Ted Kooser’s WINTER MORNING WALKS

WINTER MORNING WALKS: ONE HUNDRED POEMS TO JIM HARRISON, Ted Kooser. Carnegie-Mellon University Press, Pittsburgh, 2000, 120 pages, $15.95, https://www.cmu.edu/universitypress/.

I am here to confess that I have been making everything hard. What brings on such a mood—a straitjacket twisting my arms up and bunching my shoulders so my muscles cramp—is often the newspaper, its heavy thump on the drive, the leaden headlines, the AP wire photographs of bombed buildings. From there it spreads, so that my life seems difficult. A daily walk becomes a burden instead of a gift. Instead of happily co-existing with my old dog, I begin worrying over him. Gratitude, another daily habit, is only one more chore.

arms up and bunching my shoulders so my muscles cramp—is often the newspaper, its heavy thump on the drive, the leaden headlines, the AP wire photographs of bombed buildings. From there it spreads, so that my life seems difficult. A daily walk becomes a burden instead of a gift. Instead of happily co-existing with my old dog, I begin worrying over him. Gratitude, another daily habit, is only one more chore.

In such a state, how lucky to have picked up this book by Nebraska poet Ted Kooser. From the back cover:

Great poetry, like Kooser’s, like Chekhov’s stories, is not sentimental, but it is characterized by a kind of tender wisdom communicated with absolute precision.

–Jonathan Holden, The North Dakota Quarterly

I have sung Kooser’s praises before, and so I won’t go on and on today (for two of them, see links here and here.) In brief, this book came about when Kooser was recovering from cancer surgery and radiation; he writes in the short preface:

During the previous summer, depressed by my illness, preoccupied by the routines of my treatment, and feeling miserably sorry for myself, I’d all but given up on reading and writing. Then, as autumn began to fade and winter came on, my health began to improve. One morning in November, following my walk, I surprised myself by trying my hand at a poem. Soon I was writing every day.

He walked before first light—his oncologist had told him to stay out of the sun for a year—and each day he wrote a short poem, pasted it onto a postcard, and sent it to his friend, writer Jim Harrison. What could be simpler? And how lucky are we, to have the record of these poems, a whole chain of 100, stepping stones, or a daily prescription to be taken, each made of close observation and (often) dazzling metaphor.

november 9

Rainy and cold.

The sky hangs thin and wet on its clothesline.

A deer of gray vapor steps through the foreground,

under the dripping, lichen-rusted trees.Halfway across the next field,

the distance (or can that be the future?)

is sealed up in tin like an old barn.—Ted Kooser

My work isn’t hard, not even this work of putting up a blog post each week. Read a book of poems. Share one poem. (I make it hard, by wanting the post to be a “real” review, but it needn’t be. Let’s call it an “appreciation,” a little celebration, sharing with my friends a book I enjoyed.)

Kooser’s postcard poems are about his walks, about reminiscences of his childhood, about his old dog, Hattie. They are made of homely things, bedsheets and sewing machines and birds. They are, like the birds, “full of joy.” The first poem (above) is from November 9 and they continue through March 20:

The vernal equinox.

How important it must be

to someone

that I am alive, and walking,

and that I am writing these poems.

This morning the sun stood

right at the end of the road

and waited for me.—Ted Kooser

So here I am, just past this year’s vernal equinox, with daffodils tipping back their heads and shouting into the rain. And here I am, with this book.

Photo by Tina Nord, via pexels.com

wrenching reminder of why the sea must be loved, cherished, and protected.” I agree.

wrenching reminder of why the sea must be loved, cherished, and protected.” I agree.

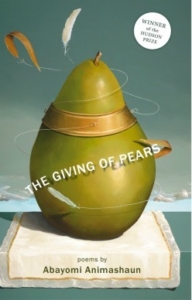

paper, texasreviewpress.org.

paper, texasreviewpress.org.