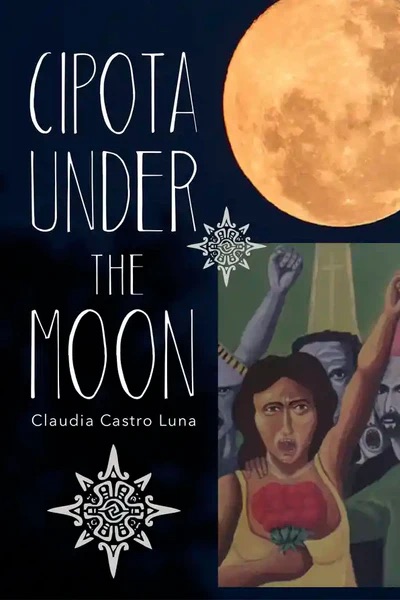

CIPOTA UNDER THE MOON, Claudia Castro Luna. Tia Chucha Press, PO Box 328, San Fernando, CA 91341, 2022, 118 pages, $19.95 paper, www.tiachucha.org.

I blogged about Claudia Castro Luna’s This City, in 2020, while she was still Washington Poet Laureate. This year I  meant to read and write a post about her book, Killing Marías: A Poem for Multiple Voices. Instead I came across her 2022 book, Cipota under the Moon, and I am so astonished by it I hardly know what to say. It is a heart-breaking, multi-lingual full-immersion experience in El Salvador—war, exile, and return. In “This Is Not a Poem,” Castro Luna begins, “Guerra doesn’t go away when the bullets stop, when the grenades go silent, when helicopters’ blades no longer kick up…,” and ends: “I highly don’t recommend it.”

meant to read and write a post about her book, Killing Marías: A Poem for Multiple Voices. Instead I came across her 2022 book, Cipota under the Moon, and I am so astonished by it I hardly know what to say. It is a heart-breaking, multi-lingual full-immersion experience in El Salvador—war, exile, and return. In “This Is Not a Poem,” Castro Luna begins, “Guerra doesn’t go away when the bullets stop, when the grenades go silent, when helicopters’ blades no longer kick up…,” and ends: “I highly don’t recommend it.”

I highly recommend this book.

In the early minutes of her Ted Talk, Castro Luna talks about her family’s journey, and the amazing human ability to heal from trauma.

At the Tia Chucha Press website, I found this description:

In Cipota under the Moon, Claudia Castro Luna scores a series of poems as an ode to the Salvadoran immigrant experience in the United States. The poems are wrought with memories of the 1980s civil war and rich with observations from recent returns to her native country. Castro Luna draws a parallel between the ruthlessness of the war and the violence endured by communities of color in US cities; she shows how children are often the silent, unseen victims of state-sanctioned and urban violence. In lush prose poems, musical tankas, and free verse, Castro Luna affirms that the desire for light and life outweighs the darkness of poverty, violence, and war. Cipota under the Moonis a testament to the men, women, and children who bet on life at all costs and now make their home in another language, in another place, which they, by their presence, change every day.

Here’s an example form the poems before immigration:

Garrison

Two girls slinked alongside barb-wired brick walls on their way to swimming lessons, doing their best to remain collected past the turrets stationed with armed soldiers. Ensconced in their look-outs, the troopers held their metralletas close to their bodies, as if they loved them, but not so much they would not use them ill. After our lesson, we headed home the same way we walked to the pool, guillotining chatter and laughter, scurrying along the garrison’s walls. Only the sound of our flip-flops striking our heels betrayed us. What if today’s soldiers were in a foul mood and pulled their triggers? What if they noticed our bulging bags, our weekly comings and goings, and tagged us as informants? What if, right leg, what if, left leg, we got through it that way—like prayers in a rosary—one bead, one foot in front of the other, one bead, one foot, one bead, one foot all the way home.

—Claudia Castro Luna

And here, a poem during and after:

Cloven Moon

The officer in charge of processing my family’s entrance to the U.S. stated that from that moment on my name was to be Claudia Castro. The passport says her name is Claudia Castro Luna, my mother objected. Here we use one last name, said the officer, and closed the matter with the gavel of his voice. Your moon got taken away from you, said my friend when I recounted the story. But when the officer eclipsed the Luna of my name the sensation was more like having a limb chopped off. For years I walked like that, cloven, until pen in hand, I began to weave into blank pages tamales de elote, scent of yerbabuena, spells of flor de muerto, the riot of a Tuesday market in Ahuachapán, the Nahuatl sageness of my abuela. I did not know then that weaving like this, warp of memory, weft of daring, had the power to sew back the name chopped off at an INS center on a January morning in 1981. All I know is that one day I walked into a Social Security office, took a number, and waited my turn to expand the canon of last names in this country. I pilgrimaged the department of motor vehicles, registrars’ offices, bank-teller windows, and once La Luna hung again in the firmament of my name, its light spilled beneath my skin and filtered back into the open mouths of a million pores.

—Claudia Castro Luna

Most of the poems are prose poem. A few are in El Salvadoran Spanish. Even the poems reaching back to the Eden of early childhood seem tainted, overshadowed by war. On every page, I was struck by the metaphors. “the sulphur reek of his step” (“Shade Grown”); “Violence spread like tincture inside a water glass” (“El Salvador 1980”); in a long poem, “Dios Madre,” these lines, “Cupped in his hands / his ten-year-old daughter / in her school uniform / passed from smiling / to hardened concrete.”

I hope you will further explore Castro Luna’s work on your own. Here is a review: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/harriet-books/reviews/157890/cipota-under-the-moon

And here, a link to a one-hour interview and reading from Cipota under the Moon:https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?ref=watch_permalink&v=5205831112787187.

A MAN WITH A RAKE, Ted Kooser. Pulley Press (an imprint of Clyde Hill Publishing), Seattle / Washington D. C., 2022, 32 pages, $14 paper, https://www.clydehillpublishing.com/pulleypress.

A MAN WITH A RAKE, Ted Kooser. Pulley Press (an imprint of Clyde Hill Publishing), Seattle / Washington D. C., 2022, 32 pages, $14 paper, https://www.clydehillpublishing.com/pulleypress. Beginning Poets ought to already be in your home library. (Even if you’re not a poet.) He is a former United States Poet Laureate, won a Pulitzer Prize for Delights and Shadows, etc. Anytime I’m told, “if you lived back east, you’d be better connected,” I think of Kooser, living in the midwest, writing about farms and farmers and farmhouses, working as an insurance agent for much of his career (!), and still here, still writing.

Beginning Poets ought to already be in your home library. (Even if you’re not a poet.) He is a former United States Poet Laureate, won a Pulitzer Prize for Delights and Shadows, etc. Anytime I’m told, “if you lived back east, you’d be better connected,” I think of Kooser, living in the midwest, writing about farms and farmers and farmhouses, working as an insurance agent for much of his career (!), and still here, still writing.

meant to read and write a post about her book, Killing Marías: A Poem for Multiple Voices. Instead I came across her 2022 book, Cipota under the Moon, and I am so astonished by it I hardly know what to say. It is a heart-breaking, multi-lingual full-immersion experience in El Salvador—war, exile, and return. In “This Is Not a Poem,” Castro Luna begins, “Guerra doesn’t go away when the bullets stop, when the grenades go silent, when helicopters’ blades no longer kick up…,” and ends: “I highly don’t recommend it.”

meant to read and write a post about her book, Killing Marías: A Poem for Multiple Voices. Instead I came across her 2022 book, Cipota under the Moon, and I am so astonished by it I hardly know what to say. It is a heart-breaking, multi-lingual full-immersion experience in El Salvador—war, exile, and return. In “This Is Not a Poem,” Castro Luna begins, “Guerra doesn’t go away when the bullets stop, when the grenades go silent, when helicopters’ blades no longer kick up…,” and ends: “I highly don’t recommend it.”

to both praise, and make sense of the world.” “Making the ordinary extraordinary” is how I would put it. Familiar territory, at times: Scotch broom, pickup trucks, a father’s war stories, wasps, “horse on a rope in the fog.” But also Van Gogh, Dante, Gorky. This is quintessential Germain, twining her themes together, making a whole that is both fragmentary and lush.

to both praise, and make sense of the world.” “Making the ordinary extraordinary” is how I would put it. Familiar territory, at times: Scotch broom, pickup trucks, a father’s war stories, wasps, “horse on a rope in the fog.” But also Van Gogh, Dante, Gorky. This is quintessential Germain, twining her themes together, making a whole that is both fragmentary and lush.

85 pages, $18 paper, www.middlecreekpublishing.com.

85 pages, $18 paper, www.middlecreekpublishing.com.