Give Thanks

The Books I’m Thankful for Today

one

In October I enrolled in another Hugo House poetry class, again with the amazing poet, translator, and teacher Deborah Woodard. The class focused on the work of Fernando Pessoa, born in Lisbon in 1888. Our main text, Fernando Pessoa & Co., edited and translated by Richard Zenith, gathers together work by Pessoa and three of his heteronyms, Alberto Caeiro,  Ricardo Reis, and Álvaro de Campos. Pessoa created entire biographies for these alter-egos and considered them mentors and colleagues. He is, Zenith tells us, “an editor’s nightmare,” but also a treasure trove:

Ricardo Reis, and Álvaro de Campos. Pessoa created entire biographies for these alter-egos and considered them mentors and colleagues. He is, Zenith tells us, “an editor’s nightmare,” but also a treasure trove:

Pessoa published relatively little and left only a small percentage of the rest of his huge output—over 25,000 manuscripts have survived—in anything close to a finished state. The handwritten texts, which constitute the vast majority, tend to teeter on the brink of illegibility, requiring not just transcription but decipherment. (Richard Zenith)

Pessoa prided himself on being impersonal, even invisible, a crossroads where observations took place. He deplores philosophy and metaphysics. I had difficulty caring about him for almost the entire stretch of the course. But…as usual…as I read and considered (and attempted to write my own poems), I began to feel curious about this poet, writing in another language, in another time, and living in a place I have never been. I have a feeling Pessoa would have approved of my journey, both the reticence and the curiosity.

Here is one piece, from the section titled “Uncollected Poems”:

It is night. It’s very dark. In a house far away

A light is shining in the window.

I see it and feel human from head to toe.

Funny how the entire life of the man who lives there, whoever he is,

Attracts me with only that light seen from afar.

No doubt his life is real and he has a face, gestures, a family and profession,

But right now all that matters to me is the light in his window.

Although the light is only there because he turned it on,

For me it is immediate reality.

I never go beyond immediate reality.

If I, from where I am, see only that light,

Then in relation to where I am there is only that light.

The man and his family are real on the other side of the window,

But I am on this side, far away.

The light went out.

What’s it to me that the man continues to exist?

He’s just the man who continues to exist.8 November 1915

Alberto Caeiro

two

I’ve been reading—or reading around in—another strange book, this one titled The Ashley Book of Knots. It was written and illustrated (3384 numbered illustrations) by Clifford W. Ashley, and first published in 1944. My copy belonged to my paternal grandfather (a Navy Seabee during WWII, which must explain why the book looks so well-read; I could go on a bit about my grandfather—as he was in his 40s and had 5 children when he enlisted; he kept his paychecks [from what I’m told], but wrote letters home signed, “Your poet, Gene”). His name and the date, Eugene H. King, 10/14/46, are written on the inside front cover. I can guess that the book came to belong to my father in 1959, when his father died. Since 2012, it has been mine, and this year I finally took it down from the shelf.

I’ve been reading—or reading around in—another strange book, this one titled The Ashley Book of Knots. It was written and illustrated (3384 numbered illustrations) by Clifford W. Ashley, and first published in 1944. My copy belonged to my paternal grandfather (a Navy Seabee during WWII, which must explain why the book looks so well-read; I could go on a bit about my grandfather—as he was in his 40s and had 5 children when he enlisted; he kept his paychecks [from what I’m told], but wrote letters home signed, “Your poet, Gene”). His name and the date, Eugene H. King, 10/14/46, are written on the inside front cover. I can guess that the book came to belong to my father in 1959, when his father died. Since 2012, it has been mine, and this year I finally took it down from the shelf.

I’m working on a little chapbook of poems (at least I think it’s a chapbook) to turn in for my Hugo House class project. I’ve titled it “Keeper of Knots,” after Caeiro’s The Keeper of Sheep. (Which begins: “I’ve never kept sheep / But it’s as if I did.”)

three

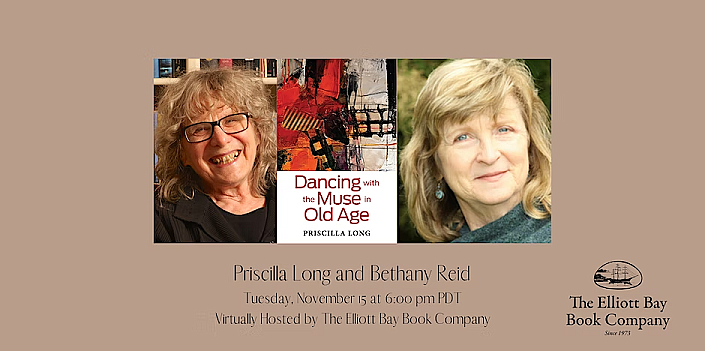

I’m immensely grateful to have been able to join Priscilla Long for the Elliott Bay Zoom / Eventbrite launch of her new  book, Dancing with the Muse in Old Age. After losing my father at age 82 to a stroke; after accompanying my mother through ten years of Alzheimer’s, stroke, and skilled-nursing care, then her death at age 86; I had pretty much decided that I’d better get things done right now, because I would be decrepit very very soon.

book, Dancing with the Muse in Old Age. After losing my father at age 82 to a stroke; after accompanying my mother through ten years of Alzheimer’s, stroke, and skilled-nursing care, then her death at age 86; I had pretty much decided that I’d better get things done right now, because I would be decrepit very very soon.

Although I had read drafts of Dancing previously (I wrote one of the cover blurbs), it was wonderful and timely to read it again. Priscilla Long provides us with dozens of models of old creators, not all of them able-bodied, but all—in their 80s, 90s, and 100s—joyously still in the game.

There is so much great stuff here:

Our ageist stereotypes equate old with ill, old with decrepit, old with physical and mental decline. Yet the majority of people over age 85 do not require assistance in daily living and some of these provide assistance. (p. 15)

Long is also a science writer, and her book is meticulously researched. The information about cognitive development (not decline, not maintenance) in old age is something I wish everyone I know would read.

And, speaking of my mother, late in the book, in a section on elegy, Long writes:

Art can provide a shelter, a kind of home, a means of sustenance, for a person in the midst of the shock and sorrow of grief. At the age of 90, the pianist/composer Randolph Hokanson said, “I continue to play because I love music so. It has been the sustaining force in my life. I’d go down the drain without it. It was such a savior after my wife died.”

Is it too obvious to say that one advantage of growing old is to remain alive to the beauty and suffering of the world? To make an elegy is to express that beauty and that suffering. (p. 151)

Thus it has been for me. I love thinking that I will continue to be here (for another 40 years!), reading, witnessing, scribbling—and sharing my work with you.

If you would like to watch the video of my conversation with Priscilla, go to her website: https://www.priscillalong.net

(you can clip past the first six minutes).

May you have an amazing holiday and holiday season. Thank you for spending a few minutes of it with me.

I have kept a journal since I was a teenager. There were earlier abortive attempts, for instance, a Christmas-gift diary with a key when I was eleven or so. Then, in 10th grade, Miss Caughey (pronounced Coy) assigned her students to keep a journal. We may have been reading Anne Frank.

I have kept a journal since I was a teenager. There were earlier abortive attempts, for instance, a Christmas-gift diary with a key when I was eleven or so. Then, in 10th grade, Miss Caughey (pronounced Coy) assigned her students to keep a journal. We may have been reading Anne Frank. filled 35 of them. Just this morning, I began the 36th, the last one I have on hand. I checked the online catalog and though they used to cost a reasonable $18.95, they are now priced $31.90. All paper supplies have gone up lately, my friend reminded me. These are handsome books with lined pages, 400 pages, plus index pages.The quality of their paper allows for double-sided writing (cheaper notebooks, not so much), so they are probably still worth it.

filled 35 of them. Just this morning, I began the 36th, the last one I have on hand. I checked the online catalog and though they used to cost a reasonable $18.95, they are now priced $31.90. All paper supplies have gone up lately, my friend reminded me. These are handsome books with lined pages, 400 pages, plus index pages.The quality of their paper allows for double-sided writing (cheaper notebooks, not so much), so they are probably still worth it.

last question:

last question: