also from this book, at https://moonpathpress.com/JosephPowell.htm. See his poem (and hear him read) “Upside Down and Flying” at https://www.terrain.org/2019/poetry/joseph-powell/.

chickens, China.

chickens, China.

for her. Winter, the sixth volume in the Hobblebush Granite State Poetry Series, was the first to arrive, and is now on sale for $9 at Hobblebush Books (use this link:

for her. Winter, the sixth volume in the Hobblebush Granite State Poetry Series, was the first to arrive, and is now on sale for $9 at Hobblebush Books (use this link:

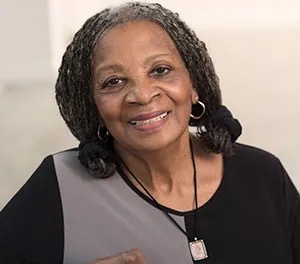

McElroy, who died in December. I have almost all 16 of her books, most of them signed by her. I considered her a friend, as well, and am ashamed that I hadn’t seen her since before 2020.

McElroy, who died in December. I have almost all 16 of her books, most of them signed by her. I considered her a friend, as well, and am ashamed that I hadn’t seen her since before 2020.