Elder Voices

ELDER VOICES: WISTFUL, WONDERING, WISE, Editors Marie Eaton, Carla Shafer, and Angela Boyle. Elder Voices  Project, Bellingham, Washington.

Project, Bellingham, Washington.

This anthology collects poems and essays from elders living in Whatcom County, Washington. The launch featured six writers, ending with 100-year-old essayist, Maggie Weisberg, who charmed all of us by announcing, before reading “On Being Old,” that the 70- and 80-year-olds in the audience could be her children.

It’s a cornucopia of delights, calling forth memories of childhood and loved ones long gone, embracing the natural world of years back, and the natural world still left to us, looking forward to new adventures. These are not people taking up their rocking chairs. They’re still growing, changing, writing.

Age Is Relative

Still kicking at sixty-nine years old,

one year short of Dad’s death,

four years past older Sister’s passing,

peering toward Mom’s eight,

astonished by Aunt’s ninety-three,

and still searching for

some sort of meaning

after all these years.— Nancy Kay Peterson

If I had to sum up the book in one word? “Celebration.”

Old Growth

When two old friends stand together

in the forest for six hundred years and

feel the rain prickle against their shredding

bark, feel the heat of the morning press

into their needles on sloping limbs, feel

their silent lives raised from the forest floor

in a flow of phloem and xylem, we pass by

mindful of their presence, as if we mattered

and they rose in service to us — their shade,

their fibers, even their core (where friendship

lives) — sawn through and framed to form

our rooms. Or, mindful of our significance

as less than theirs, walking beneath the canopy

we would kneel, learn the pattern

of their breathing, feel the rain

dampen our sweaters, absorb

the heat of enduring friendship.— Carla Shafer

Chock-full of inspiration, it’s a project I hope to see duplicated elsewhere. You can find a copy at Village Books, located in Fairhaven, and on-line.

front — I’m lowering thresholds all over the place. Soon I’ll be lying inert in the doorway and you’ll have to step over me. But not today! Today, we get a poem from Seattle poet, editor, and teacher Susan Rich.

front — I’m lowering thresholds all over the place. Soon I’ll be lying inert in the doorway and you’ll have to step over me. But not today! Today, we get a poem from Seattle poet, editor, and teacher Susan Rich.

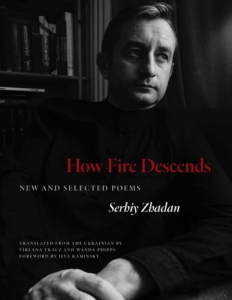

Phipps, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2023, 136 pages, paper, $18,

Phipps, Yale University Press, New Haven & London, 2023, 136 pages, paper, $18,

lesson that our poems might teach others.

lesson that our poems might teach others.