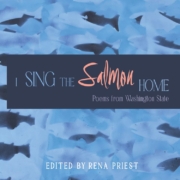

I Sing the Salmon Home

I SING THE SALMON HOME: POEMS FROM WASHINGTON STATE, edited by Rena Priest. Empty Bowl Press, Chimacum, Washington, 2023, 275 pages, $20 paper, www.emptybowl.org.

I don’t believe in magic. I believe in the sun and the stars, the water, the tides, the floods, the owls, the hawks flying, the river running, the wind talking. They’re measurements. They tell us how healthy things are. How healthy we are. Because we and they are the same. That’s what I believe in. Those who learn to listen to the world that sustains them can hear the message brought forth by salmon.

—Billy Frank Jr. (epigraph to I Sing the Salmon Home)

Yesterday’s mail brought this delightful compendium stuffed with salmon poems. Editor Rena Priest (our current  Washington State Poet Laureate) has selected 167 poems as varied as wild salmon themselves. The section titles give us a clue to the contents: “Wild, Sacred,” “Sojourn,” “Invisible Thread,” “Fish School,” “Gratitude,” “Choices,” “Vigil,” “What We Owe.” With a preface from Priest herself, and an introduction by Empty Bowl co-publisher Holly Hughes, this anthology is truly a gift.

Washington State Poet Laureate) has selected 167 poems as varied as wild salmon themselves. The section titles give us a clue to the contents: “Wild, Sacred,” “Sojourn,” “Invisible Thread,” “Fish School,” “Gratitude,” “Choices,” “Vigil,” “What We Owe.” With a preface from Priest herself, and an introduction by Empty Bowl co-publisher Holly Hughes, this anthology is truly a gift.

In the preface (a rich compendium, itself), Priest outlines “the life cycle of this anthology,” and continues:

I am a Lhaq’temish woman—a member of the Lummi Nation. We are salmon people. Lummi is a fishing culture. We invented the reef net—an innovative technology dating back more than ten thousand years….In the cosmology of the reef net, the net symbolizes a womb, and the salmon are the sacred spark of life that will carry the people into another cycle. (xiv)

In the net of this collection, there is so much bounty. This, for instance, the title poem, fittingly by Andrew Shattuck McBride: [note: the last line of each stanza should be indented; if anyone knows how I fix that, please let me know!]

Winter Run, Whatcom Creek

A close friend says she had a fabulous salmon dinner

prepared by her daughter’s spouse. I have questions, ask,

“What kind of salmon?” She smiles. “The good kind.”

I cheer the salmon on.I am not of this place, forego eating salmon. Others—my

sisters and brothers, and orcas—must have salmon to survive,

to renew their lives, their compact with these lands and waters.

I too sing the salmon home.By choice I have no permit or pole or lure.

I receive sustenance from watching the lean clocks

of salmons’ bodies pushing against creek waters.

I cheer the salmon on.Lines and color-infused lures hang entangled in trees’ branches.

A beefy, youngish man with a careful blank expression

sits on a bench. His young do, leashed, lolls nearby.

Beyond, on bloodied grass, two salmon pant

I sing the salmon home.I have questions, decide finally not to ask. What do I know?

This: Along a short stretch of creek just below the noisy falls,

salmon—so close to home—swim a gauntlet. And this;

Salmon strive to live till they spawn.

I cheer the salmon on.—Andrew Shattuck McBride

You know McBride’s name as he was one editor of the recent anthology, For Love of Orcas, from Wandering Aengus Press, and he was one of the people who encouraged Priest to do this book.

I Sing the Salmon Home contains so much lush detail, so much praise, so many ripples of words: “sweet water, sun-flecked, flung skyward” (Joanna Thomas); “tease apart the iridescent / infinite in every scale” (Shankar Narayan); “Salmon running the Sultan // River in a long silver link chain with / amethyst and ruby cabochon eggs” (Laura Da’); “Between sparse old shoreland spruce / the moon is a silver wing” (Robert Sund). With 167 poems and poets to choose from, all I can say is that making choices for this review was not easy.

And, yes, lots of poems about eating—and blessing—salmon, or, perhaps I should say, how the salmon blesses and nourishes us. So, one more short poem, this one written as a “nondominational blessing for meals and gatherings” (as we might consider this entire collection):

Water by Salmon

As life is taught by death,

and the Sun by Space,

so Clouds are taught by Land

and Rains by Place.As Mountains are taught by Plains,

and Rivers by Lakes,

so Trees are taught by Soils,

and Elements by their Weight.As Deserts are taught by Shores,

and Ocean Waves by Wind,

so Depth is taught by Height,

and Tides by Celestial Spin.As Sound is taught by Silence,

and Insight by Reason,

so humans are taught by Water

and Water by Salmon.—Phelps McIlvaine

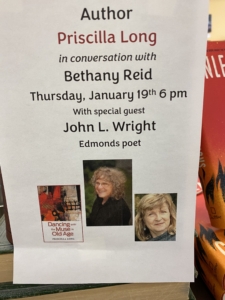

I hope I’ve inspired you to want to hold this book in your hands. It will be in public libraries, as well as available from Empty Bowl Press’s website and your favorite independent bookstore.

And, yes, it is National Poetry Month, and what better month to be reading a poetry book-a-day? If you’re curious, you can skate back to my earlier Aprils (as I’ve been doing these poetry-book-a-day blog posts for a few years now). I also want to apprise you of the August poetry book challenge, which you can read about here—https://www.thesealeychallenge.com/—or here, at Kathleen Kirk’s blog—https://kathleenkirkpoetry.blogspot.com/2022/08/mathematics-for-ladies.html (or at ANY of her August blogposts).

minutes.

minutes. I woke up one night — from a dream? into a memory? — of sitting in the hayfield beside our barn, and watching a foal die. (“A” foal? The foal, Brandy’s foal.) I experienced exactly what Bessel Van Der Kolk describes in his book,

I woke up one night — from a dream? into a memory? — of sitting in the hayfield beside our barn, and watching a foal die. (“A” foal? The foal, Brandy’s foal.) I experienced exactly what Bessel Van Der Kolk describes in his book,

Linda Pastan just put out a new and selected poems, Almost an Elegy, at age 90. A great website for you to investigate further is

Linda Pastan just put out a new and selected poems, Almost an Elegy, at age 90. A great website for you to investigate further is