May Swenson (1913-1989)

“The poem is an eyehole to a kind of truth or beauty that is finally unnameable.” –May Swenson

Last week I visited Washington University in St. Louis, MO, and, among other pleasurable tasks, I spent two mornings in the Special Collections section of the Olin Library, pawing through the May Swenson archives.

Last week I visited Washington University in St. Louis, MO, and, among other pleasurable tasks, I spent two mornings in the Special Collections section of the Olin Library, pawing through the May Swenson archives.

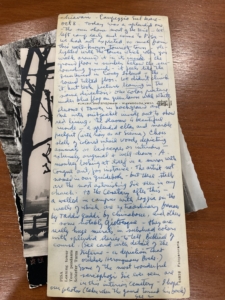

These are an example of her postcard journal—a stunning practice that I’d like to write more about, and adopt on my own

peregrinations.

peregrinations.

Many years ago—as a freshman in college—I encountered her poem, “The Centaur,” and though her work is varied and eclectric (and electric) and vast, this one poem is as good a place to begin as any.

The Centaur

The summer that I was ten—

Can it be there was only one

summer that I was ten? It musthave been a long one then—

each day I’d go out to choose

a fresh horse from my stablewhich was a willow grove

down by the old canal.

I’d go on my two bare feet.But when, with my brother’s jack-knife,

I had cut me a long limber horse

with a good thick knob for a head,and peeled him slick and clean

except a few leaves for the tail,

and cinched my brother’s beltaround his head for a rein,

I’d straddle and canter him fast

up the grass bank to the path,trot along in the lovely dust

that talcumed over his hoofs,

hiding my toes, and turninghis feet to swift half-moons.

The willow knob with the strap

jouncing between my thighswas the pommel and yet the poll

of my nickering pony’s head.

My head and my neck were mine,yet they were shaped like a horse.

My hair flopped to the side

like the mane of a horse in the wind.My forelock swung in my eyes,

my neck arched and I snorted.

I shied and skittered and reared,stopped and raised my knees,

pawed at the ground and quivered.

My teeth bared as we wheeledand swished through the dust again.

I was the horse and the rider,

and the leather I slapped to his rumpspanked my own behind.

Doubled, my two hoofs beat

a gallop along the bank,the wind twanged in my mane,

my mouth squared to the bit.

And yet I sat on my steedquiet, negligent riding,

my toes standing in the stirrups,

my thighs hugging his ribs.At a walk we drew up to the porch.

I tethered him to a paling.

Dismounting, I smoothed my skirtand entered the dusky hall.

My feet on the clean linoleum

left ghostly toes in the hall.Where have you been? said my mother.

Been riding, I said from the sink,

and filled me a glass of water.What’s that in your pocket? she said.

Just my knife. It weighted my pocket

and stretched my dress awry.Go tie back your hair, said my mother,

and Why is your mouth all green?

Rob Roy, he pulled some clover

as we crossed the field, I told her.—May Swenson

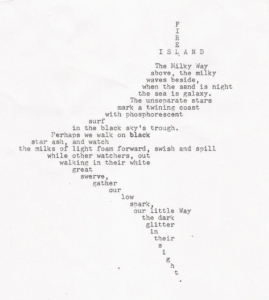

For this blogpost, I pulled the quote and the poem from my copy of Swenson’s Collected Poems (The Library of America , ed. Langdon Hammer, 2013). A quick Internet search for “May Swenson books” brought up numerous used copies of her many books. If you don’t know this poet at all, she’s especially well known for writing about the body—or “the animal body”—of which the human is one, and she is also known for her poems that play with shape and form, such as this:

I hope to circle back and share more—or offer a class. We’ll see!

And — this is a p.s. — you can take a peek at the Charles Johnson or David Wagoner archives by visiting https://humanities.wustl.edu/features/joel-minor-charles-johnson-magic-his-hands.

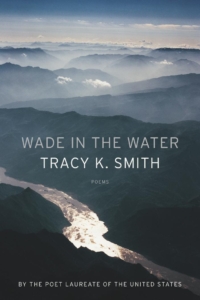

contemporary moment both to our nation’s fraught founding history and to a sense of the spirit, the everlasting. Here, private utterance becomes part of a larger choral arrangement as the collection includes erasures of the Declaration of Independence and correspondence between slave owners, a found poem composed of evidence of corporate pollution and accounts of near-death experiences, a sequence of letters written by African Americans enlisted in the Civil War, and the survivors’ reports of recent immigrants and refugees. Wade in the Water is a potent and luminous book by one of America’s essential poets.

contemporary moment both to our nation’s fraught founding history and to a sense of the spirit, the everlasting. Here, private utterance becomes part of a larger choral arrangement as the collection includes erasures of the Declaration of Independence and correspondence between slave owners, a found poem composed of evidence of corporate pollution and accounts of near-death experiences, a sequence of letters written by African Americans enlisted in the Civil War, and the survivors’ reports of recent immigrants and refugees. Wade in the Water is a potent and luminous book by one of America’s essential poets.

collection, but busy, too—like a care-taking daughter—with minutiae. Doctor appointments, dust, hospital rooms, post-it notes nudging a failing memory, loss.

collection, but busy, too—like a care-taking daughter—with minutiae. Doctor appointments, dust, hospital rooms, post-it notes nudging a failing memory, loss.

Then I stumbled across this one, sat down, and read it all the way through. Arthur Sze has long been one of my favorite poets, and Sight Lines is a book I already knew well. I’ve studied the poems and shared them with my writing group. But reading the whole book, all in one go, was a very different experience. (I recommend both approaches.)

Then I stumbled across this one, sat down, and read it all the way through. Arthur Sze has long been one of my favorite poets, and Sight Lines is a book I already knew well. I’ve studied the poems and shared them with my writing group. But reading the whole book, all in one go, was a very different experience. (I recommend both approaches.)