Today’s post is even more like an interview than a review. I have three of Kathleen Kirk’s chapbooks—little poetry  books that address a single subject—and when I learned that The Towns (Unicorn Press, 2018) is actually one of eight poetry chapbooks, “each one a bit different in its impetus, composition, and arrangement,” I knew that I wanted to hear more.

books that address a single subject—and when I learned that The Towns (Unicorn Press, 2018) is actually one of eight poetry chapbooks, “each one a bit different in its impetus, composition, and arrangement,” I knew that I wanted to hear more.

I did know a bit about Kathleen’s background, as I reviewed her ABCs of Women’s Work last April. But I’ll let people do their own spelunking into her background: check out Escape Into Life, an on-line magazine of literature and art, where she is the editor, or her (delightful) blog—Wait! I have a blog?!—to learn much, much more.

This year I emailed Kathleen and asked her to tell me about her books and how she creates them. I had fun looking up the presses (of course Unicorn=unique books!), and am including the links so you can take a tour, too.

Nocturnes (Hyacinth Girl Press, 2012) captured a bunch of poems set at night, and often musical in quality (like musical nocturnes) or responding to night time paintings. Living on the Earth (Finishing Line Press, New Women’s Voices Series No. 74, 2010) gathered poems of place I was exploring after returning to live where I’d grown up, and in the context of worrying about and valuing our dear planet. An earlier chapbook, Broken Sonnets (Finishing Line, 2009), contained and celebrated my awareness of being “broken” but perfectly okay in sonnets that respected but also broke traditional forms of the sonnet. I guess I knew I was done when I’d broken the form in all the ways I could at that time.

Interior Sculpture: poems in the voice of Camille Claudel (dancing girl press, 2014) was a commissioned work, providing poems to create a dance/theatre piece, and I pursued Camille Claudel’s biography and work to voice a series of poems set to dance, and a few more.

In Spiritual Midwifery (Red Bird, 2019), I found I was gathering from a series of ekphrastic poems I’d been writing, often on paintings with religious topics, as well as poems on how life itself had engendered in me a personal spirituality, enhanced by motherhood; the poems clung to each other on their own—again, probably instinct and logic, as that chapbook ends with a poem called “Last Step.” My very first chapbook, Selected Roles (Moon Journal Press, 2006) is the bridge between my life as a professional actor in Chicago and my organic life as a poet. In these poems, I speak in the voices of characters I have played or in the persona of an actor playing those roles.

I am still looking for a home for my chapbook manuscript The Cassandra Poems, in which I speak in the voice of Cassandra, the mythological character and the character in Agamemnon, the play by Aeschylus, as if she were still alive today, a prophetess whom no one will believe, which, as a poet, I feel like lots of the time. Most of these poems have been published individually in journals, and a couple new ones are due out soon in Levitate, but I would love to see them all together in a chapbook.

I have not lived abroad, as Kathleen has, but I have spent a lot of time in small, western towns—and of course I’ve read one of Kathleen’s influences, The Triggering Town, by Richard Hugo. Another influence was The Outlaw Years, by Robert M. Coates, about outlaws along the Natchez Trace. Kathleen explains:

Outlaws might yearn for towns without being able to belong to them, because they are outside the boundaries of the law. I found I was writing poems based on [poems of] Richard Hugo and Theodore Roethke…involving repeated words and images. I applied the form restrictions to small towns and outlaws alike, to see what would happen!

To put her books together, Kathleen relies on “1) instinct 2) logic, a paradoxical juxtaposition.” In The Towns she used town names in the titles, particularly at the beginning of the book, “to root us in place.” The outlaws are introduced early, and sort of take over as the poems progress, putting us “outside the boundaries.” The logic of ending with “The Last Word” is hard to refute.

I got to do the release reading for The Towns at Ryburn Place, a shop and visitor center run by Terri Ryburn in the renovated Sprague Super Service gas station along old Route 66, in front of a map where I could point to several of the towns in my poems on or just off Route 66! Other towns in the book are elsewhere in the Midwest or in the American South, and “The Towns” (the title poem) is a mini-autobiography via all the towns and cities I’ve lived in, which also goes to Europe and comes home again. I always cry reading that one out loud, because it comes back to small-town cemeteries.

Photo by Malte Luk from Pexels

The Towns is comprised of 15 poems. Outlaws recur, town names, obviously, but there’s also a kind of intrusion of the natural world into every poem–and, I admit, it’s that element that grabs me every time. In “Beason,” we feast on a series of almost-disjointed images (I had a sense of flipping through a series of postcards), the poet/persona is the outlaw, breaking boundaries, or she’s the “outlaw” deer:

Beason

That upstairs window has a woman in it,

or a dress-form. That door is falling off

because a deer walked right up the porch

steps and knocked. I don’t know much

about the town of Beason, except what

I’m not saying, but I know enough to bite

the hand that feeds me this mango, its

hard pit knocking against my teeth

a modified Morse code for love.

It’s possible he’ll leave me here

in Beason at this little lake

where I turn to drop my empty cup

in the rusty can; he’ll run off

in his car, abandon me to the geese.

If he does, I can walk determined

up the road to the nearest mailbox

and right on up the porch steps

to knock, wild-eyed and alive.

—Kathleen Kirk

The Consequences of My Body by Maged Zaher is a series of untitled lines and prose paragraphs that (sometimes) appear to be letters (once to “Z,” others to “X” and “Y”). Thoughts on love are peppered throughout—“I am a descendent of ‘Udhri:’ Arab love poets”—and thoughts on poetry itself:

The Consequences of My Body by Maged Zaher is a series of untitled lines and prose paragraphs that (sometimes) appear to be letters (once to “Z,” others to “X” and “Y”). Thoughts on love are peppered throughout—“I am a descendent of ‘Udhri:’ Arab love poets”—and thoughts on poetry itself:

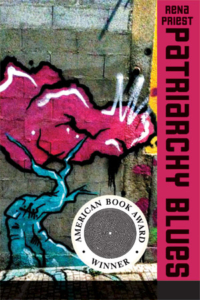

I couldn’t have been more thrilled to hear that

I couldn’t have been more thrilled to hear that  Patriarchy Blues was published by

Patriarchy Blues was published by

books that address a single subject—and when I learned that The Towns (

books that address a single subject—and when I learned that The Towns (

Poem, Revised, edited by Robert Hartwell Fiske and Laura Cherry (Marion St. Press, 2008), collects 50+ essays by poets about their revision process of a specific poem. Mark Vinz’s poem “The Penitent” began as prose, an attempt to get down on paper a memory that had come to him on a sleepless night. It went through many drafts before it appeared in Prairie Schooner. He cites another much-loved poetry book on my shelf:

Poem, Revised, edited by Robert Hartwell Fiske and Laura Cherry (Marion St. Press, 2008), collects 50+ essays by poets about their revision process of a specific poem. Mark Vinz’s poem “The Penitent” began as prose, an attempt to get down on paper a memory that had come to him on a sleepless night. It went through many drafts before it appeared in Prairie Schooner. He cites another much-loved poetry book on my shelf: Chicago Press, 1968). I’ve been reading a few pages a day of this book and, initially, I wasn’t sure it would be helpful (much emphasis on centuries-old poems). But it has won me over.

Chicago Press, 1968). I’ve been reading a few pages a day of this book and, initially, I wasn’t sure it would be helpful (much emphasis on centuries-old poems). But it has won me over. likely going to be passed along to her: What Is Poetry: The Essential Guide to Reading & Writing Poems, by Michael Rosen (Candlewick Press, 2016).

likely going to be passed along to her: What Is Poetry: The Essential Guide to Reading & Writing Poems, by Michael Rosen (Candlewick Press, 2016).