Rabbi Alfred Bettleheim once said: “Prejudice saves us a painful trouble, the trouble of thinking.” – Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Rabbi Alfred Bettleheim once said: “Prejudice saves us a painful trouble, the trouble of thinking.” – Ruth Bader Ginsburg

I have been trying, not entirely successfully, to wrap my head around all that’s swirling around us in 2020. There’s the pandemic, of course, and there’s the resurgence of Black Lives Matter–both, to my mind, more than worthy of our attention. Then wildfires, extreme weather, climate change hit the news headlines, and the furor over the coming election becomes even more heated.

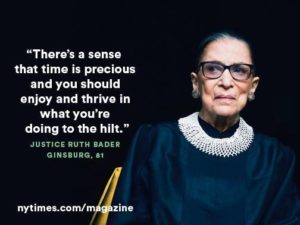

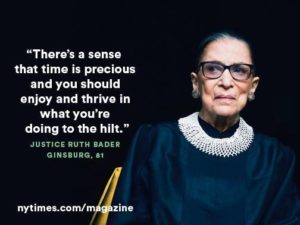

With Justice Ruth Bader Ginsberg’s death, the political turmoil that our country is going through seems even more exaggerated, and more divided. Because many people in my family of origin are on the opposite side of this divide from me, all of it is a source of deep, personal anguish.

I try to read widely and deeply, to think my own thoughts and be clear about what I believe. But, under these circumstances, it gets murky and I am as apt as anyone to lose my way.

“Why be a poet now?” I asked a friend. “What’s the point?” She said, “If RBG were a poet, she’d be the best damn poet. That’s what you should do.”

This morning I read this tribute in The Seattle Times, “Clerking for Justice Ginsberg We Learned about Law–and Love,” by Miriam Seifter and Robert Yablon. It says it all:

“The justice kept up her relentless pace because she believed in her work and in doing the job right.”

And in my email feed yesterday, I found this message from Richard Rohr, author of Falling Upward: A Spirituality for the Two Halves of Life, and many other books. He helped me and maybe his words will help you, too. I’m attempting to share, via this link — but just in case the link doesn’t work, I’ve pasted it in below:

Some simple but urgent guidance to get us through these next months.

I awoke on Saturday, September 19, with three sources in my mind for guidance: Etty Hillesum (1914 – 1943), the young Jewish woman who suffered much more injustice in the concentration camp than we are suffering now; Psalm 62, which must have been written in a time of a major oppression of the Jewish people; and the Irish Poet, W.B.Yeats (1965 – 1939), who wrote his “Second Coming” during the horrors of the World War I and the Spanish Flu pandemic.

These three sources form the core of my invitation. Read each one slowly as your first practice. Let us begin with Etty:

There is a really deep well inside me. And in it dwells God. Sometimes I am there, too … And that is all we can manage these days and also all that really matters: that we safeguard that little piece of You, God, in ourselves.

—Etty Hillesum, Westerbork transit camp

Note her second-person usage, talking to “You, God” quite directly and personally. There is a Presence with her, even as she is surrounded by so much suffering.

Then, the perennial classic wisdom of the Psalms:

In God alone is my soul at rest.

God is the source of my hope.

In God I find shelter, my rock, and my safety.

Men are but a puff of wind,

Men who think themselves important are a delusion.

Put them on a scale,

They are gone in a puff of wind.

—Psalm 62:5–9

What could it mean to find rest like this in a world such as ours? Every day more and more people are facing the catastrophe of extreme weather. The neurotic news cycle is increasingly driven by a single narcissistic leader whose words and deeds incite hatred, sow discord, and amplify the daily chaos. The pandemic that seems to be returning in waves continues to wreak suffering and disorder with no end in sight, and there is no guarantee of the future in an economy designed to protect the rich and powerful at the expense of the poor and those subsisting at the margins of society.

It’s no wonder the mental and emotional health among a large portion of the American population is in tangible decline! We have wholesale abandoned any sense of truth, objectivity, science or religion in civil conversation; we now recognize we are living with the catastrophic results of several centuries of what philosophers call nihilism or post-modernism (nothing means anything, there are no universal patterns).

We are without doubt in an apocalyptic time (the Latin word apocalypsis refers to an urgent unveiling of an ultimate state of affairs). Yeats’ oft-quoted poem “The Second Coming” then feels like a direct prophecy. See if you do not agree:

Turning and turning in the widening gyre

The falcon cannot hear the falconer;

Things fall apart; the centre cannot hold;

Mere anarchy is loosed upon the world,

The blood-dimmed tide is loosed, and everywhere

The ceremony of innocence is drowned;

The best lack all conviction, while the worst

Are full of passionate intensity.

Somehow our occupation and vocation as believers in this sad time must be to first restore the Divine Center by holding it and fully occupying it ourselves. If contemplation means anything, it means that we can “safeguard that little piece of You, God,” as Etty Hillesum describes it. What other power do we have now? All else is tearing us apart, inside and out, no matter who wins the election or who is on the Supreme Court. We cannot abide in such a place for any length of time or it will become our prison.

God cannot abide with us in a place of fear.

God cannot abide with us in a place of ill will or hatred.

God cannot abide with us inside a nonstop volley of claim and counterclaim.

God cannot abide with us in an endless flow of online punditry and analysis.

God cannot speak inside of so much angry noise and conscious deceit.

God cannot be found when all sides are so far from “the Falconer.”

God cannot be born except in a womb of Love.

So offer God that womb.

Stand as a sentry at the door of your senses for these coming months, so “the blood-dimmed tide” cannot make its way into your soul.

If you allow it for too long, it will become who you are, and you will no longer have natural access to the “really deep well” that Etty Hillesum returned to so often and that held so much vitality and freedom for her.

If you will allow, I recommend for your spiritual practice for the next four months that you impose a moratorium on exactly how much news you are subject to—hopefully not more than an hour a day of television, social media, internet news, magazine and newspaper commentary, and/or political discussions. It will only tear you apart and pull you into the dualistic world of opinion and counter-opinion, not Divine Truth, which is always found in a bigger place.

Instead, I suggest that you use this time for some form of public service, volunteerism, mystical reading from the masters, prayer—or, preferably, all of the above.

You have much to gain now and nothing to lose. Nothing at all.

And the world—with you as a stable center—has nothing to lose.

And everything to gain.

Richard Rohr, September 19, 2020

Rabbi Alfred Bettleheim once said: “Prejudice saves us a painful trouble, the trouble of thinking.” – Ruth Bader Ginsburg

Rabbi Alfred Bettleheim once said: “Prejudice saves us a painful trouble, the trouble of thinking.” – Ruth Bader Ginsburg