Solmaz Sharif: Customs

CUSTOMS: POEMS, Solmaz Sharif. Graywolf Press, 250 Third Avenue, Suite 600, Minneapolis, MN 55401, 94 pages, $16 paper, www.graywolfpress.org.

This morning I read Customs, the brand new book of poems by Solmaz Sharif, and I read the interview in the March/April issue of Poets & Writers, and the review in my copy of the March 21, 2022, The New Yorker.

If you are interested in poetry today, this is a poet to watch. Reading the  opening paragraph of the NYer article, I thought of William Carlos Williams: “It is hard to get the news from poems / but men die miserably every day / for lack of what is found there.”

opening paragraph of the NYer article, I thought of William Carlos Williams: “It is hard to get the news from poems / but men die miserably every day / for lack of what is found there.”

The title of Solmaz Sharif’s second book of poems….evokes the extended “if” of someone enmeshed in the sadistic bureaucracy of American immigration, a person at the mercy of an “officer deciding by blood sugar, last blow job received, and relative level of disdain for vermin” who belongs and who does not. Anyone whose presence is conditional knows that a time will come when the conditions will not be met. To be let in, as Sharif—who was born in Turkey to Iranian parents and is a naturalized citizen of the United States—writes, is inevitably to be “let in until.” In these poems, the ostensible clarity of borders and checkpoints gives way to a terrain of fundamental uncertainty, a geography of elusive thresholds, delayed arrivals, and impossible returns.

–Elisa Gonzalez, The New Yorker, March 21, 2022

To emend Gonzalez’s paragraph, the poem “He, Too,” quoted here doesn’t end with a period but leaves us in empty space:

I am let in until

We’re left dangling, as Sharif, making her way through a customs officer—who wants to know (among other intrusive questions) what she teaches, only to reply, “I hate poetry“—leaving her in doubt as to her own belongingness, or her ability to belong anywhere. In the middle section of the book, too, an extended riff on the preposition of plays similarly with white space and closure, this time adding end brackets (never open brackets, as the NYer article points out).

Of is the thing without which

I would not be.]]

Of which I am without

or away from.

I am without the kingdom]]

and thus of it.

I’m not replicating this excerpt exactly; there’s more white space. The poem occupies 20 pages, some of them almost entirely blank. It ends with a black page. It’s a book you have to hold in your hands and physically experience.

In the Poets & Writers interview, Douglas Kearney quotes another poet, his friend Yona Harvey, as saying “I’m not writing for awards. I’m trying to get my soul ready.” Sharif responds by talking about wholeness: “I suppose the only thing that is possible is wholeness, that any kind of hacking—that’s the illusion. But as a writer I care for the hacked things, in their illusory hackedness, and what it might mean to name, very smally, the seemingly aborted or disdained or broken things that feel incomplete or irrelevant” (p. 43).

She continues:

I appreciate, too, the word integrity. I’m realizing that that’s the central word of my practice. How do I live with integrity? I’ve wondered that, politically and ethically, for a very long time, and now a part of it is “How do I live with a spiritual integrity?” Also I love that: “Get my soul ready.” How to know how to get out of the way of things I don’t yet know how to articulate or how it lines up politically with everything I’ve done so far—but if I know it to be true and I know its intention is not to harm, then it is my job to live with integrity toward it and in naming it. (p. 43)

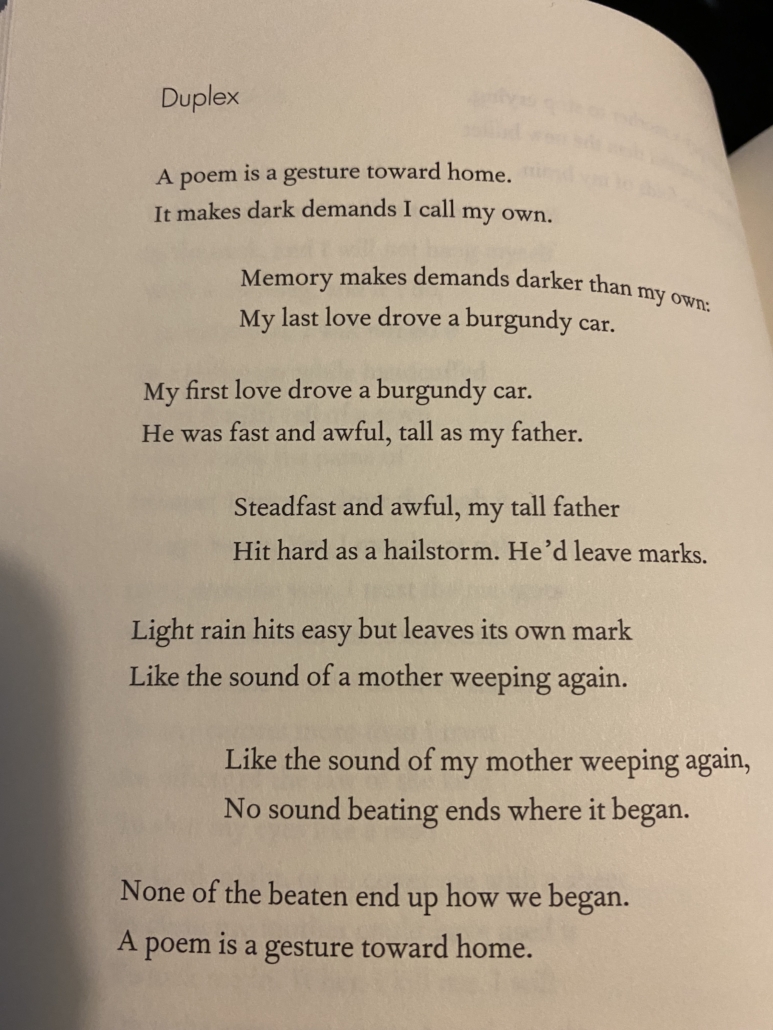

And here’s a poem that, at first glance, seems deceptively simple, or named “smally,” as Sharif might describe it, the first poem in the book:

Dear Aleph,

Like Ovid: I’ll have no last words.

This is what it means to die

among barbarians. Bar bar bar

was how the Greeks heard

our speech—sheep, beasts—and so we became

barbarians. We make them reveal

the brutes they are by the things

we make them name. David,

they tell me, is the one

one should aspire to, but ever since

I first heard them say Philistine

I’ve known I am Goliath

if I am anything.—Solmaz Sharif

Before I leave this, I want to add that Sharif would argue with my use of the Williams quote above (“It’s hard to get the news…”). To quote from the NYer article:

Rejecting the injunction to bear witness, [Sharif] displays a thrilling contempt for literature’s vaunted ability to elicit empathy, which means only “laying yourself down / in someone else’s chalklines/and snapping a photo.” For Sharif, the chalk lines around a body, like the borderlines around a body politic, are another boundary not to be trusted; the contours of personal experience can’t describe, literally or literarily, the truth of a trauma.

—Elisa Gonzalez

To my mind, this is news we need to hear.

You can read more about Sharif, and more poems, too, at Poetry Foundation, and https://www.solmazsharif.com and … well, everywhere.

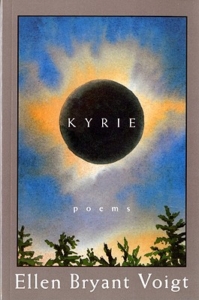

couldn’t differ more from Seuss’s Frank. Well, maybe there’s a correlation in that both collections tell a dark story. Voigt is telling, however, not a personal story, but one set during the flu pandemic of 1918-1919.

couldn’t differ more from Seuss’s Frank. Well, maybe there’s a correlation in that both collections tell a dark story. Voigt is telling, however, not a personal story, but one set during the flu pandemic of 1918-1919.

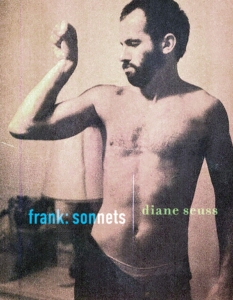

narrative test the boundaries of the conventional form” (Terrance Hayes). “…an ambitious, searing, and capacious life story. The poems themselves use an ecstatic syntax to unite Seuss’s lyric leaps from one wretched sweetness to another….narratives of poverty, death, parenthood, addiction, AIDS, and the ‘dangerous business’ of literature are irreducible” (Traci Brimhall). In short, it was a little like reading a memoir—bizarre, fragmented, mesmerizing. When I first purchased this book and read a poem here and there, I was missing the point.

narrative test the boundaries of the conventional form” (Terrance Hayes). “…an ambitious, searing, and capacious life story. The poems themselves use an ecstatic syntax to unite Seuss’s lyric leaps from one wretched sweetness to another….narratives of poverty, death, parenthood, addiction, AIDS, and the ‘dangerous business’ of literature are irreducible” (Traci Brimhall). In short, it was a little like reading a memoir—bizarre, fragmented, mesmerizing. When I first purchased this book and read a poem here and there, I was missing the point.

days. Reading all the poems is one thing, but rereading, thumbing back through, making notes, reflecting—those take a little more time.

days. Reading all the poems is one thing, but rereading, thumbing back through, making notes, reflecting—those take a little more time.