My dear friend Carla Shafer is retiring from her job as a grant-writer at Everett Community College. (Click on her name to find an interview.)

My dear friend Carla Shafer is retiring from her job as a grant-writer at Everett Community College. (Click on her name to find an interview.)

Yesterday was the retirement party and today is the poetry reading. You kind of have to know Carla to understand why retirement = poetry reading. But I will be there, along with a few other poets, to read and pay tribute to this amazing person. Two o’clock, Russell Day Gallery, if you are interested. (Come early! It will be crowded!)

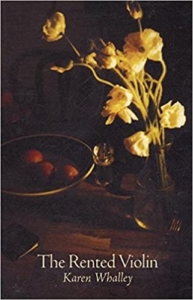

This poem is from an early collection of Carla’s, titled Rain Song, which William Stafford called, “a rich array…so sweet…so warm…and onward.” I have at least a dozen other favorites to choose from, but this one strikes me as a tribute-poem, through and through.

TEN GOOD LINES

Rilke says to wait to write the poem.

Experience must pile up like laundry.

Later picked through, it will relinquish

maybe 10 good lines. Worthy of one’s life time.

Once I watched William Stafford construct

a poem. Early in the day he planted seeds —

“…a picnic on the beach, a campfire in the sand.

You bring your violin, I heard we have a banjo player…

come…sometimes people choose to sing.”

Under a cool summer sky, kicking sand,

we gathered around the fire.

Bill was there early and stayed until the end,

collecting the scene’s pieces and

sensing careful phrases. The next day

he shared ten good lines.

So I thank Rilke for telling me that

I might spend my life to reap

a meager, but worthy, feast.

And I thank Stafford, who lives

each minute as a source for poems

cooked and served up daily.

So many poets, so little time. I barely dented my book collection, and left out so many other favorites. Next year, thirty more?

So many poets, so little time. I barely dented my book collection, and left out so many other favorites. Next year, thirty more? My dear friend

My dear friend