I wrote this little essay when my mother had been living in care for over a year. After four years in a care home, she has lost additional ground and is even more bedridden, and no longer speaking. I miss her loopy stories and the way her eyes used to brighten on seeing me, even when she didn’t know my name. So, I’ve decided to share this with you. Thanks for indulging me.

When I was in an MFA program for poetry, one of my professors chided me for my reliance on narrative, on story. “Stop making sense,” he advised.

When I was in an MFA program for poetry, one of my professors chided me for my reliance on narrative, on story. “Stop making sense,” he advised.

My mother was diagnosed with Alzheimer’s in 2011. My father had recently died, and Mom managed okay for a couple of years—but only with a lot of support from me and my youngest sister. Eventually we called in the clan to help and we moved Mom from the farmhouse where she was born in 1932, the house where her parents raised 14 kids, the house where my mom and dad raised their five children.

In her new apartment, she was able to hold onto most of her independence. At her insistence, she kept driving. (I kept borrowing her car, thinking maybe she’d forget that she had it—not at all a stretch of the imagination—but no such luck.) She had a small kitchen, but took dinner with the other residents in the main building, usually. She loved it when I came and spent the night. We could still watch Monk reruns on her television; we could still talk, even if she looped through the same stories again and again.

In the summer of 2014, however, all that changed. A stroke paralyzed her left side and plunged her into a world that my former poetry professor would have admired. In short, my mother stopped making sense.

When Mom first moved into a skilled-nursing facility, my sister and I kept trying to make sense of things for her. We moved Mom’s bed from the middle of her room to the side, thinking her line of sight (from her right side, the neurologist had explained) would be better. Maybe she’d watch TV again. She could read, and sometimes pointed out words. She still wore her glasses. But she didn’t read. I tried reading aloud one of her Agatha Christie novels, and she stared at me, puzzled and alarmed. Then said, “You got all of that, from in there?” Just as with moving the bed, reading aloud to her seemed another of our relentless attempts to make sense of what didn’t make sense.

Yesterday, Mom wanted to tell me about two horses. Not the horses of my childhood, at least it didn’t seem so, but maybe her brother’s horses from her childhood. I asked questions, but the conversation had taken the bit in its teeth and Mom was intent on the poetry of it. When I looked out her window, I saw green trees and rain. When she looked, everything was in bloom. She seemed to be riding farther and farther away from me.

It’s only because it’s late in the day, one of Mom’s caregivers told me. She’ll be better in the morning.

But this morning, Mom doesn’t know me at all. She is telling a story, however, that somehow includes my name. Bethany did this, Bethany did that…it’s hard to follow. “I’m Bethany,” I tell her after a while, and her eyes focus on me, wide with surprise. “I thought you were Evelyn,” she says. Evelyn, her dark-eyed, dark-haired sister (I am blonde, like my father). Evelyn, her older sister, walking with a cane the last time I saw her, but still with her wits pretty much about her.

Mom does get a little better as I coax her to eat lunch. She knows me now, if only to scold me. “I’m the mother,” she says. “Stop telling me what to do.”

“What do you want me to do?” I ask her, feeling elated, as though my mother is back in the room and ready to take charge. But, no. Mom turns her big-eyed, little-girl expression on me again and says, “Will you call my mother and tell her where I am?”

From time to time I have tried to embrace the stop-making-sense school of poetry. I like poems of all kinds, after all, even the absurd ones that spin a kind of magic spell over a reader, transporting us to another world. Mom’s world.

Tonight—home again—I get up at midnight, after my daughters have abandoned the living room. I turn on the TV and find a 73-minute movie called “A Poet in New York.” That title is all I have to go on, but I start the movie and discover that it is about Dylan Thomas. I think of my favorite poetry professor, not the “stop making sense one,” but a professor who liked my story-heavy, narrative poems. I think of how he adored Thomas. He could do a fair impersonation of him, with a swaggering, Welsh accent. “When I was young and easy under the apple boughs.” There is frightfully little of Thomas’s poetry in this movie. Mostly there is whiskey and sex and poor Caitlin Thomas’s mad passion for Dylan (he pronounces her name Cat-lin and writes her letters telling her how much he misses fondling her breasts). The movie does not make a lot of sense, but that, in itself, makes a kind of sense to me. Tonight it does.

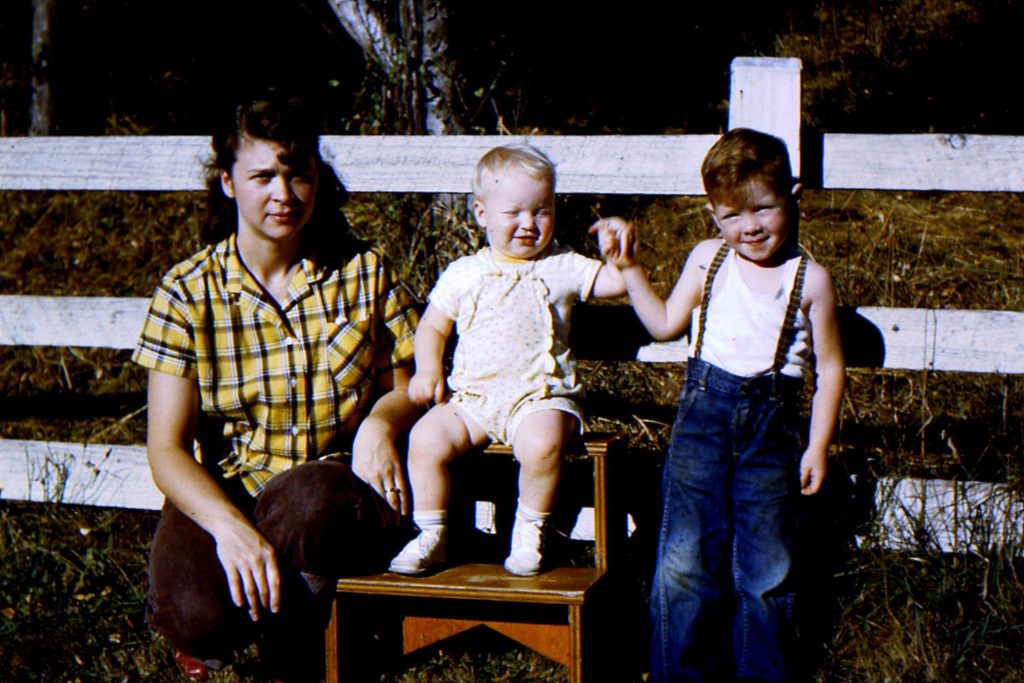

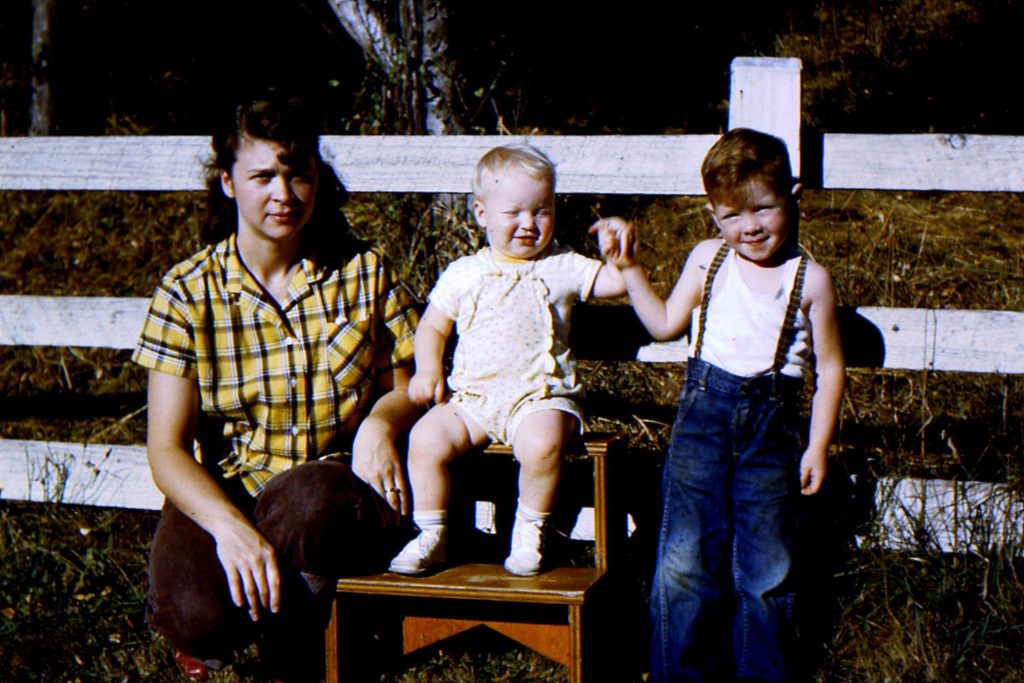

Mom, me, and my big brother Eric

Immediately after the stroke, while still in the hospital, Mom told me, “Bury me on the hill beside your father.” (My sister, hearing this exchange from the doorway, slapped her forehead and said, “Geez, I hadn’t thought of that!”) The slow slide into complete dependency—into nonsense—continues, though she no longer has to be reminded that she can’t get out of bed, or that she can’t walk. She no longer asks to be buried on the hillside.

In my mother’s non-narrative, non-linear mind, of course she can walk. She is a child, running through a field (and I picture the young Dylan Thomas running through a field of tall grass). Her brother’s horses spook and wheel and she runs after them. This is the world, too, of the poem. We want to make sense of it. But we might allow ourselves a little more rein to be in the non-sense. To take the poem’s hand, and run with it.

How did my daughters get so old?

How did my daughters get so old?

When I was in an MFA program for poetry, one of my professors chided me for my reliance on narrative, on story. “Stop making sense,” he advised.

When I was in an MFA program for poetry, one of my professors chided me for my reliance on narrative, on story. “Stop making sense,” he advised.

This morning — around 10:00 — I went to Staples and printed out my novel manuscript. I meant to take it home and give it to my beloved (he’s my final proofreader), but instead I went to Barnes & Noble and started reading. I have been reading all day! It’s good, I think it’s good. But I also finally — FINALLY — figured out my character Hannah and how she contrasts (and doesn’t merely mirror) the main character. So I had lots of little changes. And I’m almost all the way through. I’m so happy!

This morning — around 10:00 — I went to Staples and printed out my novel manuscript. I meant to take it home and give it to my beloved (he’s my final proofreader), but instead I went to Barnes & Noble and started reading. I have been reading all day! It’s good, I think it’s good. But I also finally — FINALLY — figured out my character Hannah and how she contrasts (and doesn’t merely mirror) the main character. So I had lots of little changes. And I’m almost all the way through. I’m so happy!