If you’re following this blog, there must be a part of you that wants to write, or wants to write more.

It’s hard to go from a wish to a new reality, but it is possible.

Several years ago, I had not only a full-time teaching job, but also a houseful of kids (my twins were probably about 16 and always had friends over; my youngest would have been 10, and ditto). And, somehow, to my great dismay, I was 40 pounds overweight. I wished–fervently–that I could have back my old, lean and fit self. But I felt completely helpless to change. I was too busy to do anything differently. Wasn’t I?

In the lunchroom at the college one day, I wondered aloud if I was going to gain 5 or 10 pounds a year every year until …what? … until I could no longer move?

I am not going to bore you with all the details of how I changed that belief, and how long it took (not in this blog post, anyway), but I do want to share a crucial first step.

It started with a dream.

And I mean a real, night-time, epic dream. In this dream I wasn’t younger, not some old “ideal” self. I was my age at the time (50-something), and it was by no means a fantasy self either–no bikinis here. But in this dream I was thin, and I was packing a suitcase and preparing to go somewhere on an adventure.

When I woke up, I did not think, “Oh, that was nice. If only!” Rather, I felt as though I had been hanging out with MY REAL SELF. I knew that the woman I saw in the dream was ME. Real me; not pudgy, too-busy-to-exercise me. I shifted–I began to think of myself as a healthy person. I started to make different choices–nothing big (I still didn’t have a lot of time on my hands), but small, daily choices. What would thin/fit Bethany do?

In the more than five years since then, I have not forgotten that dream. For me this little story demonstrates something that I think we all already know–at some level–about goal-setting. It starts with a vision–an image that goes way beyond all the advertising we’re bombarded with. It’s about making a conscious choice (out of the many choices) and imagining it fully.

Imagination is more important than knowledge. For knowledge is limited, whereas imagination embraces the entire world, stimulating progress, giving birth to evolution.” –Albert Einstein

Of course it doesn’t have to come to you like a vision or a night-time dream, but it’s pretty clear to me that my dream triggered for me a shift in who I pictured myself to be.

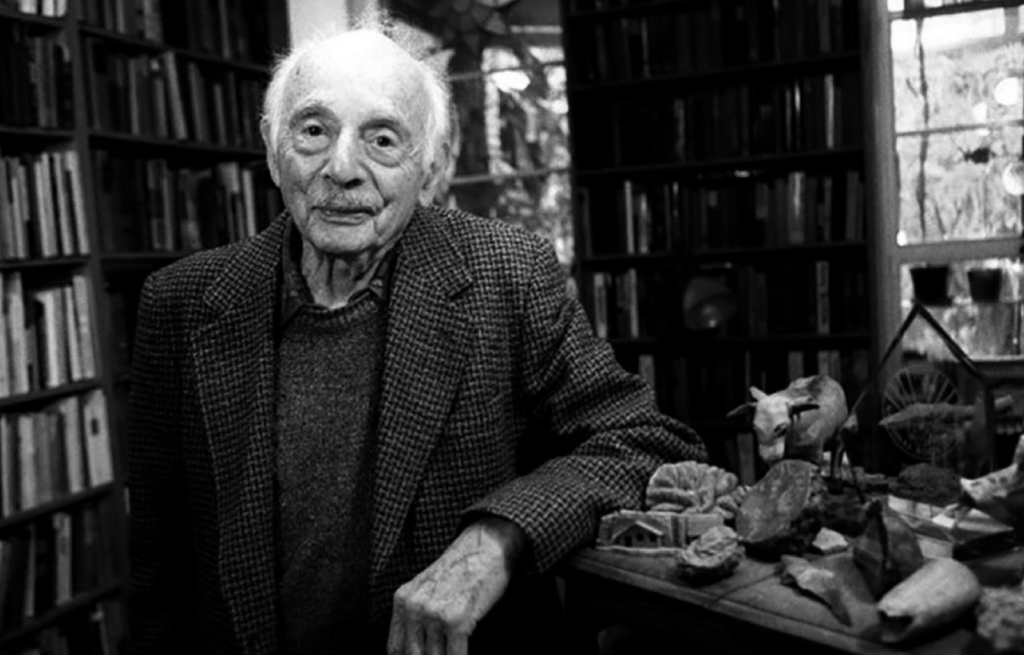

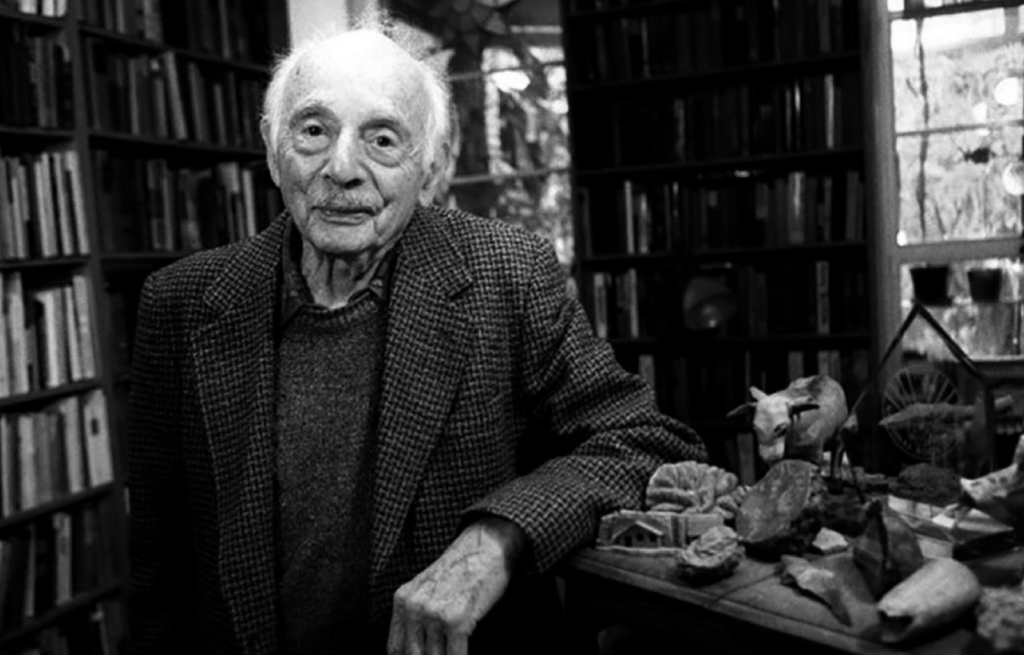

I’m reminded of my dear poetry professor, Nelson Bentley, who said over and over again to his eager little poets: “You must fully imagine!” That’s exactly what I did. I’m reminded, too, of a line we used back in my restaurant days to get ourselves pumped up: If you can conceive it, you can achieve it.

Mary Morrissey, a motivational coach I listen to, talks about this at length: Everything is created twice. Before the chair you are sitting in came into being, someone imagined it.

If you want to change something–or to reset something (like resetting my personal image to my more energetic self)–it will help you so much if you can PICTURE what it is you want.

This is your writing assignment today.

Your job is to really really picture what success will look like for your writing. It does not have to be big; in fact, there is good reason to make it small. My go-to mantra for writing, when my kids were young, was simply, “I write every day,” which I then had to do to make true. Five minutes was enough to make it so.

In this assignment, be POSITIVE and CLEAR. In my dream, for instance, I was holding a pair of size 4 shorts, ready to put them in a suitcase. I looked at them and thought, Should I pack these? Can I really fit into them? And dream-self said, YES.

For the record, you can do this and still remain the anti-affirmation, anti-woo-woo person you are. I have no interest whatsoever in being 20 again, or looking 20 (or 40, for that matter). When I was working on my bigger WHY for getting fit, I wasn’t looking up plastic surgeons. I was thinking of someone a little like my Aunt Aronda, my mother’s older sister, who even at 94 was still a sharp wit, good with a jigsaw puzzle, still reading books (if not writing them) and if not as fit as I want to be at that age, pretty dang close.

I also thought of the poet Stanley Kunitz, who was still giving poetry readings at age 100.

Do I have control over how long I live? No, I don’t. But do I have control over what I do today–and, right now? Yeah, pretty much.

Can you come up with a solid, tangible picture of what you want? (Is it a magazine publication? A finished and printed poem you can share at your next lunch with a friend? A blog? A book? You, standing in front of an audience? You, being interviewed on PBS? Your future granddaughter reading the book that you wrote about your year in Tibet?)

What does your writing dream look like?

Write that. I’d love to hear about it!

It’s here!

It’s here!